This article was featured in One Great Story, New York’s reading recommendation newsletter. Sign up here to get it nightly.

Steve Barnes was furious. Over the past 25 years, he had helped turn a small-time Buffalo personal-injury law firm into a New York institution, one with eye-popping profits and an empire of advertisements so widespread you wondered if everyone who got into an accident in the state would end up as its client. But now everything he’d built was at risk of falling apart. How could anyone, especially his own partner, Ross Cellino, want to turn off the rivers of green that flowed into their coffers? It was April 2017, and Barnes’s emails boiled with frustration, each one a verbal roundhouse to the partner yoked to him by an ampersand and thousands of TV, radio, and billboard spots.

“We have made 10+ each for the last few years, with nothing but blue sky in the future. What part of THAT are you unhappy with?” Barnes wrote his partner. (That “10+”: That’s millions of dollars, each.) “You know any other lawyers who are making 10 a year? I don’t.”

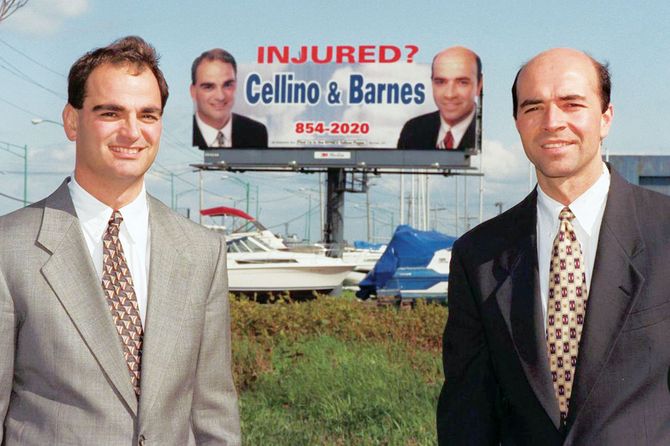

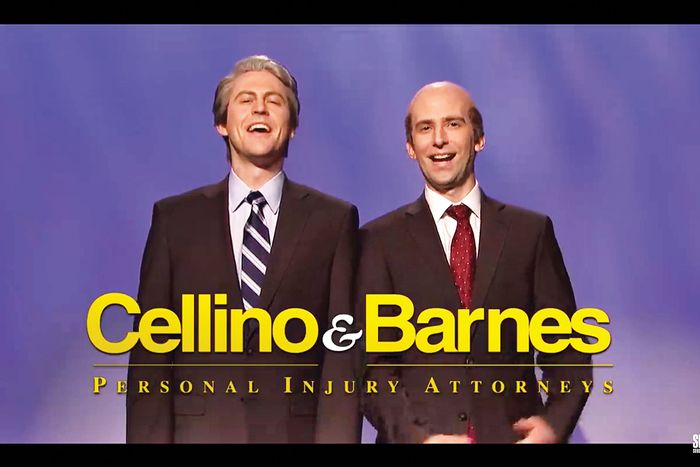

Not likely. Not in Buffalo, for sure. And almost nowhere else in the vast legal netherworld of personal-injury firms, where decorum gives way to inescapable billboards, catchy jingles, and blunt commercials that trumpet a better-than-any-rival’s ability to get you money. That’s where Cellino & Barnes presided: Barnes, the former Marine with the gravelly voice and startling intensity, and Cellino, the cuddly-looking Everyman with nerdy glasses. TV. Radio. Bus stops. Subway entrances. Everyone knew Cellino & Barnes — most people even knew that Barnes was the bald one with the strained smile, staring at the camera for just a bit too long, and that Cellino was, well, not the bald one.

And the jingle. Good God, the jingle. Even if you would never dream of trusting your legal representation to a commercial, it set up camp in your brain and never left. Eight hundred, eight, eight, eight, eight, eight, eight, eight. In New York City, Cellino & Barnes was as familiar as yellow cabs, halal carts, or a subway “Showtime!”

Yet largely out of sight of their legions of potential clients, the two men had been sparring for years about the need for autonomy and decision-making power, about family, about the quest to expand, and about respect. When their feud was made public later that spring, after Cellino filed a petition to dissolve the firm, it exposed Cellino & Barnes’s tightly controlled innards and drew countless rubberneckers. There would be lawsuits, appeals, affidavits — so many affidavits — and, of course, billboards (and a lawsuit involving billboards). There were stories in the tabloids about how Cellino accused Barnes of being “dictatorial,” about how Cellino said the staff should follow him, the first name in the duo, because “no one ever calls their motorcycle a Davidson.” Colleagues would testify. So would life partners, assistants, and accountants.

The fight revealed more than just financial dirty laundry and wounded feelings. It captured the birth and boom of what has become one of the most caricatured areas of the law — a pop-culture staple that often earns its reputation as ambulance chasing but also delivers on its promise as one of the most direct ways to bring justice, and fair compensation, to the least powerful members of society. It is a world that isn’t going away anytime soon, even if the men who elevated the New York car-crash lawsuit to a kind of high art have themselves joined the ranks of the injured.

