At various points in human history, pandemics have served as “great levelers.” The bubonic plague was indifferent to the narcissism of humanity’s small differences, tearing the life from landlords and peasants alike, while leaving the surviving commoners with more economic power over their social superiors than ever before.

COVID-19 is no such scourge. Far from bringing equal-opportunity immiseration, the present pandemic has concentrated the bulk of its wrath on largely disempowered minorities of the population — the elderly, infirm, incarcerated, and hyperexploited — while our response to the virus has turbocharged America’s (already neo-feudal level of) economic inequality.

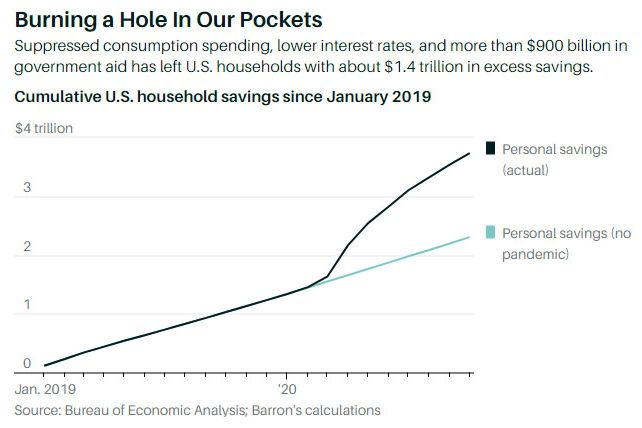

Recessions almost always afflict the afflicted more than the comfortable. For vulnerable workers, downturns mean indefinite losses of income and social dislocation; for the well-heeled, they mean an opportunity to reap windfall returns by buying up temporarily depreciated assets. Yet even by the standards of past recessions, the COVID crisis has produced a wildly inegalitarian distribution of economic pain. The vast majority of U.S. workers did not lose their jobs during the pandemic, but did receive an unexpected $1,200 payment from the government. Meanwhile, thanks to the CARES Act’s UI provisions, many temporarily furloughed workers ended up with more income than they would have earned absent their brief bouts of unemployment. These realities — combined with a pandemic-induced contraction in consumption opportunities and rallies in the stock and housing markets — have left a majority of U.S. households in better financial shape than they were before the crisis started.

At the same time, a large minority of Americans have faced economic misery. Small business owners who failed to secure PPP funds have had their livelihoods destroyed. The long-term unemployed, who were not eligible for UI benefits, got little beyond a $1,200 check to see them through the labor market’s collapse (if they even got that). Other workers struggled to make it through the tangled thickets of state unemployment-office bureaucracies to secure their benefits, or saw their federal aid expire long before their industries recovered. As a result, as many as one in six Americans (including one in four U.S. children) are poised to suffer food insecurity by the end of the year — a 50 percent increase over 2019 — while 14 million households are at risk of eviction.

In this context, there are much better ways to allocate an additional $460 billion in relief funds than sending $2,000 checks to virtually every household in the country. By some estimates, the House’s newly passed bill — which would increase the size of the next round of stimulus payments from $600 per individual to $2,000 — would deliver cash assistance to 94 percent of households. A family of five with an annual income of $350,000 — which has seen the value of its house and 401(k)s rise over the course of this year — would receive a portion of relief funds. If it were possible for Congress to use $460 billion to provide monthly $2,000 checks to every financially embattled household, instead of giving an equal amount of aid to financially comfortable middle-class families and indigent ones, there would be nothing progressive about demanding the latter over the former.

But that is not possible. And so liberal critics of $2,000 stimulus checks need to get realistic and stop letting the perfect be the enemy of the good.

In recent days, Democratic economist Larry Summers, Washington Post columnist Catherine Rampell, and other center-left policy wonks have spoken out against the $2,000 payments, arguing that it would be better to spend an equivalent sum of money on aid to the needy, higher unemployment benefits, and/or fiscal aid to states and cities. A few years ago, such arguments would have been premised on a notion of fiscal scarcity; which is to say, on the idea that the U.S. government has very limited capacity to increase deficit spending without generating high inflation, and so a dollar spent on indiscriminate relief checks is a dollar that cannot be spent on increasing more targeted aid. But this view was falling out of fashion before the pandemic. And the persistence of negligible inflation across most advanced economies this year, despite historic levels of deficit spending, has further eroded its power.

Thus, Rampell hangs her argument on the notion that, even if spending is not constrained by fiscal capacity, it is still delimited by politics:

Advocates on the left argue that there is room to do both. But even if you believe that there are no real debt constraints, given how low interest rates are, there are still political constraints. Republicans set a $900 billion cap on relief measures in the final deal, which meant that funding stimulus payments required shortchanging unemployment benefits (and state and local assistance).

This strikes me as exactly wrong. Yes, Republicans placed an arbitrary cap on the sticker price of the latest relief bill. But they also placed an arbitrary prohibition on open-ended fiscal aid to states. One could perhaps argue that it was a mistake for progressives to insist on relief checks during negotiations over the package, as integrating the $600 payments into the legislation was offset by a reduction in the longevity of unemployment benefits. But even if we stipulate that it was progressives — and not Donald Trump — who incited Senate Republicans to prioritize relief payments over more durable aid to the unemployed, this trade-off is not as unreasonable as Rampell suggests.

