As you are likely aware, the big challenge for Democrats in Congress this year has been an attempt to pass a bipartisan infrastructure bill and a massive reconciliation bill containing much of President Biden’s agenda, while simultaneously avoiding a debt-ceiling crisis and a government shutdown. The $1 trillion infrastructure bill (which cleared the Senate months ago) finally passed the House and was signed into law on November 15 following a rough agreement on the Build Back Better reconciliation bill. Subsequently, on November 19, the House passed a version of BBB. But with the Senate still yet to act, negotiations on that legislation and other related must-do items continue, with their due dates repeatedly being pushed back. Here are the latest updates on what’s taking so long, when Chuck Schumer and Nancy Pelosi say they’ll wrap things up, and when they actually have to finish to avoid various political and economic disasters.

The Budget Reconciliation Bill

Earlier this year both the Senate and the House passed on strict party-line votes a budget resolution for FY 2022 that authorized a budget reconciliation bill of up to $3.5 trillion. But because any one Senate Democrat or any three House Democrats could sink the legislation by withholding their votes, negotiations over the size and shape of the package have been complex and at times fractious.

After many, many starts and stops, and considerable negotiation between different House Democratic factions and Senate “centrist” holdouts Joe Manchin and Kyrsten Sinema, the White House announced a scaled-back $1.85 trillion version of BBB that could win the requisite number of House Democratic votes for passage. It then cleared the House on November 19 — after an all-night speech by House Minority Leader Kevin McCarthy — with just one House Democrat (Jared Golden of Maine) dissenting.

The bill includes $570 billion to combat climate change; $380 billion for universal pre-kindergarten and child-care subsidies; $190 billion for a one-year extension of the expanded child tax credit provided earlier this year in the stimulus legislation; $305 billion for health care, including a Medicare hearing benefit, new Obamacare subsidies and in-home care for seniors and the disabled; $175 billion to build a million affordable housing units; and $205 billion for a four-week paid family-leave benefit. Left on the chopping room floor were a Medicaid expansion for states that rejected the Affordable Care Act’s earlier expansion, Medicare vision and dental benefits, and free community college.

The new spending would be paid for by a 15 percent minimum tax on large corporations; a one percent tax on corporate stock buybacks; measures to reduce income shifting to overseas subsidiaries of multinational corporations; new surtaxes on millionaires and multimillionaires; a limited prescription-drug price-negotiation program; and stepped-up IRS enforcement. Left out of the revenue package were a much broader prescription-drug price-negotiation system and a repeal of Trump’s corporate and individual income-tax rate cuts.

What’s the holdup?

While House passage of BBB was a huge breakthrough, the bill must still get through the Senate, where Joe Manchin and Kyrsten Sinema have already been instrumental in forcing a shrinkage of the package but haven’t at all signed off on the House version. In particular, Manchin has opposed a family-leave expansion, and Sinema has policed the revenue provisions. Both will likely be troubled by the small but symbolically important budget deficits CBO has suggested the bill will produce. If and when the Senate passes BBB, the final version will then have to get back through the House, potentially upsetting the rickety coalition put together for the House-passed bill.

When do they say it will be done?

No one is making promises about when the Senate will get done with its version of the reconciliation bill, much less when the House will (or won’t) approve the final version, Since negotiations may be slowed down or complicated by the appropriations (and possibly debt limit) issues expected to reach crisis point in early December, we’ll probably soon hear congressional leaders talk about getting everything done by Christmas or, worst case, the end of the year.

What’s the real deadline?

Technically, the budget resolution that authorized the reconciliation bill remains in effect until the end of FY 2022 on September 30, 2022. Democrats could also choose to roll over certain provisions contemplated for the Build Back Better legislation into a new FY 2023 budget resolution and reconciliation bill. But either stratagem runs into the conventional wisdom that Congress never enacts controversial legislation in an election year and the reality that House moderates vulnerable to defeat in 2022 may get even warier of an expensive bill.

Raising the Debt Ceiling

Congress enacted a temporary measure lifting the public-debt limit by $480 billion on October 12. It was anticipated then that the increase would keep the federal government from defaulting on its obligations until at least early December.

What’s the holdup?