The two men came together by chance. Cellino’s father, Ross Sr., had hung out a shingle back in the more staid legal world of 1950s Buffalo. He was the son of a poor farmer and desperate to climb to stability. When he died last year, his memorial Mass program included a bullet-point list of jobs he’d held as he scrapped: box-factory laborer, bowling-alley pin sticker, waiter, income-tax preparer, and worker “at Bethlehem Steel on the big cold saw, this caused his partial hearing loss from the high pitch noise.”

The steel job was at night to help finance law school during the day. The firm he launched with a local lawyer took anything that came in the door: real estate, criminal cases, trusts, some personal injury. Whatever paid the bills for Cellino Sr.’s growing brood of nine children.

When Cellino Jr. (brawnier than you might expect, ruddy, an eventual father of six) graduated from law school, Buffalo wasn’t exactly a golden land of opportunity. As he told me over his dining-room table before the pandemic, he worked DWI and real-estate cases on his own his first year out in the early ’80s — 80 hours a week for $9,000 a year. He became intrigued by the ads some attorneys were placing in the local Yellow Pages. Full-page displays, the back cover for about $100,000. He took a few of the lawyers behind the ads out to lunch, but when he started asking questions, they tried to steer their young competitor away, downplaying the approach. No, they told him, it’s not really worth it. Don’t bother.

The brush-off only encouraged him. Cellino bought a business-card-size ad. Then a half-page and more. Nothing too snazzy. If the ads brought in just one $300,000 case, he reasoned, that’s $100,000 in attorney’s fees. “It encouraged me to become more aggressive,” he told me. His competitors, he said, had lied. Ads worked.

Eventually, Cellino started working with his father. When it came time for his father to retire in the early ’90s, Cellino and his father’s partners were eager to find some young blood. A local lawyer named Richard Barnes reached out with a suggestion: How about his younger brother, Steve?

Steve Barnes was the kind of guy who finished law school then signed up for the Marines. He served as a military lawyer and briefly saw action during the Gulf War in a tank battalion in Kuwait. Barnes says his decision to enlist was a primal compulsion. “Almost analogous to a woman’s desire to give birth,” he says. “Maybe that’s one of the reasons that man has been involved in so many wars over so many millennia, because of this innate desire on the part of men to fight each other and kind of have that experience in their lives.” Rich Barnes once told the Buffalo News that his brother can be a driven guy: “He trains to make himself physically fit to the extreme. He will hike 50 miles from Buffalo to Ellicottville with a 60-pound weight strapped to his back. He’s done it many times.”

Steve was working at a large corporate-defense office when the Cellino firm approached him about joining forces. It was a tiny operation, but it wasn’t just a job, it was a shot at a share of the pot: a chance for something big. Cellino remembers Barnes called asking if the firm had made a decision the day after their initial conversation. Cellino loved the raw aggression. “This has got to be the right guy,” Cellino says he thought. “I was like that too. I wanted to grow.”

Though Cellino would later cultivate an image as a family man, his early hunger was palpable. Michael Beebe, a former Buffalo News reporter, remembers meeting Cellino right when he was taking over from his father. “He got a list of all the people that owed his father and his father’s firm money and went after them,” Beebe says. “I had a case involving a poor guy over on the East Side of Buffalo that claimed this lawyer was after him to pay his past rent and past water bills and things like that. So I met with Ross very briefly, and he says, ‘Look, they owe my father money. I’m here, and I’m going to get the money back.’ He was just matter-of-fact. It didn’t matter how poor this guy was.”

Barnes signed on. Eventually, the Old Guard left. As Cellino & Barnes, the pair made a critical decision: From then on, it would be all injury law, all the time. That meant taking cases on contingency — the client paid no money up front, and the attorneys kept one-third of whatever was won, minus costs. But injury clients aren’t usually repeat customers (unless they’re really unlucky or terrible drivers). So to grow, the firm needed a lot of cases.

Early on, Cellino and Barnes heard about a lawyer in New Orleans, Morris Bart, who was beginning to dominate the local airwaves. They flew down to see him. His advice was simple and profound: If you want to succeed, find out how much your biggest competitor is spending on ads and double it.

Bart, whose practice now spends upwards of $25 million a year on advertising, stands by that wisdom. “It was pretty easy in hindsight,” he says. “You cobble together money, make the ads, and the phone rings.” But when Bart started, it was revolutionary. Traditionally, the practice of law had had an aura of public service; that lawyers didn’t advertise was an ethical cornerstone of the profession. Then, in the ’60s and ’70s, a series of changes meant to give more people access to the legal process — the right to counsel for poor defendants, expanding use of powerful “class actions” to bring big lawsuits, and a rising consumer-focused mindset in government — created an environment that opened the door to legal advertising. In 1977, the Supreme Court heard the case of a “legal clinic,” a law practice that specializes in low-cost, routine legal help. The clinic’s lawyers wanted to advertise their rates so the average Joe could make a wise decision. The court agreed, on First Amendment grounds, and the advertising restrictions on lawyers came crashing down. “No one thought attorney advertising would be used by personal-injury lawyers,” says Stanford Law School professor Nora Engstrom, “including the Supreme Court.”

But by the ’90s, thanks to pioneers like Bart, legal advertising had become an obvious path for hustling lawyers, and Cellino and Barnes were all in. Following Bart’s advice, they plowed much of their profits from big settlements back into advertising.

