As America enjoyed the glories of a postwar boom, what had been a serious, hardworking nation began a radical transfiguration. The characteristic sobriety was fading, the center of gravity shifting away from New England and New York to the dream world of California. By 1955 America could feel pride in a young coterie of writers and artists it might finally call its own. Would anyone ever mistake Jack Kerouac, William Burroughs or Elvis Presley for Europeans? It was the year Disneyland opened.

Jackson Pollock inaugurated the first genuinely American art and it was a lot more about the gesture, the act of creation, than the finished product. The American penchant for action was combined with intellectual knowingness. What was to happen on the canvas was not a picture but an act. The painter had become an actor, and in this transformation the usual catching up with European art forms came to a halt. Americans were playing by a different set of rules. The new idea of pure freedom, the movement toward a life free of every natural constraint was first announced in those feverish years. Today Americans are both grappling with the consequences of hyper freedom and working toward making it the core operating principle of our public lives. I would argue this is a revealing lens through which to view the upcoming election — and likewise the country’s tumultuous response to the coronavirus.

American politics and American business have never completed that revolution, but they have also never ceased approaching the ideal point where they are indistinguishable from Hollywood. Reagan said that politics was just like show business. He came from Hollywood and understood better than anyone that the country’s life needed new myths. He often explained to his interlocutors that he would never understand how anyone could be president without having first been an actor. It is an interesting sentence, even if Reagan did not mean it in full seriousness. On some obvious level though, he did mean it. Movies were a source of endless material for speeches and impromptu comments. Some of Reagan’s most inspired moments happened once he let his prodigious memory of cinema quotes dictate what he said. Movies give you emotional intelligence and prepare you for crises. After all, every movie is about a crisis of some kind. He loved War Games, in which a teenage hacker — becoming confused between a simulation and reality — inadvertently triggers a nuclear war, then saves the world, and was impressed by Firefox, in which Clint Eastwood is recruited to steal a Soviet fighter jet controlled by telepathy. Because the Cold War never came to a hot climax, Americans were left with stories like these as the main, or at least familiar, narrative of their triumph over the Soviet Union.

After his movie career was effectively over, Reagan starred in what was television’s first reality show, opening his new ranch-style house to the public in order to exhibit all the latest domestic gadgets with which General Electric had equipped it. The nightly reel made him an instant celebrity. Unknown to the viewers, it would eventually make him president.

What Reagan opposed was the increasingly exhausted logic of pure liberalism, under which life choices and experiences are all subjected to a litmus test of universal validity. And while liberalism neutralizes many of the dangers societies and individuals had been living with for millennia, it does so at the enormous cost of preventing people from enjoying freedom to the fullest.

Reagan wanted Americans to live more like movie characters, lost in many different identities and relaxed about their ultimate truth or meaning. Many have noticed that his critical ideological tenets had a certain levity, even frivolity. He never followed through with what the religious right interpreted as specific promises on abortion and other matters. He never reduced the size of the welfare state or reformed social security. But was Reagan even interested in material changes of this kind? He succeeded without them by endowing the personal mythologies of business and family with the same power of those translucent images which the moviegoer replays in his mind as he leaves the theater, holding the promise of a more exciting and more beautiful life.

To say that Reagan’s policies were contradictory — that, for example, they tried to promote traditional values while unfettering forms of financial capitalism that were ill at ease with a traditional way of life — is to miss the point. They were as contradictory as two Hollywood movies in which the same actor might present different and opposite human types. All human possibilities may be simultaneously pursued in a politics governed more by imagination than by reality. None can claim a special status. None is true if by true we mean that every other alternative would be false. They are equally interesting and equally worth pursuing. As Jules Feiffer once said, when addressing Reagan’s defense of religious creationism: “If Reagan had played Darwin in a movie, he would believe in evolution.” The possibilities of the political virtualism he helped create are essentially endless.

My hypothesis — the subject of my new book, History Has Begun — is that American life continuously emphasizes its own artificiality in a way that leads participants to believe that they are living a fantasy. Americans are learning to live in a realm of hyper freedom, possessing the power to create imaginary worlds and the freedom to unleash a kind of selfish and extravagant fantasy life. Americans no longer ask whether a book or television series would work in real life, they ask whether real life would work in a movie or television series.

