On January 30, Kash Patel, the next director of the Federal Bureau of Investigation, went to Capitol Hill to attend to the formality of his Senate confirmation hearing. It’s a measure of how tightly Donald Trump now grips Washington that the author of the book Government Gangsters, which posits the FBI has been controlled by criminals, met with only token resistance. One of the 12 Republicans on the Judiciary Committee, Mike Lee, later posted a video of Patel’s entry into the hearing room scored to the badass opening riff of Metallica’s “Enter Sandman.” The committee’s ten Democrats flailed at him to little effect. Patel dodged and dissembled and occasionally flashed some irritation. When pressed on whether he’d fire agents involved in investigating Trump or open investigations of the president’s opponents, he gave guileless-sounding answers. “I have no interest, no desire, and will not, if confirmed, go backward,” he said in response to a series of pointed questions from Chris Coons, the Delaware Democrat. “There will be no politicization at the FBI; there will be no retributive actions taken.”

Even as Patel spoke, a purge of the FBI was underway. The bureau’s acting director and deputy director, Brian Driscoll and Robert Kissane, respectively, had been given their orders by Emil Bove, one of Trump’s former criminal-defense attorneys and acting deputy attorney general. According to notes later leaked to Senator Dick Durbin, the Illinois Democrat, Bove conveyed to them, “KP wants movement.” That afternoon, according to a former FBI official who was told about the events by participants, Driscoll and Kissane walked around the secure suite on the seventh floor of the J. Edgar Hoover Building where the bureau’s top leaders work. They entered offices along the corridor and delivered word from above: Retire or be fired.

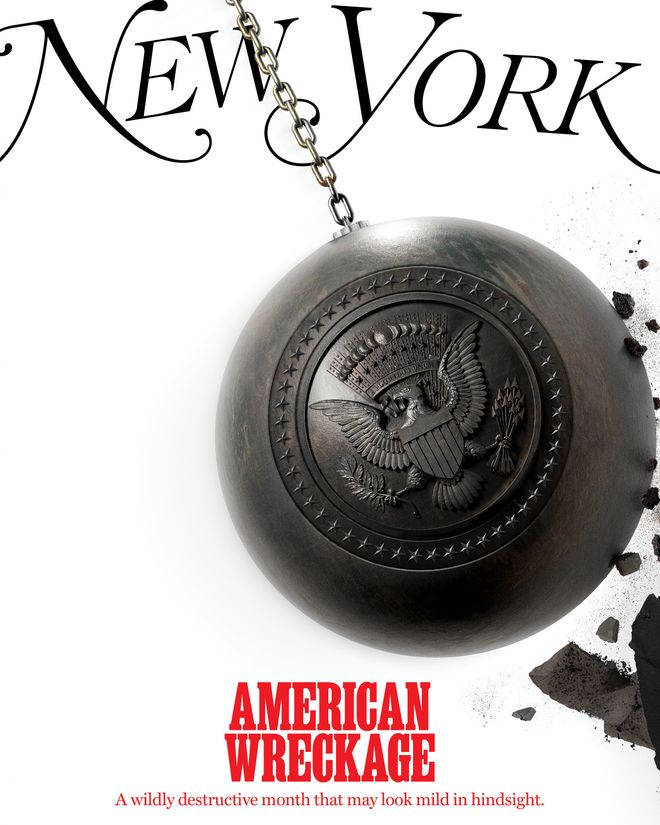

In This Issue: The Purge

Michael Nordwall, the executive assistant director in charge of the criminal branch: Axed. Robert Wells, in charge of the national-security branch: Axed. Ryan Young, the chief of intelligence: Axed. Timothy Dunham, head of HR and acting associate deputy director: Axed. Jacqueline Maguire, who had just taken over the science-and-technology branch: Axed. “They were shocked. Someone walked into their office and said, ‘You’re on the list,’” said the former official, whose account was echoed by two bureau alums who talked with those who were terminated. Bove’s list also included the assistant director in charge of the D.C. field office and two officials accused of retaliation by a group of ousted agents that had testified as whistleblowers before Jim Jordan’s House subcommittee on weaponization. (Patel’s nonprofit had given the ex-agents financial support.) The nation’s internal security service had been effectively decapitated — and a message delivered — while Patel was playing innocent in front of the Senate. “Who are you going to rely on if you whack the whole leadership?” the former official wondered aloud.