As has been the case since at least July, congressional Republicans are insisting that lifting the debt limit is the exclusive responsibility of the Democratic Party as it is (a) the governing party at present and (b) the party proposing trillions in new spending, taxing, and debt. Democrats have logically responded that today’s debt is the product of yesterday’s spending, particularly during the Trump administration, when Democrats were willing to cooperate in raising or suspending the debt limit. Republicans demanded that Democrats include a debt-limit measure in their Democrats-only FY 2022 budget reconciliation bill (a bit difficult insofar as that measure has not yet been drafted), while Democrats demanded that Republicans stop filibustering a simple resolution lifting the limit.

Finally, right as an economically calamitous debt default was becoming a real possibility (Treasury Secretary Janet Yellen had set a deadline of October 18 before its own “emergency” measures to pay the government’s bills would run its course), Mitch McConnell offered to provide enough votes to overcome a filibuster on a temporary debt-limit increase (providing it supplied a specific dollar amount that Republicans could exploit in 2022 attack ads), which is what happened on October 12.

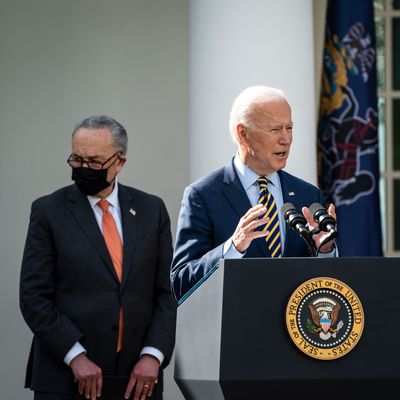

Right after the vote, though, Senate Democratic leader Chuck Schumer made a floor speech blaming the whole contrived mess on Republicans, and an allegedly offended McConnell vowed never to extend Democrats a debt-limit lifeline again.

But then he changed his mind, presumably under pressure from business interests terrified at the prospect of global economic dislocations that might stem from a debt default. To protect Republicans from right-wing backlash, though, in December McConnell devised a two-step process whereby 50 Democrats and at least ten Republicans would support a temporary “fast-track” procedure for a debt limit measure, which Democrats could then pass by a simple majority vote with no help from Republicans. The fast-track bill will be passed first by the House, where Democrats never need Republican support, and then McConnell must just wrangle ten GOP votes for his devious maneuver.

When do they say it will be done?

Both parties agreed the temporary debt-limit increase enacted in October should suffice until mid-December. McConnell’s maneuver, which will be accompanied by lots of yelling and screaming from conservatives in both chambers, is expected to wrap up by the end of the week of December 6. The debt limit increase should take the federal government safely past the 2022 midterm elections.

When is the real deadline?

It’s pretty much whenever Janet Yellen says it is. Experts now estimate there may be enough incoming federal revenues to push the upcoming early December debt-limit cliff to as late as mid-January, delinking it from the government-showdown “cliff,” which would be helpful.

Avoiding a Government Shutdown

On September 30, Congress headed off a government shutdown with a stopgap spending bill extending current appropriations for a bit more than three months. This is a pretty common practice, since regular appropriations are almost never completed by the end of the fiscal year.

When is the deadline?

There was no real ambiguity about this deadline: It fell on December 3, when the stopgap spending authority expired; a new stopgap spending bill was enacted on December 2 that extended current appropriations until February 18, when there could be another shutdown threat.

What’s the holdup?

Democrats wanted a short-term stopgap bill in order to provide just enough time to impose their own priorities on spending. Republicans wanted a longer extension in order to freeze in spending levels set under the Trump administration, They eventually compromised on a February 18 deadline. There was some last-minute drama when Senate conservatives threatened to torpedo the extension by objecting to a unanimous consent motion needed to speed it through; they were demanding a vote on an amendment defunding the Biden administration’s vaccine mandate program. They were given the vote by Chuck Schumer after he became certain the amendment would fail thanks to Republican absences.

Sooner or later, though, there is likely to be conflict over spending levels. Democrats prefer short-term extensions until negotiations over individual appropriations bill can reach fruition. Republicans would prefer an extension till the end of the fiscal year (next September 30). In addition, factions in both parties will likely try to take any spending extension hostage in pursuit of some kind of ransom. Republicans, who have zero leverage over the budget reconciliation process, will probably refuse to support (and in the Senate will actively filibuster) a new spending bill unless Democrats make a concession or concessions on the reconciliation bill. But almost anything could happen, up to and including another government shutdown like the one that shuttered much of the federal government in 2018. That one was over Donald Trump’s insistence on border-wall funding. There’s no deadline on major consequences for ridiculous demands.

This piece has been updated throughout.