One year ago this month, the 2020 presidential election was called for Joe Biden, leaving most Democrats elated over the impending end of Donald Trump’s presidency. It hasn’t even been a full year since Democrats achieved what once seemed like an even more impossible dream: seizing trifecta control of the federal government via two victories in Senate runoffs.

But wow, has the sweet taste of victory curdled for the Donkey Party! For months now, it has been rare to read a story about the state of affairs in Washington that did not prominently feature the “Democrats in disarray” trope; the party is said to be divided over the agenda of a president with steadily falling job-approval ratings, doomed to a midterm defeat that might also usher Trump back to the brink of power. From hot takes to data-driven assessments of hard cold electoral facts, everyone pretty much agrees the future for this recently triumphant party is dim, and fingers of blame are being pointed in every direction.

There is one positive thought that Democrats can focus on as we head into this season of hope: This is far from the worst they’ve had it. For all their struggles, Democrats remain the oldest continuously operating political party in the country, dating back to the 1820s. As the comedian Henry Gibson sang in the bicentennial satire film Nashville: “We must be doing something right to last 200 years!”

Here’s a look back at some similarly sticky situations from the Democratic Party’s past, which it managed to survive.

Presidents with bad job-approval ratings

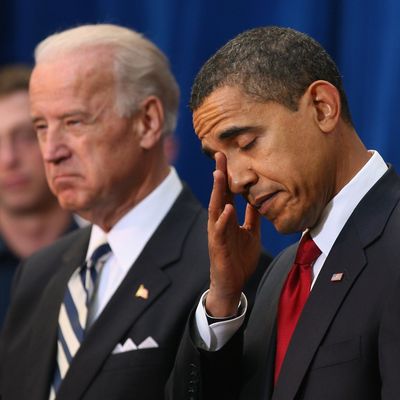

Joe Biden is the seventh Democrat to serve as president since the end of World War II. His current job-approval rating from Gallup is 42 percent. Of the other six, five (all but JFK) had Gallup job-approval ratings quite a bit lower than that. (Truman: 22 percent; LBJ: 35 percent; Carter: 28 percent; Clinton: 37 percent; Obama: 38 percent). Clinton and Obama were reelected after posting these abysmal numbers. And while Truman’s nadir in popularity was achieved near the end of his presidency, he, too, was reelected in 1948 after receiving a job-approval rating of 36 percent in April of that same year.

By these standards, it is extremely premature to treat Biden as a failed president, or as any sort of convincing underdog for reelection, for that matter.

Heavy off-year election losses

The loss of Virginia’s governorship earlier this month combined with a close brush with defeat in New Jersey has been the latest apocalyptic sign of Democratic decline, by some accounts. It’s true that both states were adjudged as “blue” going into these elections. But still, Democrats have done poorly in these off-year elections periodically for a long time.

To be specific, since the late 1960s, Democrats lost the New Jersey gubernatorial race six times (in 1969, 1981, 1993, 1997, 2009, and 2013) and the Virginia gubernatorial race six times (in 1969, 1973, 1977, 1993, 1997, and 2009). Theses state-level defeats were followed by midterms gains for the national party in three cases and losses in five cases. Democratic presidents serving in years when the party lost one or both of these states’ gubernatorial elections were reelected in 1996 and 2010 and defeated in 1980. The point is, there’s no pattern here; off-year election losses are never a good omen, but they aren’t always predictive, either.

A party with ideological divisions

For anyone with a long memory, much less historical knowledge, the idea that Democrats are currently divided ideologically to an unusual or intractable degree is laughable. Today’s centrist-progressive rift existed to an even more alarming extent when Barack Obama was trying to enact his own legislative agenda. In the Clinton administration, conventional liberal Democratic dissent from the presidential agenda was so sharp and regular that the president often got as much or more support from Republicans than from Democrats for initiatives ranging from trade expansion to welfare reform. Clinton’s “New Democrats” (he had originally campaigned as “a different kind of Democrat”) and their orthodox liberal opponents warred constantly until the effort to impeach the president united them.

Going back further, Jimmy Carter had to head off an ideologically inspired reelection primary challenge from “liberal lion” Ted Kennedy. Divisions between pro-administration and antiwar Democrats during LBJ’s second term led to that president’s forced retirement as he faced an almost certain primary defeat, and a convention so intensely divided that the mayor of the host city was shouting anti-Semitic obscenities at a U.S. senator delivering a nominating speech with the whole world watching.

In 1948, Democrats were so divided that not one but two splinter parties (the Progressives under FDR’s second vice-president Henry Wallace, and the Dixiecrats under then-Governor Strom Thurmond) ran candidates against Harry Truman. And going further back, the 103-ballot 1924 Democratic convention nearly flew apart during a vicious fight over a platform plank (which was defeated) condemning the Ku Klux Klan.

A party struggling with economic problems

A lot of the doom-stricken talk right now is about inflation, supply-chain interruptions, and budget deficits, causing a free fall in Democratic support (actually, according to Gallup, the percentage of Americans citing economic problems as the top concern is well below historic averages, but whatever). Today’s economic anxieties are minor compared to those for which Barack Obama was unjustly blamed upon taking office in the midst of the Great Recession.

And neither Biden nor Obama have encountered anything like the horrid combination of economic conditions (double-digit inflation, double-digit interest rates, up-and-down unemployment) that Jimmy Carter inherited from the Nixon and Ford administrations. On running for president, Carter coined the term “misery index” for the combined inflation and unemployment rates — a term that boomeranged when Republicans served it right back at him in 1980.

A party with a vicious and uncompromising opposition

The one thing today’s Democrats can plausibly cite as an unprecedented problem is an opposition party fully devoted to obstruction. But it’s important to remember that today’s chief obstructionist, Mitch McConnell, is the same man whose declared primary goal in 2009 was making Barack Obama a one-term president. After 2010, Obama also had to deal with an intransigent tea-party movement that in turn stiffened the spine of the entire Republican Party.

And even though Bill Clinton worked with and often ran circles around his Republican opponents, he did face after 1994 in House Speaker Newt Gingrich a congressional leader who took partisanship to heretofore unknown levels.

It has largely been forgotten in faulty remembrances of Jimmy Carter’s fecklessness that the New Right and Christian Right movements that arose to smite him hip and thigh were very much the ancestors of yesterday’s tea-party movement and today’s MAGA extremists.

A party facing an unscruplous tyrant

It is true that the task of defeating and ejecting President Donald Trump has put innumerable strains on the Democratic Party — strains that cannot heal so long as a comeback by the tyrant is fully in play.

But once upon a time, a similarly unscrupulous Republican president, Richard Nixon, stood astride a prostrate Donkey Party after winning reelection in 1972 by a 23-point margin, carrying 49 of 50 states. It looked for all the world as though a massive and perhaps irreversible realignment had occurred in favor of the GOP, whose nasty culture-warrior vice-president Spiro Agnew was the heir apparent to Tricky Dick.

But less than two years after their electoral apotheosis, both Agnew and Nixon had resigned in disgrace, leaving Democrats on the brink of a midterm landslide and then a presidential victory.

It’s true that Democrats are prone to self-doubt and pessimism, just as Republicans are prone to triumphalism and spin. But history shows you often don’t know what’s right around the bend.