During Trump’s first term, Patel, who turns 45 on February 25, worked in a variety of staff roles, distinguishing himself as one of the president’s most energetic knife-fighters inside the national-security bureaucracy. He spent the past four years in Trump’s service as a member of his shadow government, auditioning for his next role by savaging the FBI in books, film, rally speeches, and hundreds of hours of podcast interviews. He declined to be interviewed for this story, but he has already made his intentions very clear, if you were listening. “We’re demolishing the deep state,” Patel told the podcaster Benny Johnson outside the Republican National Convention in Milwaukee. “And we are rebuilding this constitutional republic behind Donald Trump.”

Patel will now take control of an institution with the capacity to surveil, interrogate, and arrest. He will sit in a building named for Hoover, the bureau’s complicated patriarch, who put its powers to political (and sometimes illegal) uses for presidents from Coolidge to Nixon. Since the revelation of Hoover’s abuses in the 1970s, each subsequent director kept a deliberate distance from the presidents he served. But the next FBI director and Trump could not be more closely aligned in their plans, which Patel was more than happy to spell out back when he was just talking to his friends. Government Gangsters includes a now-notorious appendix that names 60 individuals as agents of the “deep state.” “It’s not an enemies list,” Patel said at his confirmation hearing, claiming the appendix was merely meant to be a “glossary.” But that’s not how he spoke when he was promoting the book and campaigning for Trump. “I’m going on a government-gangsters manhunt,” he said in a speech last year at CPAC. “Who’s coming with me?” Trump went so far as to blurb Government Gangsters and called it his “blueprint” for taking back the government.

In an inversion of his party’s traditional reverence of law enforcement, Trump has labeled the bureau a threat to freedom and, maybe more relevantly, his personal liberty. It was the FBI that served a search warrant on Mar-a-Lago related to classified documents. It was the FBI that mounted the largest operation in its history to investigate January 6, one prong of which resulted in the indictment of Trump himself. It was the FBI that investigated Trump much of his first term, beginning with the “Crossfire Hurricane” counterintelligence probe of his 2016 campaign. In Patel’s interpretation of history, it was Trump’s inability to subdue a rebellious government that doomed him in 2020. He “was kneecapped by deep-state rogue actors,” Patel said in an interview for former White House adviser Steve Bannon’s show War Room last year. “That’s the one thing we’ve got to get rid of when President Trump returns to the Oval Office.”

Patel assured his listeners that Trump, once restored, would have a plan to “make sure the government gangsters bend the knee to the Constitution and our way of life in the United States of America.” Patel said the purge at the FBI would start at the top with Director Christopher Wray, the first-term Trump appointee Patel called the “ultimate swamp creature,” and would then chew its way down through the ranks. “You have to remove every person who has violated their oath of office, who has acted unethically, who has discharged their duties in a political fashion,” Patel told Benny Johnson in an interview after the Mar-a-Lago search.

“Maybe it’s time we start raiding these people,” Johnson replied.

So far, the first weeks of the second Trump administration have proceeded very much as Patel said they would. Wray is gone, as is his deputy, who resigned under pressure the day of Trump’s inauguration. The new leadership of the Justice Department, which oversees the FBI, has been clear-cutting its own upper echelon of career officials through terminations, punitive reassignments, and shows of intimidation. Bove’s decision to drop the corruption case against Mayor Eric Adams without even a suggestion of legal justification prompted mass resignations — departures he said he was more than happy to accept. Prosecutors who worked on special counsel Jack Smith’s team and on the prosecutions of the January 6 defendants have been fired or forced out. The new attorney general, Pam Bondi, has formed a Weaponization Working Group to reexamine actions her department and the FBI took under Biden. Bove demanded, and ultimately received, an itemized list of the more than 5,000 FBI agents who worked the January 6 cases.

Since so much so far has gone according to plan, it’s fair to consider seriously whether Patel might do what he has often said he would do if Trump put him in charge. “My top priority would be to investigate the criminality within the government,” he told a podcaster named Mike Adams back in 2022. “I want to know who was involved with that, and I want to prosecute each and every one of those people.” Patel has claimed there was rampant misconduct in the prosecutions of Trump. “Jack Smith,” Patel declared on Johnson’s show this past May, “you should go to prison.”

When confronted with some of his many similarly incendiary statements at his confirmation hearing, Patel snapped that the quotes were “taken out of grotesque context,” and some of his advocates say he should not be judged for things he said back when he was selling books and merch and building his brand as a MAGA crusader. One of Patel’s former superiors in government, the first-term Trump national security adviser Robert O’Brien, told me, “I think Kash is going to be much more of a traditionalist as FBI director than you’d expect.”

