Teresa Helm was 22 years old when she was flown across the country for what she thought was an interview to be a private massage therapist for a wealthy Manhattan woman, Ghislaine Maxwell.

Arriving at Maxwell’s elegant Upper East Side townhouse, where she says she was greeted by a butler wearing coattails and carrying a silver tray, Helm thought she had happened upon “the chance of a lifetime” that day in 2002. Maxwell was exceedingly polite and inquisitive of Helm, asking of her upbringing in Ohio and remarking on the fact that their birthdays are one day apart. When Helm went to the bathroom, she noticed a framed photo of Maxwell and Bill Clinton on the wall.

After Helm gave Maxwell a massage, Maxwell said Helm should go to “her friend Jeffrey’s” for the second part of the interview. “If you love my place, just wait until you see Jeffrey’s,” Maxwell told her. “It’s the largest townhome in Manhattan.”

“And she looked at me and said directly, ‘Make sure you give Jeffrey what he wants. Jeffrey always gets what he wants.’ I tried to normalize what she said, and I thought, Okay, this man probably gets a lot of massages, and she’s saying he knows what he wants.”

“At the time, I trusted this woman,” Helm says. “And I didn’t have any reason to believe she was getting ready to send me off to a predator.”

Later that day, Helm went to Jeffrey Epstein’s mansion a few blocks north, where, after she watched him finish his dinner in the kitchen, she says he sexually assaulted her in an upstairs hallway. “It destroyed a part of me,” Helm says of her encounters with Maxwell and Epstein. “This woman, she’s a master manipulator of human emotion.”

Nearly two decades after Helm’s fleeting but indelible experiences with Maxwell and Epstein, no one has been punished for the alleged sex-trafficking ring the two operated for years. Epstein finally faced the prospect of federal prosecution in 2019, when the Manhattan U.S. Attorney’s office nabbed him on a return trip from Paris and charged him with the sex trafficking of minors and conspiracy. But that August, just one month after he was arrested, he committed suicide in his jail cell while awaiting trial.

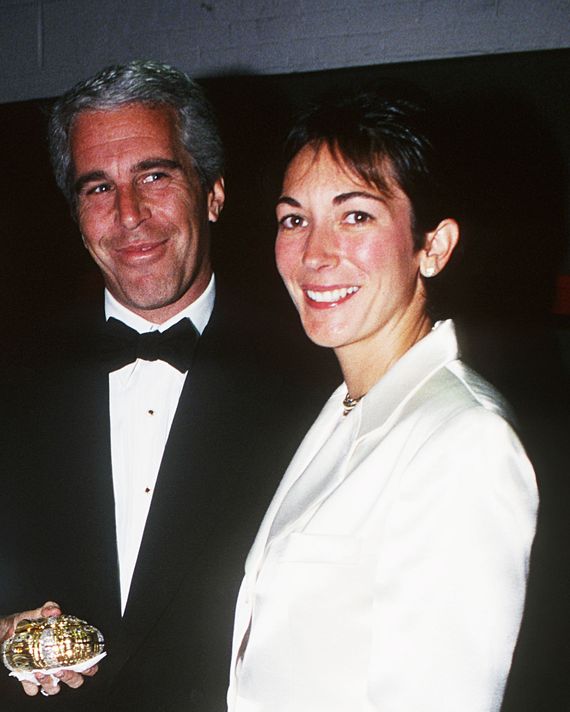

Now, in his absence, Maxwell may finally pay a price for allegedly helping to victimize so many girls and young women. Epstein’s onetime girlfriend, longtime companion, and his alleged accomplice in abuse, Maxwell, 59, will stand trial in Manhattan federal court starting on November 29 for the sex trafficking of a 14-year-old girl and for recruiting, grooming, or sexually abusing three other girls alongside Epstein.

Helm plans to travel from her home in Naples, Florida, to watch Maxwell in court along with a group of other victims. For some, including some of the victims cited in the charges against Maxwell, which stretch back to conduct that allegedly occurred in 1994, this trial is perhaps their last chance to get justice. “I do anticipate looking directly at her, and I don’t know what I’ll feel,” Helm says. “I don’t believe that she should ever be free because there are many of us on the outside — we are not sitting in jail cells, and we are still not free from what she has done and what she has caused.”

A British heiress and socialite once defined by her chic pixie haircut and posh accent, these days Maxwell is practically unrecognizable as the woman for years pictured on Epstein’s arm at Mar-a-Lago and Cipriani. Arriving at a hearing earlier this month, she shuffled into the courtroom flanked by U.S. Marshals, her wrists and ankles shackled with heavy chains that clanked when she walked. Her dark hair is frizzy and shoulder length, and she wore a baggy, jail-issued outfit: navy shirt, pants, and canvas shoes. The only echo of her former self came when she spoke, telling the judge in her clipped pronunciation, “I have not committed any crimes,” and when, during a break in the proceedings, she turned to blow a series of kisses to a woman in a red beret who appeared to be her sister.

But her former self — the alleged, secret side of it — will be on display later this month in evidence presented by prosecutors when they try to convince a jury that Maxwell “assisted, facilitated and contributed to Jeffrey Epstein’s abuse of minor girls,” as they wrote in their indictment.