In 1997, five years after Barnes was hired, their practice had just three lawyers. Then they decided to bring on a nonlawyer with an M.B.A., Daryl Ciambella, who was charged with writing a business plan and developing some television commercials.

“That showed the balls they had,” says Mark Cantor, a local attorney who worked with Rich Barnes. He recalls hearing that the firm had taken the entirety of its fee for a $3 million settlement and used it to make ads. “At that time, when lawyers settled cases for lots of money, you take the money. They didn’t take one penny of it. That was incredible to have that much faith in advertising.”

Cantor wasn’t the only Buffalo lawyer to take notice. Other local attorneys griped that their clients were being lured away by Cellino & Barnes’s aggressive advertising. “That’s what sticks in the craw of most lawyers in western New York,” griped one personal-injury attorney. “They are financially successful not because of the good job done on previous cases but because of advertising on cases.”

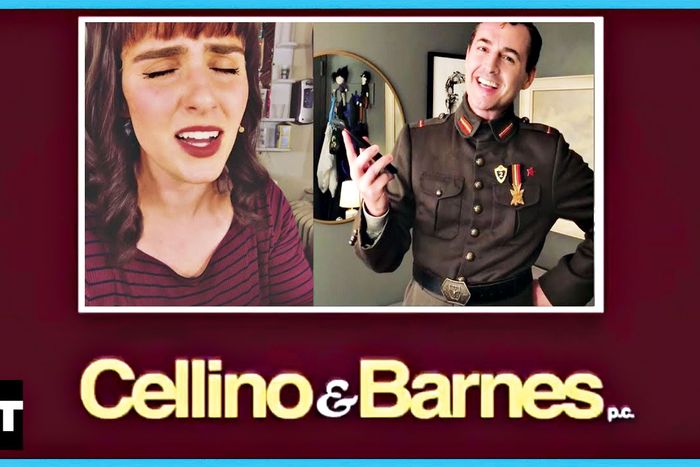

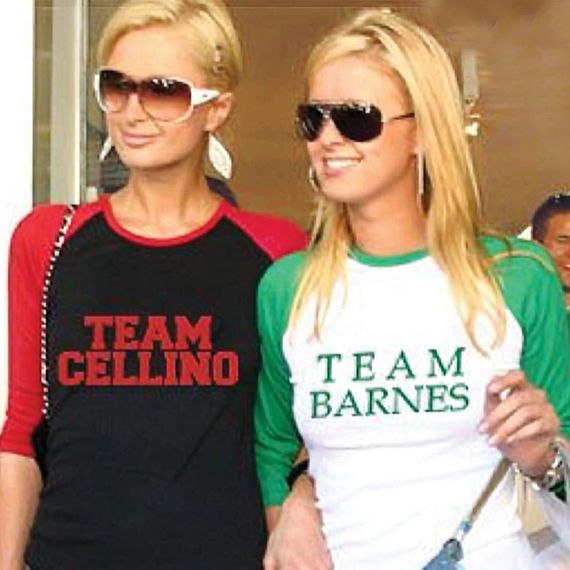

The firm’s draw only expanded after the partners commissioned their jingle: grand but gentle, enthusiastic but sweet. Undeniably catchy, despite having no rhymes and nothing all that distinctive about it, aside from how relentlessly it has appeared on television and radio. “Cellino & Barnes. The Injury Attorneys,” and then the phone number. (In later renditions, they dropped the “the.”) The jingle has sparked a singing challenge among Broadway casts and a spoof on Saturday Night Live. When the spread of COVID-19 led to public-health warnings to wash your hands for the length of time it takes to sing “Happy Birthday” twice, the Cellino & Barnes Twitter account suggested a much more enjoyable tune. When Chrissy Teigen tweeted her devastation at the news of Cellino & Barnes’s breakup, the reason was clear: “The song sucks now. We must reunite them.”

Barnes is a bit less romantic about it. “Jingles work,” he says. “Is there a great magic to it? I don’t know. I think there’s been more said about our jingle because lawyers weren’t doing jingles and now lawyers do jingles.”

Even with the ads, the firm probably never would have reached the heights it did without one person: a tool-and-die-maker named Mark Rappold.

Rappold doesn’t trust easily. He had seen some of the firm’s commercials on TV. He’d seen the billboards, too. But he wasn’t thinking about any of that when, in 1998, he and his wife heard their son David had been horribly injured in a high-speed car crash. David had just finished his first year of law school. His friend was driving, hustling up the New York State Thruway, with David in the passenger seat; the friend switched lanes, cutting off the car behind him. Incensed, the guy in the other car flashed his lights and tailed closely. The trailing car then raced ahead in the other lane, and the friend sped up, keeping pace behind. The police would call it “road tag.” At 85 miles an hour, the other car sliced back in front, then hit the brakes. The friend swerved, lost control, and spun into the median. The car slammed into a tree.

David had a massive brain injury. “He is for the most part paralyzed on the left side of his body,” an appeals court wrote in 2001. “He cannot feed or groom himself, walk, or use a motorized wheelchair because of his cognitive and/or physical limitations. He can speak only a few words, and he communicates by blinking his eyes, making hand gestures, and shaking his head.”

