Since summer’s end, the public has chilled on Joe Biden and his agenda.

In mid-August, voters approved of the president by a margin of 50 to 43.8 percent in FiveThirtyEight’s polling average. Today, they disapprove of him by a margin of 51.1 to 43.2 percent.

Biden’s Build Back Better bill — a package of social-welfare programs and climate investments — has fared little better. A new ABC News–Ipsos survey finds that only 25 percent of Americans believe the legislation would “help people like them,” while a 32 percent plurality say it will hurt them. The remaining respondents say they don’t know enough about the president’s top policy priority to have an opinion or else that it will make no difference in their lives. Remarkably, only 47 percent of Democrats in the poll say the Build Back Better agenda would help people like themselves.

Meanwhile, an NBC News poll finds that Republicans now boast a commanding 18-point lead on the question of which party better “handles the economy.” And the GOP’s advantage on inflation is even larger:

Polls of Tuesday’s Virginia gubernatorial election, which put Republican Glenn Youngkin slightly ahead in a state that went for Biden by ten points last November, further testify to the president’s woes.

The critical question for Democrats is whether those woes will prove abiding. The party still has a year to get back into the electorate’s good graces before the 2022 midterms. The feasibility of such a bounce-back depends, in large part, on the source of Biden’s present troubles. If voters have soured on the president out of frustration with his stalled agenda — and/or discontent with economic conditions — then the Democrats have a clear path back to popularity: Pass the Build Back Better and bipartisan infrastructure bills, then hope that inflation declines over the next 12 months (as most experts believe it will), while COVID recedes and job growth accelerates.

But there is another hypothesis, one widely posited among Democratic partisans: that Biden’s woes derive primarily from media distortions, not objective realities. If that analysis is accurate, then it’s less obvious how the party can overcome its present difficulties.

The case for “LOL, nothing (but the media) matters.”

The argument for thinking that Biden’s troubles owe less to political and economic developments than to media coverage is twofold: (1) By many reasonable metrics, the political and economic situation is fairly good, and (2) the media environment is structurally biased against the Democratic Party due to the right-wing media’s strength and the mainstream media’s tendency to drive down approval of the in-power party.

Most analyses of Biden’s plight emphasize two factors: the stagnation of his legislative agenda and the deterioration of economic- and public-health conditions.

Yet there is nothing aberrant about the Democrats’ protracted negotiations over the Build Back Better bill. Donald Trump did not sign his signature tax cut into law until days before Christmas 2017. Barack Obama did not secure the Affordable Care Act’s passage until his administration’s second year. By contrast, Biden already has a $1.9 trillion economic bill under his belt, and Congress appears to be just weeks away from passing the largest investment in green energy in American history, the largest expansion of U.S. public education in a century, permanent unconditional cash assistance to poor families, and a wide array of other new social programs.

Separately, Biden’s signature economic goals are far more popular than those of his immediate predecessors. Unlike Trump, the president is not trying to advance deeply controversial tax cuts for corporations. Unlike Obama, he is not trying to enact systemic reform of the health-care system (historically a politically thankless task). Rather, he has assembled a bunch of largely majoritarian social-welfare programs and tax increases on the superrich.

Beyond the popularity of its individual provisions, the Build Back Better agenda would also increase household income for the bulk of the U.S. population, at least in the immediate term. It is hard for some Democrats to look at that fact — and then at polls showing that only 25 percent of voters think Build Back Better would “help people like them” — and avoid the conclusion that the news media has failed to keep Americans well informed. Another finding in the recent ABC News poll reinforces that impression: Only 31 percent of Americans say they know either “a good amount” or “a great deal” about what’s in Biden’s infrastructure and social-spending bills.

As for the economy, Biden is presiding over one of the most rapid labor-market recoveries from a recession in modern memory. To the majority of Americans who work for a living, the labor market is historically favorable. This reality is reflected in soaring wages (particularly at the bottom of the income spectrum), a sky-high quit rate, several successful strikes, and some public-opinion data: The public’s evaluation of how easy it is to find a job is at a higher point now than it has been at any time since 2000.

Meanwhile, household wealth is at a record high. And although that wealth is extremely unevenly distributed, a majority of Americans appear to have more in savings than they did before the pandemic. Finally, investment in capital goods — long the GOP’s preferred metric for economic health — is at its highest point on record.

