Until the day David Wong was framed for murder, his life was of little interest, even to him. It had been, as Wong would later say, a “stupid” life, “just wandering around like a zombie.” By about 14, he’d dropped out of school in his native China. At 18, he was illegally shipped to New York by his worried mother. There, she hoped, his father, a Chinatown restaurant worker, would straighten him out. For a few weeks, Wong’s father secured him a bunk in a crowded rooming house (which the son had rights to when no one else claimed it). Then Wong was on his own. He drifted from job to job, making a few friends, though not the right kind. In 1983, at the suggestion of one friend, Wong got involved in an armed robbery. He didn’t make it to the scene of the crime—he spoke no English and so had trouble deciphering traffic signs. Still, the police, alerted in advance, found him nearby with a gun in his pocket. Wong never heard from his friend again. And his father, ashamed, shut him out as well. Convicted of armed robbery, he became New York State inmate No. 84-A-5320, sentenced to eight years, and was sent off to Dannemora, a maximum-security prison built into the side of a mountain in upstate New York.

Wong’s first years in prison were as uneventful as the rest of his life up to that point. Then, on the afternoon of March 12, 1986, Wong, crew-cut, 135 pounds, stood by himself in the prison yard, reading an out-of-date Chinese newspaper. A light, late-season snow covered the ground. He pulled the hood of his green state-issue sweatshirt over his head against the chill, just like many of the other 600 inmates in the yard that day.

At a few minutes past four, an inmate later said, “a real quietness fell over the whole area.” Suddenly, one hooded inmate circled behind another and, as a guard 120 yards away later reported, delivered a blow to the back of his neck with a knife fashioned from a soup ladle. The guard lifted his binoculars and picked out the person he believed to be the culprit. In a prison report, he said the stabber “appeared to be white.” Later he’d say the murderer was an “Oriental.” There were two “Orientals” in Dannemora. The guard identified the killer as David Wong.

A day or so later, another prison guard summoned an inmate, a convicted forger. Had he seen the stabber? the guard asked.

“Black guy,” offered the inmate, who, like the guard, was white. He played the odds. Most inmates were black.

“Wasn’t it an Oriental?” The guard showed him Wong’s photo.

“Okay, yeah, it was,” the inmate said and made a deal to testify against Wong.

Wong was convicted again, this time for murder, one he didn’t commit. The year was 1987. Wong was sentenced to 25 years to life, an event, he’d later suggest, that was about to begin his life all over again. The conviction was, as he put it, “a blessing.”

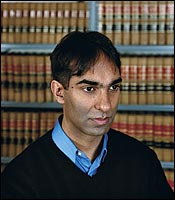

A dozen years later, a young attorney named Jaykumar Menon began his first job at the Center for Constitutional Rights on lower Broadway. He stepped over duct tape covering tears in the carpet, pushed through a door bearing an Amadou Diallo poster, and soon put his legal mind, such as it was, to work on the case of David Wong.

An illegal immigrant who drifts from one inconsequential job to another, who commits small-time, even brutish, crimes, attracts little sympathy. But someone wrongly convicted—that person becomes a rallying point, a cause. By then, Wong had become a symbol of a corrupt court system—his appointed translator hadn’t even spoken his dialect—and, for some, a convenient place to stash disappointment and anger. In legal circles, his case became notorious—fourteen able lawyers had worked on it over the past decade, including William Kunstler.

Some sympathizers even put Wong on a pedestal; some developed a stake in what they imagined to be his sense of grievance, in what they were sure must be his unhappiness. In the process, inconvenient biographical details got reworked—that armed robbery had been an attempt, it was now occasionally said, to help a wrongly fired friend recoup back wages.

