Ever since Russia invaded Ukraine on February 24, the aggressive sanctions response by the U.S. has been undermined by the fact that, for decades, Russian oligarchs have laundered their ill-gotten gains through the American financial system. It’s been an open secret that some of Russian president Vladimir Putin’s closest allies own luxury apartments in New York, though it’s unclear exactly how much U.S. real estate is secretly financed by the oligarchs. There are other problems as well. For example, even if U.S. authorities believe a property was purchased using stolen or laundered money, they have to prove it in court — which can be difficult, expensive, and time-consuming if the owners fight the allegations. To facilitate the process, the federal government recently formed Task Force KleptoCapture; the joint operation among several agencies aims to get to the root of how sanctioned oligarchs are hiding their money. There are also groups of vigilantes trying to find oligarchs’ apartments themselves.

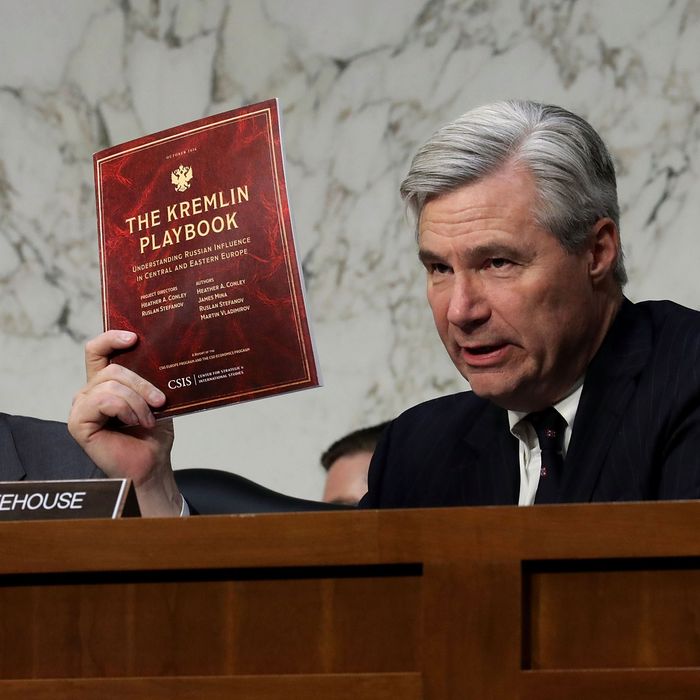

Last week, a bipartisan group of senators introduced the Asset Seizure for Ukraine Reconstruction Act, which would allow the federal government to more easily seize and liquidate the holdings of Russian oligarchs and use that money to fund the Ukrainian resistance. The bill is sponsored by Sheldon Whitehouse and has backing from his fellow Democratic senator Richard Blumenthal as well as Republican senators Lindsey Graham and Roger Wicker. If passed, it would give the president wartimelike powers to target Russian businesspeople and more easily sell off whatever assets they have — plus give people a bounty for dropping a dime on the Russians. I talked with Senator Whitehouse about how the bill came to be, what the senators hope to accomplish, and what this would mean for people’s fundamental rights in the U.S.

How did this bill come into existence?

The bipartisan agreement around measures like this was forged at February’s Munich Security Conference among the American delegation. We worked with Senator Graham, in particular, to write it up correctly in a way that he and Senators Wicker and Blumenthal would all be aligned with. Our sense was that a critical way to put pressure on Putin was to squeeze his corrupt oligarchs — much in the way that the Ukrainian oligarchs turned on former Ukrainian president Viktor Yanukovych, causing him to flee to Russia when his position became untenable and started to affect their interests.

The Munich conference took place a few days prior to the Russian invasion of Ukraine. So this was what? A deterrent? A potential option if Putin did decide to pull the trigger and invade?

We were getting pretty solid briefings and warnings that the decision to invade had already been made, and that it was only a matter of time until the actual commencement of hostilities. So we were trying to address how we could improve on the general sanctions regime by allowing more aggressive deployment against oligarchs’ assets. What we’ve tried to do in this bill is to couch the president’s power to seize foreign oligarchs’ assets in the executive national security powers. If you’re trying to seize an American’s assets, there’s an enormous amount of procedure and due process required. That’s one extreme. The other extreme is when you’re actually at war, everything is up for grabs and considered spoils of war; there’s no procedure whatsoever. We’re trying to forge a middle path in which assets can be rapidly seized, then we sort out who has what rights but from a position of having custody of the asset.

The Treasury Department has offered bounties, as it were, for whistleblowers.