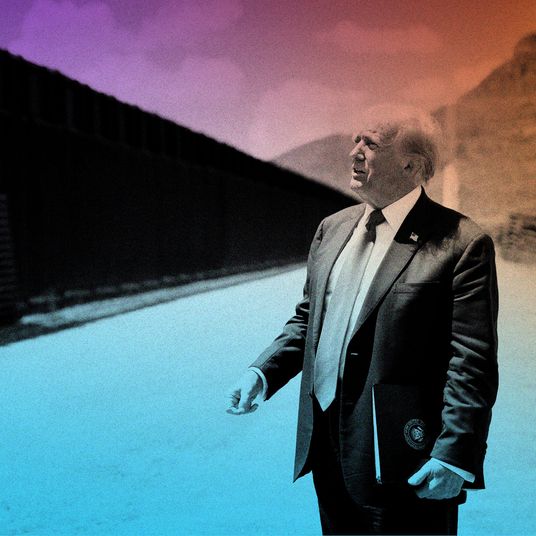

Donald Trump so epitomizes this latest phase of American hyper freedom that it fundamentally misses the point to compare his political career to that of any other celebrity or entertainer in the past who entered the arena of politics. Even Reagan used his fame and the techniques of entertainment to appear a more genuine and more appealing politician than his rivals. Trump is the exact opposite. He does not use the tricks of entertainment to appear a better politician, he uses politics as a better stage for his performance as an entertainer — a paradigm shift, a Copernican turn. When asked if he would accept the results of the election, Trump ended the final presidential debate with a classic cliffhanger: “I will keep you in suspense.” Discussing possible sanctions against Turkey, he tweeted in October 2019: “Treasury is ready to go, additional legislation may be sought. There is great consensus on this. Turkey has asked that it not be done. Stay tuned!” More dramatically, he explained during a rally in Minneapolis the same month: “That was one of the greatest nights in the history of television. It was one of the highest rated evenings in the history of television.” As Jonathan Chait commented in amazement: “The president of the United States thinks of his own election as a show that he watched on TV.” Perhaps even more amazingly, a striking number of Americans also seem to regard politics as a realm of pure theater — giving Donald Trump almost precisely the same marks this fall, with almost 200,000 dead, a historic economic contraction, and the most significant racial unrest in a generation, as he had a year ago. Or four, when he took office.

In an obvious way, the pandemic provided a perfect season-ending climax to the story of Trump’s first term. A country built on the promise of fantasy was now facing reality in its purest form: Viruses are not even properly alive, being closer to biological chemicals. How would America react? Would its flight from reality come to a premature end? Six months in, what is most striking is how little has changed.

While in China or Europe the new coronavirus was regarded as a technical problem to be solved, in America it quickly became part of a dramatic narrative. The country seemed to take its cues from movies such as Contagion: the president insisting that nothing is wrong while events on the screen show otherwise, the race against the clock to avert catastrophe, the conflicts between the main characters. Comparing the reaction in the United States to that in other countries, what strikes me is how the physical virus is almost eclipsed by the collision of narratives. The attention is so often on what the different characters think, say and do. The plot tension is central: For instance, will Trump approve a vaccine against all scientific advice? Just like in a disaster movie or television series, the epidemic is a backdrop for action.

The protests and counterprotests provide another seeming counterargument: What could be more “real” than the matter of justice and police violence? But while the political drama that began in Minneapolis in May — and continues today not just in Portland and Kenosha but all around the country in less-noticed places — feels undeniably large and consequential, strikingly little appears actually at stake. Police abolition is a political nonstarter, and defunding the police not much more popular or viable. Even qualified immunity seems likely to endure. The country’s most liberal mayors seem unable to enact meaningful reform, and the city’s most progressive police departments are not inclined to even boast of their achievements — believe it or not, the NYPD is exemplary both in terms of crime reduction and violence against citizens, but prefers to fight a culture war and threaten the return of the 1970s. And while racial progressivism has drawn many more white professionals to protests, both real and virtual, than ever before, polls show few of them support meaningful reforms of housing or school policies, which are the basic obstacles to reducing racial inequalities in this country. Instead, they apparently prefer to read Robin DiAngelo and reflect on their own sins.