The FBI’s tradition, though, includes Hoover, whose example shows how far a director can go. Even after the reforms of the 1970s, the FBI has the capacity to exercise immense coercive power. In addition to enforcing laws, the bureau is also in charge of collecting domestic intelligence — in less polite terms, spying. It sweeps up an enormous amount of private information in the course of its operations, much of which has nothing to do with criminal activity or the people it’s watching. Such secrets can be intoxicating to a certain kind of mind; they can also be used as weapons. Even the most malicious prosecutor can’t invent crimes out of nothing, but it does not take much underlying evidence to open an FBI investigation, and once that happens, a director can order many steps be taken without even asking for a warrant, including the use of surveillance and undercover informants. Those who’ve had their lives turned over by criminal investigations know that, even if charges are never brought, simply becoming a target is enough to destroy your life. Defense lawyers have a saying: The process is the punishment. And the FBI director controls that process.

“I think he’s dangerous in that role,” another former FBI official says. “It’s a uniquely powerful role in our constellation of government. The culture of the bureau is very director-driven and paramilitary. You have access to all kinds of secret information. If you have someone who is willing to leak, willing to say things with a gloss that isn’t true, to open investigations because directed, to close investigations when hinted at or directed to, that is the road to authoritarianism.”

Of course, Patel says that the G-man has it all backward. “They are the criminals,” he wrote in Government Gangsters, “we are the ones who are persecuted.”

He claims he has been fighting his battle against the “deep state” in one way or another since 2017, when he first barged onto the scene as a pugnacious aide to Congressman Devin Nunes during special counsel Robert Mueller’s Russia investigation. “More than anyone in Trump’s first term, Kash came from nowhere,” says Bannon, who talked with Patel continually over the past four years on War Room. Patel shared character traits with many of the people who ascended during the first Trump administration and who are now running the second. He considered himself an outsider. “He was a grinder,” Bannon says. And he was also a climber, even by the standards of Washington, eager to advertise his proximity — and loyalty — to the boss. He says he grew so comfortable in the Oval Office that he was once awakened from a nap there by Trump.

“To have a first-generation Indian American … fall asleep on the couch in the Oval Office — that’s the American Dream, people!” Patel said on the 2022 Fourth of July episode of Johnson’s podcast. Sitting in Johnson’s home studio in Tampa, he cracked open a can of Freedom, a Budweiser special-edition beer, and jammed it into a koozie imprinted with the Punisher logo, the emblem of SEAL Team 6. Bearded and fit, his fatigue-green T-shirt stretched the logo of his personal brand, K$H, tightly across his pecs. His red hat read MAGA in tribute to the big man. “I had to one-up you,” Patel said, taking off the hat to display a familiar Sharpie scrawl on the brim. “Played golf with the boss; got the MAGA hat signed on the 18th green.”

Patel’s father, Pramod, was a refugee, one of the tens of thousands of Ugandans of Indian descent who were labeled “noncitizens” and expelled by the demagogic dictator Idi Amin in 1972. He settled in Garden City, Long Island, where young Kash — whose given name is Kashyap — grew up playing hockey. (He still skates for Washington club team the Dons, which he says is not named for Trump.)

He earned his law degree at Pace University, where he competed with a partner in moot-court tournaments, often surprising teams from more prestigious law schools. After a nine-year stint as a public defender in Miami, where he gathered trial experience while representing drug traffickers and violent criminals and developed what he describes as an enduring suspicion of the games prosecutors can play, he joined the Justice Department in Washington, taking a job as a trial attorney in the National Security Division. Patel worked on terrorism cases, but the highlight of his tenure at the Justice Department, at least as he tells the story, came when he was assigned to work as a legal liaison to the Joint Special Operations Command at the Department of Defense, vetting operations that often involved lethal force.

“Started targeting and killing bad guys with SEAL Team 6,” Patel told Johnson, holding up his koozie. “That was the greatest job: kill, TV, live.” He explained that he would watch on a livestream as the military carried out operations. “The higher-ups would make the calls based on the intelligence, and you would see the chain of command work. And then you’d be like, ‘Oh, that guy’s gone next.’” Someone who collaborated with Patel on terrorism cases says that while he made real contributions, his subsequent descriptions of his work are “somewhat of a fantasy.”

By all accounts, Patel came to feel unwelcome at the Justice Department. He got into scrapes, including a dustup with a cantankerous Texas judge that, though not his fault, ended up being reported in the Washington Post. By 2017, he was ready to go. He has said he was repelled by the way his superiors reacted to Trump’s election. “That place almost imploded,” Patel recalled on the podcast Jack Murphy Live in 2021. “I think some of those actors are still in place, unfortunately. They truly believe they were protecting America from Trump, even though they weren’t, and they were upholding the rule of law, even though they were shattering it.”