According to prosecutors, Maxwell used her appearance as a sophisticated, glamorous woman to pull girls as young as 14 into Epstein’s orbit. She attempted to befriend them, prosecutors wrote, taking them on shopping trips or sending them lingerie; bringing them to the movies; inquiring about their families, school, and friends. Then, according to court papers, she would try to engage in grooming behavior by undressing in front of them or discussing sexual topics. And once she had convinced a girl to give Epstein a massage, often a sexualized massage in which the girl was partially or fully nude, Maxwell would remain in the room while a sex act occurred between Epstein and the girl, a step that prosecutors said in court papers “helped put the victims at ease because an adult woman was present.” In addition, prosecutors allege, in some instances, Maxwell herself “participated in the sexual abuse of minor victims.”

Maxwell denies all of this, and in court filings, her lawyers have accused the government of having conducted a “hasty and sloppy” investigation in the wake of Epstein’s suicide as it scrambled to file a case against someone else in his absence, alleging the “government substituted Ms. Maxwell for Jeffrey Epstein after his death.”

Maxwell faces up to 80 years in prison if convicted of all charges (she will face a second trial for perjury charges for allegedly lying under oath in a 2016 deposition about whether she was aware of Epstein’s scheme to recruit underage girls for sexual massages).

The six-week trial promises to deliver some hurdles for both the prosecution and the defense. For one thing, the charges concern alleged conduct that is relatively dated, beginning in 1994 and ending in 2004. The case is expected to rely heavily on witness testimony — in particular from the four women cited in the indictment, who will be asked to recall traumatic events that occurred when they were minors — and those years may take a toll on both their memories and the existence of documentary evidence that might either support or undermine their stories.

“The prosecution faces some real challenges with corroboration due to the passage of time, and the defense needs to avoid falling into the trap of relying too much on holes in memory,” said Martin Bell, a former federal prosecutor in the Manhattan U.S. Attorney’s office. “Pointing at little gaps here and there and going ‘Aha!’ is a less effective strategy than one might think.”

Another former federal prosecutor in that office, Jessica Roth, noted that prosecutors wrote the charges without tying specific acts to specific dates, a choice that will allow prosecutors to avoid having to prove those details from decades ago and could make it harder for Maxwell’s lawyers to dispute certain events.

With hard dates, “one could try to raise doubt about whether the victim’s memory was perhaps a little off to suggest Maxwell wasn’t present on that date,” Roth said. “But the lack of precision about a particular date makes that harder to do. I think the indictment was drawn purposely to avoid having to prove with precision what occurred on a particular date.”

Earlier this month, the judge presiding over the case imposed what may be another hurdle for the defense: She ruled that certain witnesses will be allowed to testify under a pseudonym or using only their first name. Though that is a rarity, two recent federal cases in New York have featured anonymous witnesses: the trials of R. Kelly and Keith Raniere, leader of the sex cult NXIVM (both men were convicted).

Maxwell’s lawyers fought this outcome hard, arguing that allowing witnesses to remain anonymous would prejudice the jury against their client.

When it comes to those witnesses, all of them will be women, as will three of the four prosecutors on the case as well as several of Maxwell’s defense attorneys, including the lawyer who has been taking the lead in pretrial proceedings, Bobbi Sternheim. To experienced trial lawyers, that is no coincidence.

“When you’re talking about sex, a woman questioning a woman can allow you to dig deeper on some of those issues without looking offensive or aggressive,” said Moira Penza, the lead prosecutor on the NXIVM case. “I do think it is a good, strategic choice.”

One defense tactic Maxwell may employ is to allege that she too was a victim of Epstein’s. Several other women who have been accused of recruiting girls for Epstein have since claimed they were subject to abuse. “I think that there will probably be aspects of her presenting herself as a victim,” Penza said, but she added that Maxwell’s age — she was only nine years younger than Epstein — and the power that she wielded with him would likely undercut that argument.

For many observers of the trial, the biggest question will be whether Maxwell will take the stand in her own defense. Though it is often unwise for a defendant to do so because of the danger of being confronted during cross-examination, the calculus may be a bit different for Maxwell, according to criminal-defense attorneys.

There is likely less documentary evidence to contend with because the case is so old, said Duncan Levin, a criminal-defense attorney whose clients have included the Seagram’s heiress and former NXIVM leader Clare Bronfman. And, Levin said, like Elizabeth Holmes, another female defendant currently on trial, Maxwell is known for her power of persuasion.

“These are people who are extremely convincing,” Levin said, “and all they have to do at this point is convince 12 more people.”

As for Helm, who has followed Maxwell’s repeated (and failed) attempts to be released on bail, including her initial proposal that she be allowed to live in a luxury hotel pending trial, she said if Maxwell does testify, it will be because she thinks she can continue to bend people — in this case, jurors — to her will. Said Helm, “She believes that she still controls her reality.”

Related

- How Leslie Wexner Helped Create Jeffrey Epstein

- Ghislaine Maxwell Gets 20 Years

- There Goes the Last Chance to Learn Jeffrey Epstein’s Secrets