Of course, the counterpoint to all this is inflation. Although nominal wage growth is high, rising prices have pushed real wages down for the top three-quarters of workers through most of this year.

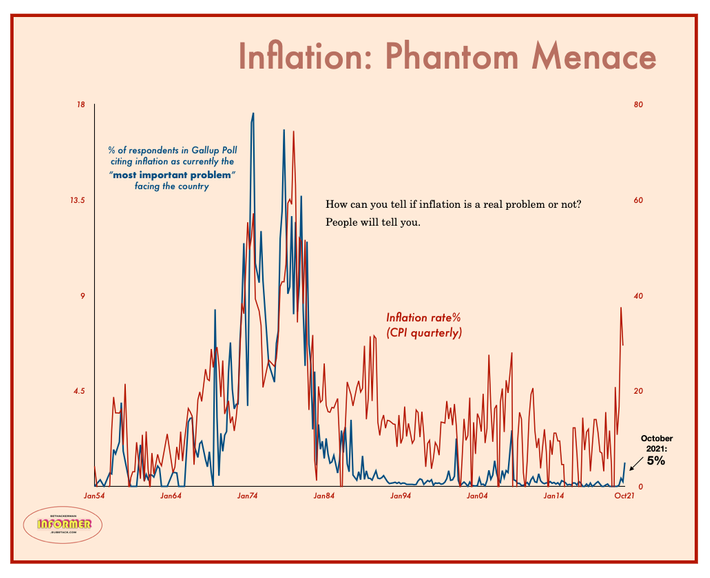

And yet during the third quarter of 2021, when Biden’s approval began falling, real wages actually rose. What’s more, as the socialist commentator Seth Ackerman notes, neither inflation nor public concern about inflation is especially high by historical standards.

In Ackerman’s account, the inflation crisis is a fiction that the typical American will only encounter when “reading publications like Politico or the Washington Post as they report from the front lines of the inflation struggle (a shifting forward perimeter that forms a salient into the green rooms of the various Sunday morning talk shows).”

Finally, although the pandemic is far from over, case counts have been falling since mid-September, and voters have steadily downgraded the coronavirus as an issue priority. Since Biden’s approval has declined over that same period, COVID’s persistence isn’t a satisfying explanation for his plight.

In sum, Biden’s struggle to move his agenda through Congress is typical of modern presidents. The substance of that agenda is atypical in its popularity. And if we measure the economy’s performance by the abundance of jobs, the trend for real wage growth, the level of consumer spending, or strength of household balance sheets, the Biden economy is exceptionally strong. Factor in (historically modest) inflation, and it’s still hard to see why voters would consider the Biden economy anything worse than a mixed bag.

Or, rather, this is hard to see until one considers that America’s media landscape is structurally biased against the Democratic Party.

This bias has two dimensions. First, the American right has a much more potent propaganda apparatus than the Democrats do. In fact, conservative news outlets have become so dominant that the phrase “mainstream media” has become a misnomer. CNN is considered mainstream and Fox News right wing, but the latter is more prominent than the former: Throughout 2021, America’s most-watched cable-news channel has also been its most unabashedly anti-Biden.

Meanwhile, a majority of the top-ten news posts on Facebook on any given day tend to be from right-wing outlets.

One can argue that this reflects high consumer demand for conservative news rather than any conspiracy wrought by right-wing elites. Either way, though, the right’s dominance of the market for ideologically-oriented infotainment surely redounds to the Democrats’ disadvantage.

Of course, conservative media did not become a cultural force in just the past three months. So it can’t be uniquely responsible for the turn in public opinion against Biden.

What has (predictably) changed is the mainstream media’s posture toward the president. This was most overt in its coverage of the Afghanistan withdrawal, when the mainstream media subjected Biden to weeks of relentlessly (and, in my view, unjustifiably) negative coverage. But the media has also eroded Biden’s standing in a more insidious and less intentional way.

Back in March, the political scientist Matt Grossmann predicted that Biden would see his legislative agenda grow more unpopular in the coming months as the media lavished it with greater attention. Drawing on the research of fellow political scientist Mary Layton Atkinson, Grossmann noted that “major laws that pass by slim majorities get five times more media coverage than those that pass with large bipartisan majorities,” while “media coverage largely focuses on why the legislation was controversial or the legislative debate was acrimonious; only one-third of congressional coverage focuses on policy details.” As a result, “the public’s takeaway from a big piece of legislation is often that political interests dominate all else, which in turn can reduce support for legislation and raise public perceptions of partisanship and extremism.”