Patel went to work for Nunes, who was then the chair of the House Permanent Select Committee on Intelligence and one of Trump’s chief defenders in the Russia investigation. Nunes wanted his committee staffers to conduct a parallel inquiry focused on the FBI. Patel was not in charge, as he has often suggested, but he did play an aggressive role, clashing with members of the Trump administration who got in his way. He reportedly once used his congressional credentials to enter the CIA’s headquarters and tried to personally serve then-Director Mike Pompeo with a subpoena. Patel claims that his demands for FBI records so enraged Rod Rosenstein, the deputy attorney general, that Rosenstein threatened to respond with subpoenas for Patel’s own records and emails. (Rosenstein, who is listed in the appendix in Government Gangsters, denies that this happened: “That’s bullshit. There were four Trump appointees in the room. Nobody threatened to retaliate.”) Years later, Patel would discover that, in fact, he was one of dozens of committee members and staffers whose electronic communications were obtained by the FBI in a leak investigation.

By custom, Capitol Hill staffers are not supposed to get their names in the newspapers — they’re the sources, not the principals — but Patel had a personality that could not be suppressed. He first came to public notice when it was reported that two Nunes aides had shown up unannounced at the London office of the attorney for Christopher Steele, the former British spy whose salacious dossier on Trump was cited as partial support for an FBI surveillance warrant. (Though Patel has exaggerated the committee investigation’s success, claiming it saved Trump’s presidency, he was right about the dossier, which turned out to be garbage.) In October 2017, the Daily Beast identified Patel as one of the congressional sleuths and quoted an anonymous source who described him as “Nunes’s Torquemada.” Patel knew politics could be nasty, but he had never expected the Spanish Inquisition. “My name as a staffer was leaked, which is generally verboten, unheard of,” Patel said in a 2021 interview with the podcast The Grayzone. He has blamed Adam Schiff, then the ranking Democrat on the committee, for the “Torquemada smear.”

Patel does not give up his grudges easily. In Government Gangsters, he says Schiff, now a senator, is “from the inner circle of Dante’s Inferno.” In public conversations, he often refers to Schiff as “watermelon head.” In 2022, Patel published a children’s book called The Plot Against the King in which the villain is a “shifty knight” who is outwitted by a clever wizard named Kash. He published two sequels, the last of which ends with King Donald and the wizard taming the fire-breathing Dragon of Jalapeños, or DoJ, and turning it against cartoon characters modeled on Schiff, Joe Biden, and Kamala Harris. “That guy’s so full of himself,” Patel said of Schiff in 2021. “I’ve been living rent-free in his mind for the last four years.”

Schiff, for his part, has described Patel as an “evil Zelig” because of his habit of popping up in the middle of Trump scandals. His next stop was the National Security Council, where he arrived just in time to play a walk-on role in the internal upheaval that led to Trump’s first impeachment.

Nunes had lost his committee chairmanship after the 2018 midterms, and he lobbied Trump to take on Patel, whose investigative work was done. But John Bolton, the national security adviser, didn’t want to hire a Nunes flunky and resisted, giving Patel a job dealing with organizations like the United Nations, far from where Patel had hoped to be: the counterterrorism directorate. (Bolton, who is on Patel’s list, opposed his FBI nomination, likening him to Stalin’s secret-police chief Lavrentiy Beria.) Patel worked in the Eisenhower Executive Office Building and wore a green badge, which did not grant him entry to the West Wing. He still had never met Trump. But somehow he ended up getting invitedto the Oval Office. “Trump took a real liking to him,” says a former colleague, who told me that Sean Hannity made the connection. Patel offered validation to Trump’s suspicions that the FBI, the DoJ, and the intelligence community were out to get him. Unlike others on the staff, Patel didn’t try to manage the boss. “He actually followed the president’s instructions,” the former colleague said. “He responded directly to the president’s questions and interests.”

Some National Security Council colleagues suspected Patel might be serving as a back channel between Trump and characters like Rudy Giuliani, who had been snooping around for compromising information about Joe Biden in Ukraine. Fiona Hill, a senior Russia expert, later testified that she had heard Trump was under the impression that Patel was running Ukraine policy. (Patel has denied speaking to Trump about Ukraine; Hill is also on his list.) In the summer of 2019, a CIA analyst who had been detailed to the White House filed a whistleblower complaint revealing the phone call in which Trump made his arms-for-Biden-dirt proposal to President Volodymyr Zelenskyy. (An individual who Patel says is the whistleblower is identified by name on the list.)

That August, around the time the White House learned of the whistleblower, deputy national security adviser Charles Kupperman was summoned to the Oval Office. He says he was surprised to find that his subordinate, Patel, was waiting for him there with the president. “Someone had planted the idea with the president that there were a lot of ‘unloyal’ people in the White House and ‘unloyal’ people in the National Security Council,” Kupperman recalls. He says Trump proposed to “expand Kash’s portfolio” and make him “basically political commissar.” Kupperman scotched the idea. (He is on Patel’s list.)