Rappold didn’t know what was in store for David or the rest of his family. But he knew he needed a lawyer immediately. Without justice for his son, there would be nothing to pay for the towering medical and rehabilitation bills that awaited him. Rappold was unimpressed with the first lawyer he met with, but a neighbor mentioned the guy from the ads, a nice guy he had gone to school with: Ross Cellino.

Rappold drove to see Cellino, unannounced, on a Sunday afternoon. Cellino was painting his house. His wife was gardening. “He says, ‘Can I help you?’ ” recalls Rappold. “I go, ‘Yes, I’m looking for a lawyer because my son was in a tragic car accident.’ Well, he dropped everything he was doing to talk to me. I mean, he didn’t even think twice.”

The rapport was instant. “You don’t even know he’s a lawyer,” says Rappold. “You don’t even know it. He talks like just — a person.”

When Rappold met Steve Barnes a few days later, he seemed like Cellino’s perfect foil. “He was the opposite of Ross. I could tell he was power driven,” Rappold says. But it worked. “They complemented each other pretty good, I’ll tell you that right now. Steve, boy … he could really tear somebody apart on the witness stand.” And Cellino delivered the kind of closing statement that made the jury melt. “Nobody could talk to the jurors like Ross Cellino,” Rappold remembers. “The way he talked to them, the way he looked at them, the way he appealed to them. ‘Don’t Mr. and Mrs. Rappold deserve a chance to have a life of their own? But they can’t have a life of their own without the resources to help them.’ ”

Cellino and Barnes didn’t tell Rappold they were planning to ask for $55 million, not until just before it was time. Rappold thought that much money was ludicrous, greedy even. The trial would yield one of the largest personal-injury verdicts New York had ever seen: $47 million. As the Buffalo personal-injury lawyer — no fan of the firm, which he says “really destroyed what was a close-knit community here among plaintiffs’ lawyers” — put it, “That [verdict] was the bellwether. After that, it was no holds barred.”

In the hallway after the verdict, Cellino and Barnes celebrated with the firm’s lawyers and paralegals. Rappold had no part of it. “I would give every penny of that judgment back to have my son back,” he says. Cellino eventually noticed Rappold’s pain, Rappold says. “I know this is a hollow victory for you,” he said. Steve partied on.

An appeals court would knock the judgment down to $16 million. The money still provides for David Rappold’s care, but it didn’t make them rich. The firm ended up with $5.5 million — and valuable publicity.

After the judgment, the firm grew quickly. In 2002, it opened a satellite office in Buffalo — across the street from the area’s largest trauma hospital. The branch has two huge red signs that light up at night. By 2005, it had 40 lawyers. “It was like a hospital waiting room in there,” says Beebe, the former Buffalo News reporter, of the main office in Buffalo. “People would come in on crutches and wheelchairs, and everybody is going to get their piece of money.” The firm had expanded into mass torts, signing up large numbers of people who had suffered heart attacks and strokes after taking the prescription drug Vioxx.

Business was good, and not just for the names on the door. In 2004, a top earner at the firm, Joseph Dietrich III, made nearly a million dollars — a figure we know because when Dietrich left the firm the following year, and took his clients with him, the firm sued, saying all those accident victims had become clients because of its advertising campaign. That lawsuit also highlighted the sometimes aggressive tactics the firm would employ to maximize revenues. When clients left to seek other representation, Cellino & Barnes would often sue, demanding a cut of the settlement — even though the firm itself had developed what a judge in one lawsuit called “a reputation for stealing clients.”

But it was the firm’s efforts to maximize paydays for its clients that would get it into more serious trouble. After the Rappold judgment, Cellino & Barnes hired outside lawyers to help keep the verdict amount from getting reduced — and billed the Rappolds $300,000 for their services. The Rappolds, who just wanted to settle and move on, were pissed off when they found out their lawyers were billing them to extend the fight. Rappold filed a complaint with the state’s Attorney Grievance Committee.

Vincent Scarsella headed the investigation for the committee. When he first looked into the case, he did not see much wrong with the billing. But as investigators rummaged through files, they found something else: The firm had been lending money to clients at interest rates of 19 to 24 percent, first through a mortgage company it bought in 1994 and later through an arrangement with a company owned by Cellino’s cousin.

Lawyers regularly advance clients the costs of litigation, such as filing fees and paying for experts, in the expectation that they will be paid back if the suit is successful. But they aren’t supposed to lend clients money against the potential settlement, an arrangement that might end up indebting them to the very lawyers who are supposed to be working on their behalf. There is actually an entire industry of other companies that lend money to plaintiffs in exchange for a piece of an eventual settlement, often at interest rates of as high as 50 percent. Those loans are legal because they are “nonrecourse,” meaning that if the lawsuit fails, the plaintiff doesn’t have to repay them.

Scarsella says Cellino and Barnes tried to paint their actions as “altruistic” because they were offering lower interest rates on their loans than those other companies were. But he thought such arrangements represented a clear conflict of interest — especially when he learned that the Rappolds had received assistance from Cellino & Barnes to pay not only for David’s nursing care but also to build a cabin. The appellate justices who evaluated the case agreed: They found against both Cellino and Barnes for making loans to clients with interest, which both lawyers had participated in. (Cellino and Barnes said they were following legal advice, no clients had been harmed, and they stopped as soon as they found out the practice wasn’t permissible.)