Grossmann suggests this dynamic may be a major cause of “thermostatic public opinion”: the electorate’s perennial tendency to shift right in its policy preferences when Democrats are in power and left when Republicans are in power.

The fact that media coverage tends to turn the public against major legislation regardless of its contents is not necessarily an indictment of the media. News outlets cover new developments. The substantive implications of policy proposals are relatively static. Machinations over which of those proposals will or will not be included in pending legislation, by contrast, can change on a daily basis.

Meanwhile, the audience for daily political news is not the median voter (who pays relatively little attention to politics) but rather high-volume news consumers. For the well informed, whether a perennially debated policy will or will not make it into law is more interesting than primers on what that policy would achieve. So the media isn’t doing anything nefarious when it privileges process over policy in its congressional coverage. But the effect of that prioritization has historically been to muddy the in-power party’s reputation with the general public.

Why it might still be “the economy, stupid.”

I think media dynamics have played a major role in Biden’s plight. But I’m not certain they’re the president’s primary problem.

First, I think there’s substantial evidence that disappointed Democrats are weighing heavily on Biden’s numbers. In Pew’s polling, between July and September, the president’s approval rating among Democratic voters fell by 13 points. Further, while Biden’s disapproval has soared since late summer, the Democratic Party’s advantage on the question “Which party do you want to control Congress?” has been comparatively stable, dropping from about 3.2 points in mid-August to 2.7 points today. That indicates there are a good number of loyal Democratic voters who have soured on the president but not on their party. Intuition would suggest that impatience with congressional negotiations over Biden’s agenda is fueling such discontent. And on Monday, a Washington Post report on the president’s declining standing among Virginia Democrats — in which several interviewees bemoaned Biden’s failure to whip “these two wild-card senators” into line — lent credence to that supposition.

Biden’s agenda might not be moving all that slowly relative to recent precedents. But that doesn’t mean voters aren’t responding directly to the objective fact of its long delay.

Coverage of contemporary economic conditions has been excessively negative, and the threat of sustained inflation strikes me as overblown. More fundamentally, I think the mainstream media routinely misleads the public about the causes of inflation and what a responsible policy solution to the problem would look like.

All that said, it seems clear that rising prices are a political problem for Biden and that this fact is not solely due to the media’s failings. Although public concern about inflation remains low by the standards of the 1970s, Ackerman is wrong to assert that “the public seems barely to notice the current inflation.” In a Fox News poll released late last month, 53 percent of voters said they were “extremely concerned” about inflation; no other issue attracted majoritarian concern. A CBS News–YouGov poll released around the same time found 60 percent of Americans saying that Biden isn’t focusing enough on inflation. In a contemporaneous CNBC survey, voters ranked inflation as “the most important issue facing the nation.”

It is true that price increases have been largely confined to a discrete set of goods. But those goods happen to be of extremely high salience for U.S. voters. According to AAA, America’s average gas price is 60 percent higher now than one year ago and 6.6 percent higher than one month ago. Historically, changes in presidential approval have often correlated with changes in gas prices. Food prices have also been increasing substantially. And again, for most workers, real wages have fallen over the course of this year. Meanwhile, America’s growth rate slowed in the third quarter as supply-chain disruptions dampened consumer spending.

Finally, while COVID is trending in the right direction, the Delta variant, combined with substantial resistance to vaccination, has prevented Biden from delivering the return to normalcy he had campaigned on.

All of which is to say: Media biases have been a real problem for Biden. But so have objective realities. And that’s good news for Democrats. It is within the party’s power to satisfy its disgruntled partisans by sending the Build Back Better agenda to Biden’s desk. And although the president’s capacity to bring down global commodity prices is limited, most analysts expect inflation to decline in the latter half of 2022.

Even if all goes well, the rightward tilt of America’s media landscape will remain a problem. And Democrats would be well advised to put more time and money into answering conservative media’s extraordinary success. But that’s a long-term project. The immediate challenge is to avoid a red-wave election in 2022. To do that, all Democrats must do is achieve near unanimity around a $1.75 trillion climate and social-welfare bill and then get lucky.