Trump survived the impeachment, and Patel’s status continued to rise in the White House. He moved into counterterrorism and visited the Oval Office with unusual frequency for someone at his level. By convention, NSC staffers are not dispatched into the field, but Patel took on special missions, such as a trip to Damascus to meet directly with Bashar al-Assad’s intelligence chief about the missing American journalist Austin Tice. “A lot of the senior policy officials don’t want to deal with the hostage world,” says O’Brien, who replaced Bolton as national security adviser. “Kash was willing to break glass.” Patel taped organizational charts of Al Qaeda and ISIS leaders to the wall of his office, and each time a member of either group was killed, he used one of Trump’s Sharpies to X out a face.

Patel hopped from job to job within the national-security bureaucracy, mixing it up and making new enemies. In the counterterrorism directorate, he annoyed Defense Secretary Mark Esper, who booted him from the Situation Room during the raid that killed the leader of ISIS. Trump then sent him to the office of the director of national intelligence, where he fought to declassify politically useful documents related to the Russia investigation. In spring 2020, Trump tried to persuade Attorney General William Barr to install Patel as deputy director of the FBI, an idea that showed a “shocking detachment from reality,” Barr wrote in his memoir. He said it would happen over his dead body. CIA director Gina Haspel threatened to resign when the White House attempted to force her to take on Patel as her own deputy. Patel later wrote that Haspel had tried to get him fired. According to CNN, the CIA made a criminal referral to the Justice Department in 2020 alleging Patel circulated classified Russia-related documents to unauthorized parties. (Patel was not charged; Esper, Barr, and Haspel are all on the list.)

That November, six days after the election, Patel was with Trump in the Oval Office when the president fired Esper in a tweet. An acting Defense secretary was installed, and Patel went to the Pentagon as his chief of staff. In his memoir, The Melting Point, the now-retired Marine general Kenneth F. McKenzie Jr. described this postelection period as “the time of the sorcerer’s apprentices.” He had the impression that Patel was the one in control. (McKenzie is on the list, though his name is misspelled.) The apprentices clashed with General Mark Milley, the chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff, as they attempted to implement increasingly erratic directives from Trump. (Milley is on the list, and Patel has proposed that he be court-martialed.)

The tensions inside the Pentagon came to a head when a violent mob stormed the Capitol. In a deposition given to the congressional January 6 committee, Patel testified that a few days beforehand, Trump had told him to expect unrest and had authorized the mobilization of 10,000-to-20,000 National Guard troops nationwide. But they were not deployed, a lapse Patel blames on Washington’s mayor, Democratic congressional leaders, and the generals, who reportedly didn’t like the optics of having the electoral certification take place inside a Capitol surrounded by the military. Patel spent January 6 working inside the Defense secretary’s suite, fielding calls from members of Congress and the White House as troops were mobilized to restore order.

“I remember seeing Kash in the hall,” says Ezra Cohen, who was acting undersecretary for intelligence and security at the time. “He was not happy. He told me he was pissed that the National Guard, the army, and Milley didn’t have their act together.”

After January 6, many of those who had worked alongside Patel at the White House offered their resignations. Patel never distanced himself. Instead, he would side with the extremists, endorsing their counternarrative of victimization by the FBI. “There was no insurrection,” Patel said this past October on War Room. “They ginned it up.”

Really, his friends say, Patel had no choice but to stick with the boss. Someone exiting a presidential administration at his level would traditionally expect to find a high-paying landing spot: maybe a partnership at a K Street law firm or a sinecure position at an investment bank. But those options “were foreclosed to him,” says Alexander Gray, who worked with Patel on the National Security Council staff. “The swamp was trying to do everything it could do to purge people who were associated with Trump.” So Patel joined the government-in-exile.

“Kash bet correctly that Trump wasn’t going away when others were deserting him left and right,” says Bannon. “He passed up career opportunities over the past four years to be available to fight the weaponization war.” Patel started to spend time in Florida, where Trump was stewing over 2020, floating ideas about “terminating” election laws and the Constitution, and playing a lot of golf. (Patel has told a story about how Trump tried to help him fix his wicked slice.) He involved himself in Trump’s priorities, such as the launch of Truth Social — which reunited him with Nunes, now the chief executive of the platform’s parent company — and a fight with the National Archives over classified documents, which would once again lead to disaster.

Up to this point, Patel had spent his whole career in the public sector. Now he made his living from a consulting firm, which billed Trump’s social-media company and political-action committee. He started to do podcast interviews from his Washington condominium, where he would appear in front of a carved-wood American flag. Patel soon discovered that, as a former national security official, he could speak with particular credibility to grassroots audiences. They were hungry for information from inside the deep state.