The justices also found a second infraction: A retainer agreement Cellino had filed with a new client did not match the arrangement the firm had actually agreed to with the client. Cellino tried to explain it away as an honest mistake, saying he had inadvertently signed a preprinted retainer agreement, but the justices concluded he had filed a false document — a much more serious issue. Barnes ended up with a censure. Cellino was suspended for six months.

Cellino has adamantly maintained that he did nothing dishonest. Even Scarsella, who agrees with the court’s opinion, thinks it’s unfair if the public sees Cellino in a worse light. “I think they were both in it,” he said. “I don’t agree with that at all, that one of them was the mastermind or something. That’s not what the facts showed, and that’s not what the court found.”

Cellino’s suspension rocked the firm. “It was almost like a death,” one former employee says. “Everyone felt bad that it was him that got the blame for it all. He kinda was the scapegoat on that one.” Before they knew what the final ruling would be, Cellino and Barnes had taken steps to ensure that their practice would survive even if they were both suspended. To keep a recognizable name on the door, they had turned to Barnes’s brother, Rich, enticing him with a big salary — $350,000 and a 10 percent cut of the fees in his cases — and made new ads in preparation for a future as the Barnes Firm.

In the end, it took 19 months for Cellino to be readmitted to the practice of law, while other issues, never publicly disclosed, were resolved. According to his father, he spent much of his time in the professional wilderness doing manual labor: building fences, planting trees, and helping out at Habitat for Humanity. When Cellino returned to the firm, both he and Barnes agreed that his suspension had shifted things. They just didn’t agree on how. “I did not foresee the drastic effect the suspension would have on Ross, and when he was finally reinstated from his suspension, he was a changed man,” Barnes later said in an affidavit. “The friend and co-owner that I knew did not return from the suspension. Rather, a drastically altered and affected Ross returned and withdrew from his prior roles and duties with C&B.”

In an email sent after their relationship had deteriorated, Barnes went further: “It is ironic in the extreme that you have become so bitter toward me — the one person in your life who made sure that you were welcomed back to share in the bounty of this incredibly successful firm, the management of which you abdicated years ago.”

Cellino argued that he had a right to return but that Barnes had been less than welcoming. In a 2018 deposition, he said it took months to get Barnes to change the firm’s name back. After his return, Cellino continued to be involved in many aspects of the firm’s management: pursuing lines of credit from the bank, approving and cutting ads, strategizing about expansion. But he was rarely settling his own cases or driving the firm’s decisions. “I felt guilty making $8 million a year,” he recalls telling Barnes at a meeting, “when I’m not producing revenue for the firm by resolving cases like I used to.” But he denies that he ever “abdicated” anything.

Part of the problem was Daryl Ciambella, the M.B.A. the partners had hired to help build the business. Ciambella was now a leading force in the firm, and Cellino felt that Barnes tended to side with him. “I was basically pushed to the side and not allowed to voice my opinion,” he said in the deposition. It was Barnes who had changed, Cellino argued, refusing to share control and rejecting his input. The idea that he wasn’t participating irked him. “I enjoy coming to the office and interacting with the staff and attorneys,” Cellino vented at Barnes in an email. “When you come into the office, you appear to remain in your office and rarely come out to talk to anyone.”

Barnes acknowledges that Ciambella’s ascendancy was a source of tension with his partner. “Daryl in many ways was the brains behind” much of the firm’s success, he says. “I don’t know if Ross doesn’t want to admit that. I think he knows it in his heart.” He does concede that Ciambella “rubs [some people] the wrong way.”

Adding to the tension was Ellen Sturm, Barnes’s girlfriend, whom he brought into the firm in 2009. Both Cellino and Barnes agree that Sturm’s credentials are impressive, especially for a personal-injury lawyer: a summa cum laude graduate of the University at Buffalo School of Law, she worked as a confidential law clerk to a state appellate judge and then at the white-shoe firm Skadden Arps. But Cellino was clearly frustrated with her and claimed that she openly disparaged him to other lawyers. “When you approached me about having Ellen join the firm you assured me that your relationship with her would not interfere with the management of the firm,” he said in a 2014 email to Barnes. “The same statement was made about your brother. To your brother’s credit he has not interfered with the operation of the firm. The same cannot be said about Ellen.”

For all the talk of absentee leadership and lack of respect, the period after Cellino’s suspension was one of remarkable growth. In 2009, the firm launched a new ad campaign: “When asked which law firm they would hire in the event of an accident involving injury, 4 out of 5 Western New Yorkers chose Cellino & Barnes over all other law firms,” read the copy, followed by a list of recent successes. For Cellino, it drove home how far the firm had come. “Years ago we did not have the assets to flaunt and we tried hard to flaunt those attributes by carefully choosing our words,” he said in an email to Barnes and Ciambella at the time. They were finally living up to their own hype.