Yes. We’re happy about all of that.

Right now, Treasury is in the process of rewriting the rules around transparency for real-estate ownership.

Two things are going on. The rules regarding the Corporate Transparency Act, the “beneficial ownership of shell corporations” measure, are in their final phases over at Treasury, and we’re satisfied with all the initial signals. And then, I think, separately, they’re expanding what they called the Geographic Targeting Orders, which focus on real estate and have proved to be quite effective at dealing with some of the high-impact areas like Miami and New York.

So you’re happy with what you’re hearing about the expansion of the rules around beneficial ownership of shell corporations. Can you say more about that?

Well, we were turning into a great big Cayman Islands. And that’s a very bad thing for the U.S. for a number of reasons, not the least of which is that “land of the free and home of the brave” is a much better brand than “land where the crooked hide their money.” It took a lot of resistance to pass that bill. And when you get a bill passed, you’re always worried about how energetic the regulatory implementation will be. I’ve been satisfied with how energetic Treasury has been in drafting the regulations and in its outreach to DOJ and others to make sure that they do this right. So I put that in the win column.

Do you have a sense that there is opposition from real-estate lobbies to increasing transparency at this moment?

I’m confident there will be.

Is most of the money that oligarchs stash in the U.S. funneled through real estate?

We’ll learn a lot more as the shell corporations have to be opened up to FinCEN, the Treasury’s Financial Crimes Enforcement Network, but I strongly suspect that the bulk of it is real estate. Although, the extent to which hedge funds and stock accounts can compete is unknown. It would be logical to think that real estate is No. 1.

Do you have any concerns that there could be repercussions down the line to people’s rights?

No, not really. First of all, we’re dealing with a foreign population of enemy collaborators. We’re not dealing with American citizens, who have a different set of rights.

But Russia, right now, is not considered an enemy, is it? We’re not at war.

We are not at war, but we are trying to couch this as much as possible in the national security powers of the president so that these tools can be brought to bear without being tangled up in unnecessary procedure that a foreign oligarch is not entitled to, since he’s not an American citizen and not even in the United States.

A little bit of a sidebar, if you don’t mind: I used to harangue the Department of Justice about shutting down botnets. After Microsoft had a successful case, it began shutting down botnets. What they would do is go into court and say, “Anybody who claims this botnet, please show yourself and we’ll hear you out. You get all the due process you want. If you don’t show up, we’re going to take down the botnet.” And, of course, nobody ever showed up. Who wants to step into court and say, “Yes, that’s my botnet”? In a similar vein, if you grab a ginormous megayacht that is sheltered through five, six, or seven corporate shells, Cypriot bank accounts, and Cayman Islands screens, then what happens next? Does the oligarch show up to say, “That’s not actually my boat”? What’s he doing in the courtroom? And if somebody else shows up to say, “That’s actually my boat,” you’ve got some procedure to test that proposition, in the way it should be tested, under oath with discovery.

What we’re trying to do here is allow the government to act based on information that clearly places assets in the hands of oligarchs, whether that’s insider information from the captain of the vessel or information that our national intelligence service has gathered, so that we know whose property this is. Then you don’t have to jump through all the hoops of breaking through all the multiple shells. You just seize it based on good and solid evidence, and let them come and try to disprove it. I think a lot of times, they just won’t, because they can’t do it.

Your bill would expire after two years. Why?

This was cast as a temporary measure to see how it works and try to eliminate concerns. Any hesitation about this power is relieved a bit by there being a sunset.

What about billionaires from other countries that have human-rights problems — Chinese billionaires who profit from encampments of the Uighur population, people like that?

My personal goal in all of this — not just in this bill but in the entire effort across the board: the funding efforts, the empowerment and better cooperation among the different federal agencies, the other legislation and oversights we are working on in this area — is making sure that we have the capability to go after this international dark economy more or less wherever it rears its ugly head. Hiding behind anonymity in rule of law jurisdictions is essential life support for kleptocracy, corruption, and criminality, which imperils Americans everywhere. We’ve been slow to see this as a national security problem, and I think we have not resourced going after that dark economy adequately yet. So I’ll take whatever small measures I can get.

I don’t want to speak to particular examples, but in general I think that there is a dark economy out there that supports a lot of evil in the world, and we’ve been negligent about directing spotlights onto it to put a stop to that evil.

This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

More on Ukraine

- House Passes Ukraine, Israel Aid: How It Happened

- Trump’s Plan for Every Foreign-Policy Problem Is Himself

- Putin Is Winning — and He’s Flaunting It