Clay Clark, an Oklahoma promoter, invited Patel to join the speaker roster for ReAwaken America, his traveling political festival, which featured stars of the fringe like General Michael Flynn and pillow peddler Mike Lindell. Patel impressed Clark with his willingness to do free-form Q&A sessions with crowds. “That’s as close as you can get to raw and unfiltered,” Clark says. “He said, ‘I want to hear from people.’” He was fine with wading into the craziness.

Through Clark, Patel met a lot more podcasters, and he went on shows like Patriot Street Fighter, where he listened politely as the host told him “the Khazarian Mafia” — referencing an antisemitic conspiracy theory — has been in “full control of the planet.” He was introduced to the QAnon folks, who already knew him by reputation. (“Kashyap Patel — name to remember,” Q had posted in 2018.) At his confirmation hearing, Patel said he “rejected outright QAnon baseless conspiracy theories,” but he appeared on shows hosted by QAnon adherents. He promoted his books and merch and told them that while he did not subscribe to all their beliefs, he respected the “dominant following” of their movement. “I think people are having fun with Q,” he said on one podcast. “You’ve got to harness that following that Q has garnered and just sort of tweak it a little bit.”

Patel was building his own following within the MAGA movement. He created a brand, Fight With Kash, and started a company called Based Apparel. He plastered his K$H symbol on shirts, hoodies, hats, scarves, socks, thermoses, flags, and wine. Proceeds from the merch, he told audiences, went to a nonprofit called the Kash Foundation, which he originally set up to bring defamation lawsuits against news organizations. “I’m going to help Americans have their day in court so they can exact a revenge against the mainstream media,” he told Bannon on War Room. Patel personally sued Politico, the New York Times, and CNN over various news reports about him, as well as a social-media troll over a post that called him a “Russian asset.” (The lawsuits against the new organizations were dropped or dismissed; the troll case has been dormant since last August.)

Over time, the Kash Foundation expanded its mission, giving grants to families of defendants in the January 6 cases. He contended that the Justice Department’s probe was a massive overreaction that had swept up many innocent Americans. He theorized that undercover FBI “instigators” were responsible for provoking the attack. “How many people have been arrested and detained in the D.C. jails based on that entrapment?” Patel asked on his podcast, Kash’s Corner, in 2023. That year, he helped to produce “Justice for All,” a benefit recording of a choir of inmates in the D.C. jail singing the national anthem, which he promoted on War Room and other podcasts. Patel said at the time that he was “intimately involved” and boasted that it had gone to “No. 1 on Billboard, literally ahead of Miley Cyrus and Taylor Swift,” although at his confirmation hearing, he would claim to know little about either the single or the choir.

“I’ve never, ever, accepted violence against law enforcement,” Patel told Adam Schiff.

“Oh, no, you didn’t accept it,” Schiff replied sarcastically. “You glorified it in song, Mr. Patel.”

It was easy to knock the hustle, but fame was the currency of Trumpworld, and Patel was accruing capital. He moved to the swing state of Nevada and started to give speeches at Republican campaign rallies. He leveraged status as a MAGA celebrity into substantial wealth. Patel’s ethics disclosures indicate he made around $2 million last year from his consulting firm. (Besides Trump, its clients have included a Czech arms manufacturer, the government of Qatar, and the parent company of the Chinese fast-fashion retailer Shein, which granted him stock worth at least $1 million that will vest when it goes public.) He made hundreds of thousands more from his podcast and books with promotional help from the boss.

Some of the people named in the appendix to Government Gangsters say they have no idea why they are on his list. Many are well known, but there are some who served at relatively low levels, including current and former FBI agents. “I’m not calling for any sort of harm to them physically,” Patel said on Kash’s Corner. But he has said on many occasions that he hopes for legal punishment. “Of course, we have to win in 2024 and send Donald Trump back to the White House so we can clean house of these government gangsters,” Patel told Roger Stone, who was convicted during the Russia investigation and later pardoned by Trump, on his show The Stone Zone in 2023. “Then we come back and we prosecute every single one of them for continuing the criminal conspiracy that they started from Russiagate.”

Patel was right about one thing: The FBI was still after Trump. In March 2022, the bureau secretly opened an investigation, code-named “Arctic Frost,” into Trump’s attempts to overturn the results of the 2020 election. Later that year, Trump’s long-brewing struggle with the National Archives over presidential records he was refusing to return culminated in the FBI raid on Mar-a-Lago. Patel had involved himself in the dispute, publicly contending Trump had declassified a “mountain of documents” on his way out of the White House, which seemed to provide him an alibi. According to a redacted summary of an interview with Jack Smith’s prosecutors, one adviser to Trump described an individual who matches Patel’s description as “unhinged” and “crazy” and said he had no idea what he was talking about. Patel was hauled before a grand jury, where he gave undisclosed testimony under a grant of immunity.

