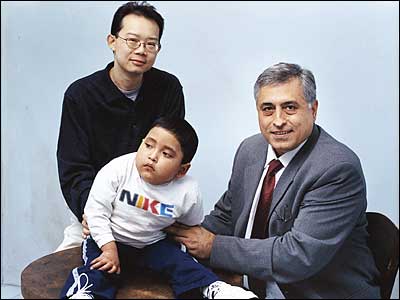

Medical Miracle #10Problem: Two adults and a child, each with failing livers, each requiring a transplant. Can one organ save all three?

Doctor: Sukru Emre

Patients: John Lee, Harriet Goldman, Franklin Chuqui

For John Lee, Harriet Goldman, and Franklin Chuqui—three strangers, each with a different rare liver disease—February 6, 2005, figured to be a miserable Super Bowl Sunday. All three were in desperate need of new livers. “For them,” says their doctor, Sukru Emre, head of the adult and pediatric liver-transplant programs at Mount Sinai Medical Center, “there was no other chance but a transplant.”

Lee, 37, was confined to his home in Flushing, unable to summon the energy to go out. A missing enzyme in his liver had caused the onset of familial amyloid polyneuropathy—a genetic disorder that contributed to his mother’s death. Like Alzheimer’s disease, FAP slowly damages nerve endings. In Lee, this was causing shooting pain in his hands and feet, as well as fainting spells and acute diarrhea. He’d lost 50 pounds, dropping to 102 pounds on a five-foot-seven-inch frame, and he was depressed. Without a transplant, he could expect to live for no more than five to ten more years, Emre says, and his symptoms would only become more debilitating.

The 67-year-old Goldman had gone through advanced cirrhosis once before (the cause was unknown; she doesn’t drink), and had spent “eleven wonderful years” with her transplanted liver before it, too, began to fail. As she sat at home in Suffern, New York, with her husband and friends, the toxic products her liver should have been cleansing from her blood were contaminating it instead. Her energy was sapped, her mind clouded. “There was practically nothing I could do,” she says. “I was like a car without gas. I was running on fumes.”

Chuqui, just 5 years old, was the sickest of them all. Like Lee, he was missing an enzyme, only in his case his blood was becoming acidic. He would go into seizures, or “metabolic strokes,” slump to one side, and become nonresponsive. He always recovered, but not without suffering some degree of brain damage. Most of Chuqui’s short life had been spent between hospitals and rehabilitation centers. That night, he was in the hospital again. Then, during the third quarter of the football game, Emre got a call that would save all three patients’ lives.

A young woman had been in a car accident in Vermont, and the United Network for Organ Sharing, a national nonprofit group, was calling to offer her liver to Chuqui (with livers in extremely short supply—2,000 people died last year waiting for transplants—the organs are distributed on a priority basis). Because the donor liver was too big for Chuqui’s tiny body, Emre could perform a “split-liver transplant,” giving a smaller piece of the liver to the child and the rest to an adult. What’s more, Mount Sinai could choose the adult. “John was always on my mind,” says Emre.

As it happened, Lee’s rare FAP liver was also suitable for a “domino” transplant—the transfer of a whole liver from a living person who is in turn receiving a liver transplant himself. Lee’s enzyme disorder had not damaged his liver per se. The organ metabolized food, produced bile, and detoxified the blood just as any healthy liver would do. It also, of course, caused his FAP and its attendant symptoms, but only over the course of 30 years. Goldman was grateful to take her chances with it. “If I’m lucky enough to live to be 100, I’ll deal with it then,” she says. “As far as I’m concerned, the liver is perfect.”

Before dawn that Monday, Emre pulled together three teams of surgeons for a rare split liver–domino combination transplant. Emre set up three connected ORs, each with a different patient and its own set of surgeons, with Emre orchestrating the three procedures. Chuqui and Lee were opened up at the same time, around 1:30 P.M. While Chuqui was receiving his small portion of the split liver, doctors examined Lee’s liver to be certain it was healthy enough for Goldman. As doctors in the first room completed Chuqui’s split-liver transplant and sewed him up, doctors in the second room removed Lee’s liver, and doctors in the third room opened up Goldman. The large piece of the split liver went directly into Lee at the same time as Lee’s liver went directly from his body into Goldman’s. The next day, Lee and Goldman were wheeled into the same recovery room, both still groggy from anesthesia. “We waved at each other,” Lee says. “She said, ‘I think you saved my life.’ ”

It’s not known how much long-term damage Chuqui suffered, but he rarely has seizures anymore. He can talk, move around, and watch TV. He recognizes and responds to his parents better than ever.

Lee is reveling in small pleasures, like climbing a flight of stairs, opening a bottle of water, or driving to the supermarket to pick up groceries by himself. He has also become active in the national Amyloidosis Support Network. The pain in his hands and feet hasn’t abated—and it will never be gone entirely—but he’s not as winded or dizzy, or depressed anymore. “I think a lot of weight is off my chest. I feel hopeful that I’m at the bottom of the roller-coaster ride and the only way to go is up.”

As for Goldman, she had a recent episode of rejection, but having been through this once before, she’s staying calm. “Your body has to acclimate to a new organ. I don’t know if I told you, but we’re expecting our eleventh grandchild. I’m confident I’ll be around to see him.”