For Menon, Wong didn’t have the particularities of a real person; he’d never met him. Menon is a large, mocha-skinned man with a shaggy head of black hair who strikes friends, as one put it, as an “irretrievable dreamer.” He aspired, he sometimes said, to lead an interesting life, a cloudy desire that had initially led him to the Internet. Before practicing law, Menon had helped start an Internet marketing company. It was successful, and yet how long could a person seeking an interesting life go on about a terrific new “e-commerce solution”? “I want to do justice,” Menon had almost shouted at his interviewer at the Center for Constitutional Rights, before landing the $42,000-a-year job.

And so perhaps Menon could be forgiven if he perceived in David Wong an opportunity, just the kind he was looking for. “The case is nowhere,” he told himself. “So why don’t we just swing for the fences?” Over the years, Wong’s lawyers had made a barrage of filings on the murder conviction, to which the courts had been uniformly unreceptive. And so, propelled, it seemed, by his own enthusiasm, Menon had another thought, a grand one. “Why don’t we find out who the real killer is?” he wondered. Menon, for the moment, put aside the fact that he’d never had a law client before; Wong was to be his first. In fact, Menon soon did the calculation: The afternoon of the murder, he’d been a suburban high-school student running a slow leg in a mile relay. As he later explained, “I had no experience. Not even one year. None.”

In the years immediately following his murder conviction, David Wong had been an angry man, not that many people noticed. He still couldn’t speak much English and refused to try to speak to white people at all. “I knew not all the white people was bad,” says Wong, “but they do what they want to do.” Prison, though, proved a place of self-invention. First it was Islam. Wong became a convert and took a Muslim name—the name David had been pinned on him when someone couldn’t manage his real name, Kin Chin Wong. Then Wong decided to learn English, and next, the law. “That’s the only way I can fight back,” he said. Soon, Chinese-English dictionary in hand, he was coaching others in the prison law library and espousing a peculiar, prison-bred optimism. “Human being, even bad ones,” he said, “in some situations do good.”

Menon recalls his initial encounter with his first client. Wong had summoned Menon, his fifteenth and, by far, least-experienced attorney, to prison. There Wong, says Menon, was “ripping the legal choices, every one of them.” Menon searched for responses. He didn’t have many because, as he puts it, “Wong knew more about criminal law than I did.” Menon didn’t dare reveal that he was incubating a bold new strategy—to find the real killer. After all, he didn’t yet have anything to show for it.

As Wong’s motions had limped through the court system, rejection following rejection, Wong began to attract a following. People he’d never met declared themselves moved by his circumstances and volunteered to help. The David Wong Support Committee first convened in 1991. Of the dozen members, many were Asian, a unifying thread. Still, the intensity of commitment seemed perplexing. Was the abstract notion of injustice that stirring? It couldn’t have been Wong, an abstraction himself, nor fellow-feeling, since none of the original committee members had met one another (or Wong). Usually, only celebrities, radicals get defense committees. “Who was David Wong?” wondered one attendee, and answered his own question. “A nobody.”

Even some of the members were baffled by the committee’s persistence. “I’m usually a quitter,” says longtime member Patti Choy, 51, a career counselor at the Fashion Institute of Technology. Yet the committee became a community, a group that seemed involved in more than proving Wong’s innocence. Two members married; seven members, inspired by the case, became lawyers. Declares Wayne Lum, a postal worker and the committee’s chief strategist, “This is my life.” Patti and her husband, Guy Kudo, who don’t have children, got to know Wong and incorporated him into their family. Perhaps Wong, with his slim biography, his inaccessibility, could be whatever people wanted: an innocent, a sage, a role model, or, to Patti, a long-lost friend. More than most, she came to respect and to love Wong. “He’s on my mind 24/7,” says Patti. “I feel like he’s been taken away from us. I just miss him.”

Menon’s partner in freeing Wong was a private investigator named Joe Barry, perhaps the only one in the city without law-enforcement experience. “Every P.I. in New York is an ex-something,” says Barry. “I’m an ex-nothing.”

