It is a dirty secret (or maybe a clean one) that this generation of grown-ups, seeking a postmillennial, futuristic level of hygiene, has decided that toilet paper is Not Enough. Anecdotally, the baby-wipes-for-adults trend appears to have begun with young moms who got the idea at the changing table, but it’s prevalent enough to have made its way to the population as a whole. In 2007, the actor Terrence Howard vehemently suggested that women without a box of wipes in the bathroom were “just unclean.” Will.i.am offered a similar opinion a couple of years later: “Get some chocolate, wipe it on a wooden floor, and then try to get it up with some dry towels. You’re going to get chocolate in the cracks. That’s why you gotta get them baby wipes.”

This lavatory preference is a clandestine one, an activity that people don’t like to admit to. That much was proven in the early aughts, when Kimberly-Clark and Procter & Gamble each introduced a premoistened-toilet-paper-on-a-roll product. (The product that P&G introduced had initially borne the unfortunate name Moist Mates.) They both tanked, most likely because they were highly visible: The plastic-enclosed roll fit into your bathroom’s toilet-paper dispenser, making your hygiene practices explicit to every visitor, and perhaps making them wonder whether you had some unlucky medical condition.

The solution was for manufacturers to offer wipes that were packaged for adults, marketed as an adjunct to rather than a replacement for conventional toilet paper. This approach has been much more successful, creating a new, eager, aloe-slicked market. Charmin Freshmates are positioned as “flushable wet wipes [that] provide a cleaner clean than dry bath tissue alone. When two things are so good together, why keep them apart? Pair your Charmin toilet paper with Charmin Freshmates to feel fresh and clean.”

The razors-by-mail company Dollar Shave Club just introduced a line called One Wipe Charlies, aimed at younger men. (From the bro-toned promotional video: “Reach around for a deeper clean.”) DSC’s co-founder Michael Dubin says that his market research revealed that “51 percent of guys are using wipes regularly alongside TP, and 16 percent of guys were using wipes exclusively. That blew our minds. Less surprising, but equally compelling, was that 24 percent of guys hide their wipes from view, the No. 1 reason being they’re embarrassed.” Cottonelle is in the same game, with its Fresh Care line of “flushable cleansing cloths.”

The key word in that pitch is flushable. It means, broadly, that a wipe probably won’t clog your pipes on the way out of your house, but it doesn’t mean it will break down. A recent Consumer Reports test, performed with a lab stirrer in a neatly simulated toilet, revealed that a sheet of toilet paper falls apart after about eight seconds in swirling water; a putatively flushable wipe didn’t so much as fray after half an hour. (Or, as one beclogged D.C. homeowner phrased it on a parents’ message board, “The cost per sheet of flushable wipe is $1—meaning for every flushable wipe, $.10 is for the wipe, and $.90 goes to the plumber.”) A few websites posit that aging cast-iron pipes, as opposed to new PVC, are likelier to have rough interior surfaces that cause snagging.

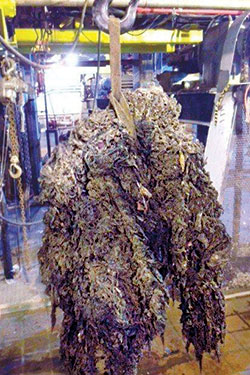

The real trouble, though, occurs downstream, explains Carter Strickland, commissioner of the New York City Department of Environmental Protection. “You can safely say [it’s costing us] millions of dollars,” he says. (An aide of his offers a ballpark figure of about $18 million per year for extra disposal, and that doesn’t include staff overtime and damaged equipment.) Even if a wipe does not get stuck in your toilet, or your house’s sewer pipe, or even the big conduits under the street, it eventually ends up at the treatment plant, where it’s joined by all its viscose and rayon kin. Lately, the screens where foreign matter is filtered out of wastewater are absolutely choking on these things. “We’ve gone from about 50,000 cubic yards a month to more than 100,000 cubic yards a month” of debris, Strickland says, and that’s just since 2008. The Wards Island treatment plant seems to be getting the worst of it, but all around the city, huge gray-black masses of synthetic fiber, steeped in every foul fluid that’s gone down the drain, are regularly being extracted, by hand, from pipes and pumps. Jammed, snarled equipment frequently breaks down, causing “a lot of downtime.”

Other municipalities report similar messes, from New Jersey to Washington State. A big city can survive a lot of things, from blackouts to terrorism, but a working wastewater system is nonnegotiable, and all these wipes are, extremely literally, clogging up the works.

Theoretically, wipe-makers should be able to solve this problem with a flushable product that degrades quickly, and Strickland says that his department has been talking with the INDA, the nonwoven-fabric-industry trade group, about a pending set of industrywide standards for flushability. There are national discussions going on, too, through the federal National Association of Clean Water Agencies and other groups, and the NYCDEP is looking to legislate what can and can’t be labeled flushable. (Dollar Shave Club’s Dubin is quick to say that his One Wipe Charlies “meet industry qualifications for flushability. Plus you should only need one, hence the name.”)

The basic problem, however, is that toilet paper is specifically engineered to come apart in water. It is inherently fragile. A wet wipe, by contrast, is supposed to be tough enough to hold up under a constant soaking in its water and propylene glycol lotion, and under the mechanical pressure of scrubbing. It is, as Strickland puts it, “very, very strong, pound for pound, like spiderweb.” (The technical term for the most common material is spunlace.) In short, the very thing that makes a wet wipe good at its job makes it a problem once it’s discarded.

At least we’re not quite as bad off as London, with its Victorian sewers. This summer, the British press went nuts writing about a fifteen-ton blob of cooking grease, bound together with fibrous material from wet wipes, that was discovered under the streets of the Borough of Kingston Upon Thames. It was the size of a city bus. It quickly became known as the “fatberg,” and had almost completely stopped up an eight-foot-diameter pipe, threatening to flood the whole neighborhood. “The wipes break down and collect on joints and then the fat congeals,” explained a representative from Thames Water to the Guardian. “Then more fat builds up. It’s getting worse. More wet wipes are being used and flushed.”

He’s right. Wet-wipe consumption overall has nearly tripled in the past decade, according to Kimberly-Clark figures. It’s overspilled the baby-products aisle, too: You can buy dedicated wood wipes, stainless-steel wipes, leather-furniture wipes, computer-screen wipes. All of which are arguably wasteful but not especially harmful—unless you put them down the drain.

For Strickland, the issue comes down to education. “We just have to equate it with diapers,” he says. “No one would flush a diaper down the toilet. I hope.”

Have good intel? Send tips to [email protected].