The firm had opened a Rochester office in 2000, but now things were really picking up. An office in Melville, on Long Island, came in 2008. Then Garden City. And then the huge move to New York City in 2010. In 2012, the firm bought a new phone number: 800-888-8888. It cost $1.8 million. By 2016, Cellino & Barnes was spending $12.6 million a year on advertising. The next year, the firm bought 45,000 television commercials and 15,000 radio ads a month, according to court filings. There were 600 billboards and bus shelters, too, not to mention the internet marketing. The result was more than 55,000 intake calls a year from prospective clients.

Competitors claim that any firm fielding such a huge volume of calls cannot possibly maximize settlements for every run-of-the-mill client. But Cellino & Barnes developed a structure to efficiently process all the cases and incentivize the lawyers who handled them. Each of the firm’s 60-odd attorneys was basically an independent operator. New attorneys started with a salary but were expected to move quickly to pay based mainly — or entirely — on a percentage of the fees they brought in.

The former Cellino & Barnes attorneys I spoke with generally loved the firm and are proud of their time with it. Many lawyers stayed there for years. The chief motivation was clear: You could make a lot of money. “When I first went in, they didn’t have to sell me. I knew I wanted to work there,” one former staff attorney says. “But they bring out the book showing what everybody made the year before, and you’re like, Holy fuck. These guys are making 300, 400, 700 [thousand dollars]. It’s a pretty unique possibility in the context of a personal-injury law firm.”

The lawyers on staff split up the calendar. On their assigned intake day, they answered all the calls — a lawyer would actually pick up the phone after a quick screen — and basically kept all the cases that happened to come in. They could be valuable; they could be dog shit.

Numbers available for the first nine months of 2015 show that of the nearly 1,900 settlements the firm reached, the median value was just $20,000 — meaning the client would get $13,333 (minus costs) and the firm just $6,666. The more experienced attorneys got a cut of 10 to 20 percent, and the lion’s share of the fees went to the firm. The vast majority of its revenue, 77 percent, came from just 20 percent of the cases. For the top 25 cases, the median settlement was $1 million. Big money comes only from the rare big injuries.

“We would consider a ‘leg off’ case”— in which somebody literally loses a leg in an accident — “to be a valuable case. I’m just using that as an example,” says another former staff attorney. “There could be days when only b.s. slip-and-fall cases come in and you had a bad day on intake, or you could have a day where you get two amazing cases against a corporate defendant. It’s just complete luck who called that day.”

The more time you put in, the more you were likely to make. “It’s a volume business,” the former staff attorney says. “You make however much you want to, really, depending on how hard you want to work.” Some attorneys at Cellino & Barnes were shouldering as many as 200 cases at any given moment, compared to an average of 30 to 70 cases at a more typical personal-injury firm.

Stephen Daniels, a senior research professor at the American Bar Foundation, says there’s a reason firms that advertise take on so many small cases. “You can use that to generate the income to cover your overhead,” he told me. “That’s going to be run-of-the-mill stuff: dog bites, slip and fall, car crash. And that may allow you to then handle some higher-end litigation that’s riskier to do, more expensive to do, but could lead to a much higher award or settlement.” Only a handful of firms operate this way, usually just a couple in each geographic area. “Plaintiffs’ firms never have a long life. It’s a very risky business.”

But despite its eat-what-you-kill ethos, attorneys say Cellino & Barnes was still, weirdly, a genial place. “There’s a lot of Buffalo culture at the firm, where everybody is very nice, very polite, very Canadian,” says one. The firm itself was hyperorganized, with apps for the attorneys and a dedicated team in Buffalo that helps prepare legal drafts. Analytics were plentiful. Competitors, even those who think the firm fails to work cases hard enough, concede that Cellino & Barnes had some very talented lawyers.

But a law firm based almost entirely on advertising is also one that can flirt with the exploitation of vulnerable groups. After all, these clients are people who choose their lawyers based on a television ad or a billboard. As one of the firm’s outside lawyers said in federal court, “Personal-injury clients, not to belittle them, a lot of times they are not the most significant clientele.”

It was something one of the former attorneys worried about a fair amount. “ ‘Cellino & Barnes got me $500,000’ is a little misleading to people who aren’t as educated,” the attorney says. “What I would always say when people would call me and say, ‘Well, that guy got $500,000,’ I’d say, ‘But did you see below his waist? He had no legs.’ ”

In 2012, on top of their $500,000-a-year salaries, Cellino and Barnes each took home $5.4 million. In five years, that doubled. (“An idiotic amount of money for personal-injury attorneys,” says one of the former attorneys.) Barnes has a large lakefront house, and he and Sturm recently purchased the property next door. Barnes’s big indulgences appear to be taking exotic trips to climb mountains and piloting his own plane (he recently upgraded from a propeller plane to a jet). Cellino bought a golf course and began building a family retreat on the shores of Lake Erie. This project has alternately been described in court filings and interviews with me as a “house,” a “summer complex,” and a “Hyannis Port–like compound” with trees imported from Japan.

As their successes mounted, though, Barnes’s ambitions broadened. Discussions began in 2011 about expanding into that litigation idyll of car crashes and 40 percent contingency fees: California. After significant planning, Cellino largely backed out, retaining a nominal part of the business so it could remain under the Cellino & Barnes umbrella. Barnes forged ahead, plowing millions of his own money into the project. The L.A. office opened in early 2014; Oakland and San Diego would follow.