The day before Trump was arraigned on 37 felony counts in the case, Patel appeared on Donald Trump Jr.’s podcast and proposed to close the Hoover Building and disperse thousands of agents from headquarters to field offices. “Reopen it the next day as a museum of the deep state, and let every American walk the halls for free to know how the FBI rigged presidential elections and robbed us of justice,” Patel said. “You need 25 folks in D.C. to run the FBI.”

There have always been people who wanted to blow up the FBI: civil libertarians like Supreme Court Justice Felix Frankfurter in the early days; the post-Watergate reformers; the September 11 Commission, which questioned whether the bureau should be broken up and stripped of its domestic-intelligence function. The agency has always come through its crises in one piece. It is easy to criticize the FBI from the outside, its defenders say, until you get the clearances and see the secrets. Its most compelling argument for preservation, now as ever, is that it saves lives.

Every man appointed to be FBI director since Hoover has been a Republican, and all have come into the job with years of high-level law-enforcement experience. Patel, by contrast, seems to have only one important qualification. “Kash Patel has a very inflated view of his history and capabilities, and his basic motivation is fealty to Trump,” says Kupperman. Daniel Goldman, a former Manhattan federal prosecutor and Ukraine impeachment committee counsel who is now in Congress, says Patel “has shown that he does not care about rules, he does not care about laws, he does not care about ethical standards. In this position, he will have a tremendous amount of power to potentially execute his own stated intentions to politicize the FBI, as well as Donald Trump’s stated intentions to go after his political enemies.” (Patel once called for Goldman to be criminally investigated over a tweet he didn’t like.)

The idea of nominating Patel to be FBI director went from right-wing fever dream to political reality in the mad scramble of the early transition. Patel spent the final days of the campaign on a Team Trump bus tour through Pennsylvania and flew down to Florida. On Election Night, he and his girlfriend, a country singer and young conservative activist named Alexis Wilkins, attended a party for members of Trump’s inner circle in the Mar-a-Lago ballroom. By the next morning, he was back on War Room, wearing a MAKE AMERICA BASED AGAIN T-shirt and starting to sound like a candidate. “At the end of the day, I don’t have a revenge list,” Patel said. “I want the Constitution applied uniformly.” Some of the more moderate voices in the transition opposed Patel, arguing he was “immature and needlessly provocative,” according to an adviser who was involved, but Trump was in a bullish mood and decided to throw the long bomb.

“When President Trump named Kash Patel, a lot of people laughed and said he had a snowball’s chance in hell,” says Mike Davis, the president of the Article III Project, a harsh critic of the FBI and Justice Department. The temperature quickly changed. The grassroots activist base that Patel had been talking to for four years rallied around his nomination. His confirmation battle turned out to not be much of a fight at all. He lost only two Republicans. His allies are now relishing what comes next. “The FBI ran a political operation on the former president, and unfortunately for the FBI, he is now the president again,” says Davis. “There is going to be hell to pay, and there should be.”

Patel’s new employees are currently in a state of anxiety, wondering how high the price will be. The round of terminations the day of his confirmation hearing cleared out the seventh floor of the Hoover Building, and his first full day on the job brought news of 1,500 Washington employees being relocated, but so far, the bulk of the bureau’s workforce, which numbers around 38,000 people, have been in limbo as they wait to find out what is in store. The bureau is full of conservative, patriotic former soldiers and cops, which makes Patel’s contention that it has been infiltrated by Democratic sympathizers sound all the more ridiculous to insiders. Andrew McCabe, the former FBI deputy director who was fired by Trump over his role in the Russia investigation — and later investigated, cleared of wrongdoing, and awarded his pension — told me he had lately been talking to his former colleagues, “many of whom I haven’t had contact with in quite a few years. I think a lot of people are finding themselves in a situation where they’re thinking, Oh my God, I spent my life working for this country, and now I have to start figuring out how to protect myself against it.”

In the interregnum between Trump’s inauguration and Patel’s confirmation, the rank and file rallied around the acting leaders, Driscoll and Kissane, a pair of veteran agents who were brought in from outside Washington without much apparent advance consideration. Kissane, the senior man, was supposed to be acting director, but when a White House announcement mixed the two men up, Driscoll, a mustachioed former hostage-rescue team commander known as Drizz, ended up in the top job. Word spread among their fellow agents that Drizz was fighting the Justice Department over its requests for names of the agents who worked on January 6, even though, as an agent who had yet to reach the vesting age for his pension, he could not afford to simply walk away from his job. Drizz wrote a message to the staff defending the January 6 investigators, noting, “I am one of those employees.” Bove fired off a memo, accusing the acting leaders of insubordination. Drizz fans within the bureau forwarded attaboys and “What Would Drizz Do?” memes.