For the most part, Barry seems content to make himself up as he goes along, largely along film-noir lines, which, inevitably, makes him a pariah in certain circles. A lot of lawyers don’t like him. “I can’t stand the guy,” says one. He’s been fired from almost every job he’s ever held. “Fourteen or fifteen,” Barry guesses, shrugging his slender shoulders.

Barry says he likes to figure things out for himself. “I have my own methods and my own ways,” he says. Barry’s guide in his life, as in his work, is his savior, Jesus Christ. As far as formal training, Barry’s is in Bible studies. He’d once hoped to earn a living as a teacher of New Testament Greek, a dead language that he, inexplicably, could read fluently. Unfortunately, Barry had his own view of certain religious matters, like the Holy Trinity. The seminary decided he should go his own way.

“I don’t have time to waste,” says Barry about that turn of events. For a time, he led church services in his home. (These days he attends “church” in someone else’s house, and, as the Bible commands, donates a tenth of his income to it.)

Barry’s idiosyncrasies didn’t exactly endear him to Menon’s colleagues at the center. There was, in addition to everything else, the zone of secrecy he maintained around his activities. He refused, for instance, to open an office or provide a home address. “I have several locations I operate secretly out of,” he told employers. “I operate like a ghost. I’m the man with no name and and no address.” If this dramatic flourish was intended to impress, it didn’t do the trick.

“Give me a break,” responded one of Menon’s colleagues, exasperated. “Like he’s Mister Private Eye.”

More frustrating still was Barry’s attitude toward report-writing. “I don’t write reports,” Barry says. Once in a while, he’d present handwritten documents, a page or so of block letters resembling a ransom note.

Still, if Barry was a professional oddball, as marginal in his way as David Wong, there was also something irresistible about him. Lawyers have a duty (and a financial interest) to vigorously defend all comers. Barry, inspired, as he put it, by “my upbringing in the Bible,” wanted good deeds to do. “Dirtbags,” Barry calls guilty defendants. As earnest in a sense as Menon, he preferred innocent clients, and in the past fifteen years, he had gotten a dozen of them out of jail.

In considering Barry’s continued employment, Menon and his colleagues noted that past investigators hadn’t made very much progress. Barry, at least, seemed intent. The Bible admonishes a person to seek the truth; Barry’s business card declared him “Dedicated to the truth.” “If you want the truth, you have to go get it,” he says, “and it’s going to be hard to get.” Barry, though, was prepared to make Menon a promise. “If there are people out there that know Wong didn’t do this, dead or alive, I promise to find them,” said Barry, who, for good measure, added, “and if they’re alive I’ll talk to them.” For the time being, he was kept on.

Barry took several months to familiarize himself with the record in the Wong case—in addition to low overhead, Barry favors reasonable hours—though it didn’t take long to realize that no one had ever done a thorough investigation. Previous investigators had approached the matter professionally. They generated polite letters requesting witness interviews. The file duly noted that no one responded.

Barry’s technique, by contrast, was “the show-up,” which, as he explained to Menon, involved confronting an unsuspecting witness wherever he could be found. Barry had stories about show-ups in hospital rooms and at workplaces. Once he got going on the Wong case, he pulled a show-up at a golf course. Arriving between holes, he confronted the guard who’d coaxed the inmate to name Wong.

“You forced this guy to say David Wong was the chimp who did this crime, didn’t you?” Barry shouted at the guard, who, presumably, had a club in his hands.

You know,” Wong wrote to a friend, “I have no concept before I come to prison that if I suffer or have pains, others willfeel pains and suffer with me.

Barry turned off a lot of people. Menon, though, decided Barry was a trip and didn’t mind chauffeuring him to the occasional show-up, which was handy since Barry doesn’t drive.

On one car ride, Barry, who dyes his hair (recently bronze), wore oversize sunglasses, which made him striking though not imposing. At nearly six feet tall, he weighs barely 125 pounds. To compensate, he carries a gun, tucked snugly in his pants.