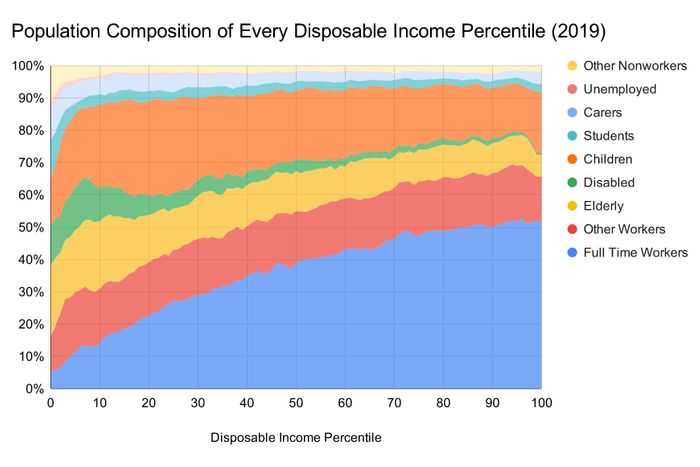

As Matt Bruenig notes, the neediest people in American society are not typically eligible for unemployment benefits, while many recipients of such benefits have considerable wealth and future job prospects (there is no means test that one must pass to access UI benefits). In fact, less than one-third of those in the bottom 10 percent of America’s disposable income distribution are in the labor force; the bulk are elderly people, the disabled, children, and caregivers. Extending the duration of unemployment benefits will not necessarily increase the income of these Americans, but providing them with an extra $1,400 in cash support would spare many from hunger and homelessness.

Regardless, Rampell’s analysis of the political constraints around relief are plainly outdated. Congress is no longer haggling over the composition of a $900 billion relief bill. It is arguing about whether to increase the size of the relief bill by roughly half-a-trillion dollars. The choice is not between spending $460 billion on poorly targeted relief payments or on eradicating poverty. It’s between seizing an opportunity to secure an extra $1,400 for almost every American — including those who desperately need such cash aid — or providing no further assistance for weeks, if not years (depending on the outcome of the Georgia Senate runoff elections).

Of course, there are better ways to allocate $460 billion in additional relief funds. But there is no other way that Donald Trump has demanded — and thus, none that 44 House Republicans would have voted for, or that multiple conservative Republican senators would have endorsed. Kelly Loeffler and David Perdue weren’t about to demand a vote on $400 billion in fiscal aid to states until “the populist left” spoiled everything with their $2,000 check obsession. Congress was about to pat itself on the back for providing $900 billion in total relief when Donald Trump handed Democrats an opening to push for 50 percent more stimulus, and the party took that chance.

Unless one believes that the U.S. is on the brink of runaway inflation, this development seems unambiguously good! When compared with an alternative of “nothing,” adding a half-trillion dollars to U.S. households’ bank accounts actually furthers the very objectives that Rampell and Summers wish to prioritize: providing Americans with more disposable income will surely produce more consumer spending, and thus, more sales-tax revenue for state and local governments to collect, and more job opportunities for the unemployed. Most critically, the measure gets a significant amount of cash into the hands of those Americans who need it most. The U.S. center-left is used to accepting deeply flawed means of providing aid to the needy in deference to political constraints. And the compromises that Larry Summers & Co. have traditionally made in this area are far worse than the deal presently on offer. Previously, Democrats accepted anti-poverty compromises like the EITC at the cost of doing nothing for the neediest; now, they have a chance to secure an anti-poverty bill that covers all of the poor, at the cost of also doing something for the middle class. This is a clear improvement and should be recognized as such. It is better for welfare spending to be inefficient than insufficient.

It is true that if Democrats Jon Ossoff and Raphael Warnock prevail in Georgia’s Senate elections next week, Congress might have the opportunity to allocate $460 billion in relief funds more efficiently when Joe Biden takes office (although it’s unclear why spending that sum on checks today would prevent a unified Democratic government from spending on other priorities tomorrow, given that Democrats voted for a $3 trillion relief package in March). But even if that weren’t an intolerably big if, America’s most vulnerable can’t wait weeks for further cash assistance. And as Rampell herself concedes, “near-universal stimulus payments” can “be distributed more quickly than unemployment benefits,” or any other form of relief.

The columnist dismisses this fact as “more an indictment of our broken unemployment insurance IT system (really systems, since every state and territory has its own) than praise of stimulus payments.” And she is undoubtedly correct that the American welfare state is in desperate need of renovation. Beyond the logistical complexity and shoddiness of our federalized UI system, America’s safety net is aberrantly threadbare. Virtually every other developed country entered the pandemic with vastly more generous unemployment benefits, more comprehensive public health-insurance coverage, and higher child welfare benefits, among other things. America’s fiscal response to the crisis has been quite robust relative to other countries, but this fact largely reflects the costs of mounting a “pop-up welfare state.”

But you go to war (on poverty) with the safety net you have, not the one you might wish to have at a later time. Donald Trump is not about to force Republican senators to support federalizing unemployment insurance. It’s $2,000 checks for almost all, or inadequate aid to the poor. Center-left policy wonks must put pragmatism before ideological purity, and prioritize comforting the afflicted over stiffing the comfortable.