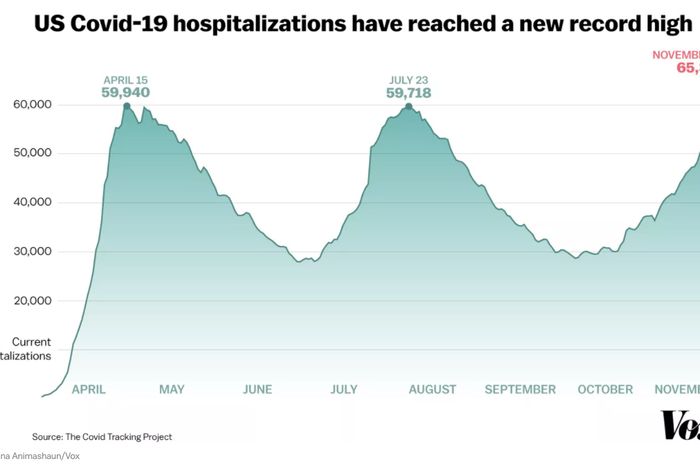

The number of Americans hospitalized with COVID-19 is higher now that it has ever been. The seven-day moving average of confirmed cases in the United States is 40,444 cases higher today than it was one week ago. Hospital systems in several states are under severe stress. Utah and North Dakota have begun to exhaust their limited capacity of hospital beds.

And winter has not even begun.

Barring some great good fortune — or the rapid dissemination of a working vaccine — the next few months could be the most difficult of the pandemic thus far for the U.S. writ large. Across the northern hemisphere, the not-so-novel coronavirus is exhibiting clear signs of seasonality. The bug seems to spread more easily in cold dry air and when humans are huddled indoors, sharing spaces with limited ventilation.

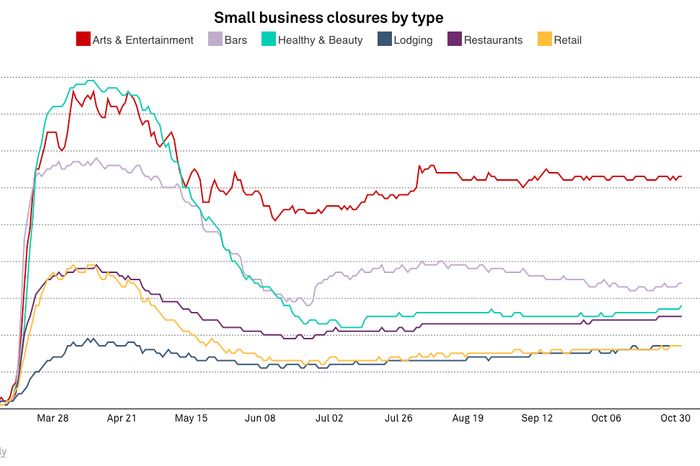

Meanwhile, winter is also shattering the fragile accommodations that many small businesses have made to the pandemic. Summer offered restaurants and bars relatively comfortable and safe conditions for serving their customers (when the rain was at bay). And by keeping case growth within certain regional and epidemiological bounds, the warmer months also enabled businesses in many fortunate areas — those with high levels of public-health skepticism and low levels of infection — to operate at something approximating normal capacity. This said, even during a favorable season — and before the CARES Act’s direct and indirect supports for small businesses were depleted — tens of thousands of firms closed their doors.

The sane response to this state of affairs was, oddly enough, articulated by someone in proximity to presidential power on Wednesday. Dr. Michael Osterholm, a pandemic adviser to President-elect Joe Biden, suggested that Congress could establish open-ended wage and revenue replacement for workers, firms, and sub-federal governments for four to six weeks — during which the nation could enter a unified lockdown of nonessential businesses. Implemented correctly, this could flatten the curve of infection, saving untold lives while keeping Americans financially stable. These measures would make sense if we didn’t appear to be only months away from a widely available vaccine. With a path to vaccine-induced herd immunity in sight, it is obscene for our society to acquiesce to mass death.

Alas, our society has a thing for such obscene acquiescence. Osterholm’s approach looks impossible in a country as demented and divided as our own. But as our COVID winter darkens, the outlook for a robust stimulus package just might brighten.

Most of my analysis on the prospects for another round of COVID relief has been premised on the assumption that — if Republicans retain control of the Senate — the next round of stimulus will be either meager or non-existent. After all, if Mitch McConnell was unwilling to meet Democrats halfway earlier this year (when reaching a deal would have been a political boon to a Republican president as well as the most vulnerable members of his own caucus), why on earth would he do so now (when reaching a deal would be a political boon to Joe Biden)? The Senate Majority Leader’s core strategic insight during the Obama years was that the American people hold the president’s party responsible for conditions in the country and legislative failures on Capitol Hill. Thus, if an opposition party secures control of one chamber of Congress, it can increase its odds of winning back power in ensuing elections by obstructing the president’s agenda and/or sabotaging the economy. Under Barack Obama, Mitch McConnell’s caucus agitated for spending cuts when unemployment remained near double digits; under Donald Trump, it embraced deficit spending when unemployment was near historic lows.

But I’m not sure if the congressional GOP ever allowed itself to comprehend what this winter was liable to look like. Already, Republicans have made half-hearted efforts to pass further relief for small-business owners, who comprise a significant portion of the party’s activist and donor base. McConnell held a vote on a $500 billion relief package that would have renewed funding for the Paycheck Protection Program. As the coronavirus digs deeper and more durably into deep red areas of the country, and winter makes it even more difficult for many small service-sector firms to survive, it’s not clear whether the GOP will be able to withstand internal pressure to actually deliver substantive aid to one of its core constituencies.

Which is to say: There’s a good chance that, eventually, McConnell will feel that he needs to make a deal. And he may well prefer to make it during the lame-duck session, when Biden will reap less credit for the legislation (even if the new president enjoys some benefit for its effects).

Of course, small business has a major presence within the Democratic coalition too. And so it is possible that all of the factors cited above will break House Democrats’ will and force them to acquiesce to McConnell’s terms on relief. But the Democratic Party’s main sticking point in previous negotiations — their insistence on massive fiscal aid to states and municipalities — will only look more reasonable as local governments across the country hemorrhage tax revenue. The end product is almost certain to be too little, too late. But given enough death and bankruptcy, Republicans might be forced to back the kind of robust relief package they refused to put on Trump’s desk when they had the chance.