In the car, Barry let Menon know that his Bible and his gun were his twin pillars. “This is law, and this is order” was how he once put it, pointing to his Bible and then to his sidearm. In a minute, Barry launched into a lecture about his gun, a .380 semiautomatic Beretta, which, mid-lecture, he drew from his pants and waved around the car, freaking out Menon.

“Dude, pleeease, we’re driving in a small car,” said Menon, the son of a respectable midwestern cardiologist. “Put that thing away.”

Eventually, Barry uncovered the East Rochester phone number of the inmate who testified that he saw Wong do the killing. Peter Dellfava, part-time roofer, part-time forger, and onetime prison escapee, had been paroled on his first application, a result, in part, of his agreement to testify against Wong. (The district attorney had recommended parole.) Lately, Dellfava was unemployed.

Barry called to make sure “the body,” as he calls the subject, was at the address. In his work, Barry prefers to employ a ruse, which he pronounces rooce. “I’m an honest person,” he says. “Will I lie to get results? You bet.”

Barry phoned, and a man answered. “Is Diane there?” Barry asked. Dellfava’s wife was Diane.

“No,” said the man.

“I got a call from somebody looking for a job,” said Barry.

“I’m looking for a job.”

“Who are you?”

“Peter Dellfava.”

Barry showed up at the small house the following evening, a Saturday, arriving at nine o’clock. A woman opened the door. Barry glimpsed a burly man lying on the couch. “Get off my property,” said the man, quickly coming to the door. “You’ve got three seconds.”

“Peter,” said Barry, taking a chance, “I need to speak to you about David Wong.”

Dellfava let out a long breath. It had been fourteen years since the murder. “That man did not deserve to go to jail for murder,” he told Barry there on the porch.

Then Dellfava, as Barry put it, “spilled his guts.” He’d gotten cornered by a prison guard. The guard, said Dellfava, “just kind of told me how to make up this story.” So Dellfava tried to work it. “Whatever way I could … ,” he explained, “to get the hell out of [Dannemora].” Wong had been the nearest villain.

Why had he finally confessed to Barry? “Would you want to live with this?” asked Dellfava.

It turned out that many inmates who’d been in the yard at Dannemora the afternoon of the murder knew the real killer’s identity. As one prisoner later said, “I think the whole facility except the administration knew that … David Wong was framed.” Another inmate whispered the name of the killer to Barry, but refused to testify. Then Barry learned that the killer was dead.

Barry visited Otilio Serrano, a kidnapper and armed robber, in Great Meadow Correctional Facility in 2001, using his special approach: He showed up unannounced. At first, Serrano didn’t want to say the killer’s name. Then Barry convinced him the guy was dead.

And so Serrano said that Nelson Gutierrez “come up behind this other individual and stabbed him in the back … I believe it was in the neck.” Gutierrez was a New York City Dominican nicknamed Chino—apparently someone thought he looked Chinese. Perhaps no one had particularly wanted to frame David Wong. Maybe it was a case of mistaken identity, and Wong, a convenient culprit whose English made it difficult to defend himself, happened to be the mistake. Who really cared? He was a nobody.

“Every day,” says Barry, “I thank the Lord for showing me what is true.”

Through his years in prison, David Wong longed for freedom, of course. And yet his past didn’t make freedom seem particularly desirable. He once tried to call up a happy memory of life in America before prison. “In Chinatown,” he managed, “[I] could walk around.”

Now he discovered that a life in prison is still a life. When he checked inside himself, to his surprise he found something other than outrage. “I happy,” he told Patti. “I don’t feel bitter.” Ever since being framed for murder, he’d run into so many strangers with open hearts, people who stirred his emotions and connected him to the world in a way he hadn’t been previously. “You know,” he wrote to Patti and Guy, “I have no concept before I come to prison that if I suffer or have pains, others will feel pains and suffer with me.” He knew it now.