“Unless he comes in with something new, Kash’s vision that he articulated to this point is ‘I’m going to burn the place down,’” says Christopher O’Leary, who served until 2023 as a section chief in the counterterrorism division in Washington. “They’ve used corrosive tactics, which is no way to motivate and inspire. It may scare a few people into following you, but for the most part, it’s going to make people put their heads down.” O’Leary pointed out that any purge of the January 6 case agents would disproportionately hit counterterrorism teams because they were assigned to go after the rioters. (Bove has said that “no agent who carried out their duties in an ethical manner” will be fired.)

Patel has articulated some substantive proposals for structural reforms. Government Gangsters contains several incongruously wonky chapters that read like they’re coming from a former public defender. He says he wants greater transparency and increased safeguards for civil liberties at the Foreign Intelligence Surveillance Court, which authorizes the FBI to secretly intercept electronic communications. His critique of the head count at headquarters, around 7,000 employees, is widely shared among those who have worked at the bureau, even if they don’t think the answer is to turn the building into a museum. (Patel claims the proposal was hyperbolic but he’s serious about redeploying resources — as the reported 1,500 relocations attest. “You’re cops — go be cops,” he says.) Some of Patel’s advocates, like Bannon, suggest he’ll revive the old idea of breaking the bureau into different agencies that handle law enforcement and intelligence. It remains to be seen, however, how strong Patel’s desire for a smaller bureau, and his commitment to civil liberties, will remain once he’s at the controls.

Those who have served under past directors find it hard to fathom that Patel could disrupt the bureau as much as he may imagine. He has never been the head of anything of any size, and it is a huge, obdurate organization filled with people who are skilled at withholding information, misdirection, and other tactics of bureaucratic resistance. Agents are taught to pay meticulous attention to legal niceties. The culture is cautious. Even the January 6 and classified-documents cases, which were thoroughly predicated, proceeded at a deliberate pace, as agents worried — correctly, as it turned out — about political blowback. But in Patel, Trump picked a director who will take his phone calls and respond to his interests, and it is not hard to guess what he will want next.

Trump may end up disappointed. “Can he push charges or pursue investigations against people where there really is no articulable basis for a charge? The answer is ‘not likely,’” says Daniel Richman, a former federal prosecutor and Columbia University professor who was an adviser to former FBI director James Comey. “One of the cool things about America is we have statutes that have elements to them. You can’t just make up crimes.” But that does not mean Trump won’t order Patel to look for political crimes, whether they exist or not.

“I’m not suggesting that the majority of FBI agents would support these efforts,” says McCabe. “You don’t need to convince all of them that this is a good idea. You just need a few to do it.”

Patel has theorized that once he clears out the disloyal, cooperators in the government will offer incriminating information about the deep state. In a podcast appearance from the living room of his rented home in Las Vegas in September, Patel told Sebastian Gorka, the right-wing academic and media personality, that the DoJ and FBI could employ the same tactics they used to “build big RICO cases,” promising favorable treatment to informants. “We take people and flip them, and we turn them against the operatives we are chasing down,” Patel told Gorka, now a National Security Council staffer. “There’s many ways to do it, but these tools are already in the tool kit. We just have to turn out the DoJ and the FBI, make that a priority, to have internal accountability.”

“I can think of somebody,” Gorka said, “who could lead those investigations and prosecutions.”

Trump had the same idea, and now the Senate has confirmed Patel for a ten-year term — a duration established back in the 1970s as a safeguard, on the presumption that a director who served multiple presidents would not become too subservient to one. Trump has different expectations, and he has found his man, for now. After the confirmation vote, the president’s deputy chief of staff, Dan Scavino, posted a photo of a grinning Trump holding up Patel’s newly signed commission and a Sharpie. On Friday morning, Patel went to work on the Hoover Building’s seventh floor. Later in the day, he was sworn in by Bondi at the White House, where he praised Trump as a “courageous warrior.” He also sent a statement to his employees, promising he would “have your backs” and committing to “rebuild the American people’s trust in the FBI” through “full transparency” and “rigorous obedience to the Constitution and a single standard of justice for all.” It sounded reassuring on the surface, until you asked, Whose standard? Trump has shown he is willing to fire an FBI director who doesn’t follow his directions. The real test comes when the phone rings.