In Cellino’s telling, the next year was the beginning of the end. In October 2015, feeling increasingly pushed out, he asked Ciambella to break down the firm’s revenues by office. He then approached Barnes with the idea of splitting their responsibilities, writing a long, detailed email that sounded not unlike someone who has gathered up the courage to ask for a raise. He proposed a division: Buffalo and Rochester to Cellino, NYC to Barnes. “Buffalo and Rochester are stagnant at best, while NYC is taking off like a rocket ship,” he wrote.

At the end of the note, Cellino hinted at deeper emotional forces at play. “I have about 15 years left of my career,” he wrote. “I feel a need to control my destiny. I have experienced it somewhat in the Golf Course business, but the profits are not there to get excited about. You too have experienced a sense of freedom with your CA operation, and I am sure you enjoy 100 percent control.”

Barnes squelched the idea. “I totally disagree with the concept,” he told the firm’s lawyers in an email. But he was spooked. That December, he emailed Anna Marie Cellino, who apparently didn’t know what her husband had been proposing. “I had a difficult meeting with Ross,” Barnes told her. “During that meeting he told me he wanted a ‘divorce’ from me, and other things that I consider to be less than rational given the fact that the firm is doing better than it ever has.”

Tensions escalated. At one point, the men screamed at each other in the office within earshot of employees. “Why the fuck would you want to fuck this up when we are making 10 million dollars a year?” everyone remembers Barnes yelling. That was especially galling to the staffers, since for years the firm had refused to subsidize their health insurance.

Since 2012, when his daughter Jeanna graduated from law school, Cellino had been pushing for her to join the firm, another idea Barnes dismissed. Cellino swears his pitch to separate wasn’t about his kids. “When the public perceives that I did this for my daughter, that’s not accurate,” he told me emphatically. Still, he found Barnes’s objection ludicrous. Barnes’s brother and companion were firm lawyers, and Cellino’s brother-in-law and nephew were around too — why couldn’t Barnes extend the same consideration to Cellino’s daughter? “There was no succession plan in place with Steve and me,” Cellino told me. “If we both got hit by the proverbial bus, the firm would disappear in a matter of days, frankly. I mean, the lawyers would leave, join another firm, or start their own firm.”

When I asked Barnes about his refusal to hire Cellino’s daughter, his answer was no less mystifying than what he said to Ross himself. “To me, the business model was not one that allowed for that” is all he would say. The explanation that made the most sense to me came from an attorney who knows both men, Marc Panepinto. “Pure conjecture,” he told me, “but I think he feels, ‘I did the right thing by you, bringing you back, but bringing your fucking daughters here to give the firm to them — that’s not going to work for me.’ ”

A couple of weeks after Barnes’s intervention with Anna Marie, Cellino tried again. In a long email, he offered a revised proposal for a split: Allow for Jeanna to come work at the firm, but exclude her salary and bonus — as well as those of family members like Ellen Sturm and Rich Barnes — from the firm’s profit-sharing agreement. “I know you believe this is all about my children,” Cellino told Barnes. “It really is not.” He also proposed that he control all the marketing decisions for the Buffalo office, where a competitor named William Mattar had started to eat away at the business with his own catchy slogan (“Hurt in a car? Call William Mattar”) and a threatening phone number (“444-4444”). Cellino said this was his true reason for action. “The desire to beat him down overwhelms me with daily thoughts.”

Barnes again rejected his partner’s suggestions. The men carried on like this for months. In a March 2016 email (they now seemed to do everything by email, on account of the screaming), Cellino wrote, “You were the one that drove a stake in my soul when you said to me ‘Ross, why the fuck are you quibbling over nickels and dimes when I literally gave you millions of dollars — I did not have to take you back.’ ”

Barnes responded less than an hour later: “As to this bullshit about driving a stake in your soul, you ought to thank your lucky stars that you had and have me as a partner instead of some cocksucker who might have taken a different view of things. And there are a lot of cocksuckers out there, Ross. I didn’t hear you objecting to the way that I was running the place during the 10+ years that by your own admission you were doing nothing.”

The following year, in May 2017, Cellino filed to dissolve the firm. He announced the decision with an email blast to employees: “As you may know, my dad started the predecessor to Cellino & Barnes in 1958,” he started, before listing every iteration of the firm’s name since that time. All but the short-lived Barnes Firm began with Cellino: Cellino & Likoudis; Cellino, Bernstein & Cellino; Cellino, Dwyer & Barnes. He ended by dangling the question of who would become the next Barnes to his Cellino. “Cellino & ???” His follow-up note to staff lawyers was even more explicit: “Please now allow me the opportunity to explain what I believe are our options going forward: you can join my new law firm or join Steve/Daryl.”

Barnes tells me that even now he still can’t quite believe Cellino would do such a thing. “You look at the money and you look at what lawyers make in this country and you look at two jamokes from Buffalo who did not attend the Ivy League,” he says. “And we got ourselves in the position where we were making money that the highest-paid partners of Skadden Arps would be extremely jealous of. Why you would choose, intentionally choose, to blow that apart — that’s why the whole decision was kind of mind-boggling to me.”