When modern societies purged themselves of religious piety and autocratic politics, they chose to sacrifice some of what makes life interesting in order to prevent the worst. Better to live in Switzerland, a nation tamed by liberalism, than in Russia or Iran, which are not. But maybe it is in contemporary America that we see the next phase beyond liberalism. The United States has developed a culture of ceaselessly depicting its own collapse in gripping fictions: superhero movies, and movies of disaster both natural and man-made. The depictions are not intended to be fully real, of course — the horror of watching New York City destroyed in a cinematic fantasy is different than the horror of watching it destroyed in reality. Perhaps America’s current political travails may be seen as the next evolution in the culture that gave us The Day After Tomorrow. As engrossing as our present political battles are, perhaps they are not completely real? I would argue that America is not poised to become a place like Russia or Iran, but rather is mirroring a television show about a place becoming like Russia or Iran. This is the genius of the new America. Trump offered Americans the virtual experience of a nationalist regime without its more dire real-world consequences. The woke left is playing a different variety of the same game, giving Portland — but also the rest of the country — the virtual experience of a revolutionary regime. It is a politics where imagination outstrips reality.

In this way, Trump and the elements of the left that are creating — or enabling — chaos in cities like Kenosha, Seattle, and Portland have something in common: They are equally expert at inventing characters and acting out various fictional scenarios in real life. And while some of these conflicts have produced very real injuries and even deaths, they remain almost allegorical to most Americans. The images may be shocking and spectacular — at some level they are required to be by the logic of this new politics — but the immersive experience of an authoritarian regime or a cultural revolution is of course very different from the real thing.

America seems to be testing whether as a society it might be organized around the two key principles of virtual reality. First, the experience must be immersive. Doubt and skepticism have a role in human society, but they cannot sustainably be present everywhere. Second, a way to stop the game or experience. Like malware authors, we need a kill switch in case we lose control over our own creations — in case things get too real. Provided this switch is available, the game itself may well be dangerous or offensive.

The immersiveness of America’s politics can’t be in doubt — but what about a way to change or stop the action if things get too dangerous? That question is harder, though clearly my hypothesis depends on some form of self-regulation inside the system that always guides the collective virtual experience away from real-world catastrophe. Elections can play a role in this — but, as with this one, can also be climactic events inside the fantasy. Courts can also be a down regulator. The press should be able to play this sort of role. But the ultimate goal is not to break through the illusion and bring people back to reality — rather the reverse. We want to keep social life at the fantasy level and prevent particular fantasies from being imposed on others as something real, something from which there is no escape. Never get caught in the dreams of others.

It is true that contemporary America is leaving liberalism behind, but that is because this society detected a fatal flaw with the liberal project: In liberals’ attempt to free us from every political danger, they offered us a society without depth, and a human world with no real wealth of experience. What Americans since Reagan have realized is that there is a third way between radical politics and liberalism. Decline? Collapse? No — rather, to live a virtual public life created around representations of extreme politics existing in other countries or other historical periods, but experienced in relative safety.

Today the proposition that the whole planet is on course to embrace Western liberalism is no longer credible. One would expect the only global superpower to acquire a level of distance from those ideas or, at least, to reexamine them in full and even contemplate how they can be revised and improved. And in fact what we see in America today is a serious engagement with the most serious questions of modern political history. Whether the adventure will come to a happy end is perhaps too early to tell, but American political life is busy with big, daunting problems. The problem of freedom first of all — America is battling with hyper freedom — but also the question of how to reconcile a greater depth of experience than is possible in a liberal society with the freedom from authoritarian rule promised by liberalism. Conventional wisdom suggests that the United States has already reached its peak. But what if it is only now starting to forge its own path forward? What if American history is only just beginning?

This is an adapted excerpt of History Has Begun, published by Oxford in September.