Barnes made it clear that he would not let the firm go down without a fight. But to do that, he’d have to both savage his partner in court by saying that Cellino’s complaints were utter fictions and prove that relations between the two men were somehow reconcilable.

As the case progressed, lawyers at the firm weighed in, filing affidavit after affidavit. The papers got very strange. “The office stress is palpable,” one staff lawyer wrote, adding that he hadn’t shown his affidavit to either Cellino or Barnes; he just wanted to tell the court what was happening. “In my view, given the promises from both Ross and Steve, the employees are not worried about their jobs since all have been promised employment, but the tensions between Ross and Steve spill over into the entire office. The rumor mill grinds on a daily basis — Steve bought a new 1-800 number — Ross is filming new commercials for his firm — Steve has rented out his own space and has new computer servers — it goes on and on.”

Like a kind of legal Russian nesting doll, the fight over dissolving the firm gave birth to at least two other lawsuits. First, Anna Marie Cellino, who was an attorney and executive at a natural-gas company, decided to hang out her own shingle as, of course, a personal-injury lawyer. Her partners? Daughters Jeanna and Annmarie. The name? Cellino & Cellino, LLP. A coordinated action to get a jump start on the breakup of Cellino & Barnes? Of course not, they insisted; it was just an opportune time to enter the market. Cellino himself would swear up and down he had absolutely nothing to do with the new firm.

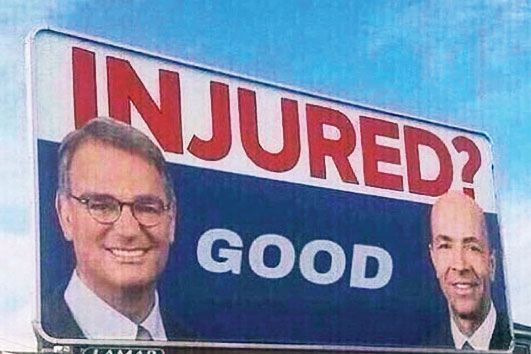

So Cellino & Barnes, PC, filed a federal trademark-infringement lawsuit against Cellino & Cellino, LLP. The Cellino women hadn’t exactly been subtle about the whole thing, launching a radio-ad campaign and putting up at least one billboard. Future plans were even more explicit. Where the classic Cellino & Barnes ad featured the two men on opposite sides of the question “Injured?,” a proof for a planned Cellino & Cellino ad used the phrase “Car Crash?” over a nearly identical backdrop. After Barnes launched his suit, the Cellinos changed their firm’s name to the Law Offices of Anna Marie Cellino. After the name change, Barnes lost and didn’t pursue it further.

Separately, Sturm filed suit against Ross Cellino, saying he had cut her out of her share of settlement fees for a case she and Barnes had litigated together. The case concerned a horrific accident involving a teenager and a fuel called FireGel used in ceramic firepots. When the pot was lit, it led to an explosion; the young man died eight years later after tremendous suffering. The suit, against Bed Bath & Beyond, was eventually settled for what Barnes says was an enormous amount, the largest in the firm’s history. Sturm’s suit accused Cellino of withholding her compensation for it, “in what can only be an act of petty and vindictive retaliation.”

For Barnes, this was a true friendship-breaker. “I didn’t think he needed to do that,” he told me. “And he did it just to — it was the old thing. How do you hurt the man? You go after his woman. That was too much. That created some bad blood, I will admit that.”

The case was set to go to trial in January, but as almost always happens when personal-injury lawyers weigh their prospects in front of a jury, something gave. Barnes told me he asked himself, “Are we actually going to have a trial?” It didn’t make sense. He and Cellino reached a settlement to break up the firm, including a deal on the Sturm case. In September, the famous ads stopped. The jingle went silent. The phone number will soon be mothballed. The two men have agreed not to disparage each other (mostly).

Two firms will take the place of Cellino & Barnes: The Barnes Firm and Cellino Law. The final step before separating was for Cellino and Barnes to make offers to the lawyers they wanted to take with them and for the lawyers to choose sides. Slightly more than half went with Cellino, with most of the upstate lawyers sticking with him and the NYC lawyers with Barnes. Both men see glory days ahead, and each wishes the other great success.

“I think we had a good partnership,” says Cellino. “We got great results for our clients, but I think we can do greater things separated from each other.” After the bruising court battle, Cellino decided to buff his image, taking out billboards and ads of himself next to fuzzy animals to tout his initiatives with the local SPCA. He made a gauzy promo video of himself throwing a football with his grandkids (and occasionally wearing smart-looking glasses with no lenses). Cellino told me he is signing a lease to expand to the Bronx. He even reconciled with Mark Rappold, and the two have lunch sometimes. (David has improved considerably. He can listen to TV and argue and tell his brothers off.)

For his part, Barnes is pleased about his consolidated coast-to-coast operation, and he isn’t worried about competing with his former partner. “I know Ross is going to come out spending a ton of money on advertising, but we both are,” says Barnes. “It’s going to be a bit ridiculous for starters, seeing both of our heads up on billboards separately. But that’s okay. People will get used to it.” Both lawyers have already bought new 1-800 numbers to plaster on billboards. And don’t worry — there will be new jingles, too.

*This article appears in the September 14, 2020, issue of New York Magazine. Subscribe Now!