Every two weeks, Wong purchased 50 stamps. He’d write two or three letters some days, typed with perfect margins on his prized possession, a typewriter. (By hand, he added smiley faces to indicate when he was kidding, in case his language didn’t hit the mark.) He’d write Patti and Guy as often as a couple of times a week, seven- or ten-page single-spaced letters, sometimes as soon as they left after a visit. (And he’d call them to make sure they got home safe.) He wanted to discuss everything, every detail of what each said to the other. He talked to Patti about whether she and her husband should buy a new TV and about commitment in marriage. Wong had carefully made a few friends in prison, but nothing like this. “I got to think if I tell them”—prison friends—“something maybe they will take it wrong way,” says Wong. Not Patti or Guy. “We able to talk about everything,” he told Patti gleefully.

Patti came to think of Wong as “a sage,” even a “role model.” How could he go through all this and not let it bother him? She worried about him constantly, and told him so. “He’s a big chunk of my life in New York,” she says. In response, he chided her, telling her not to worry so much, though, he added, “it makes me feel good and happy,” apparently an unfamiliar combination for him.

Menon sometimes suspected that Wong might actually be indifferent to the outcome of the campaign mounted on his behalf. “He didn’t care so much about victory,” Menon once remarked. “He cared that people cared.” And so, though injustice was arbitrary, an evil, Wong seemed at times to embrace it. “Even though the incident unpleasing at the time, it turned out as a blessing,” he told Patti and Guy, “because [it] give me you guys, my best friends, through it.”

In April 2003, Judge Timothy Lawliss, a family-court judge in Clinton County, which includes Dannemora, heard the new evidence in the Wong case, Wong’s best hope to overturn his verdict.

To lead the defense, Menon had recruited William Hellerstein, a Brooklyn Law School professor and Legal Aid alumnus sure of his own talents—“five-and-oh in arguments before the Supreme Court,” he points out.

On the stand, Dellfava admitted that he’d concocted his earlier testimony. He had to “make what I did wrong right,” he said. Nine inmates, five of them murderers, testified that they, too, were moved by Wong’s plight. One talked of a “moral obligation,” as if he too wanted to do justice. Six inmates testified they saw the stabbing. Three named Gutierrez as the killer. One of Wong’s final witnesses was a muscular, broad-shouldered black man, Umar Abdul El Aziz.

On the stand, Aziz started to cry. “You know, me, I’m guilty,” said Aziz. “I’ve committed crimes … I’ll probably die in the penitentiary. Here’s a guy”—he motioned to Wong—“that I know beyond a doubt did not do what … you’re accusing him of doing. He’s been seventeen years in jail trying to get to this point, just to be heard, and man, that’s mind-boggling.”

Judge Lawliss was not moved. What was Wong to him? Another of an endless number of inmates who streamed through upstate courts because they had been wronged. He seemed to know in advance what to expect from this case. Lawliss had been educated in the field. His uncle had retired from the Corrections Department, and Lawliss joked that his father, a former Clinton County sheriff, had ninetysomething first cousins, many of whom had probably worked for the prisons. Wong’s side made an issue of Lawliss’s background—he was also a former law partner of the prosecutor—during the case, but the judge scoffed. Every local official should have a prison connection. Prison employees are among the area’s most potent voting blocs.

In his opinion, Lawliss seemed mystified that anyone could, for an instant, believe such a frightening band of criminals as those who testified for Wong. He dismissed Aziz’s tears as an “attempt to bolster his credibility.” Dellfava’s “demeanor wreaked [sic] of insincerity,” he wrote. Instead, he cited the seventeen-year-old testimony of the prison guard, virtually the state’s only remaining witness, who saw the crime from a football field away. “Any individual who works in the correctional facility would have to understand the significance and enormous responsibility of identifying another human being as a murderer,” wrote Lawliss. Wong seemed inconsequential. If anyone was innocent, it was the guards, Lawliss seemed to say, as if they were on trial, which perhaps they were. If you believed Wong’s new evidence, then unscrupulous prison guards were the real culprits.

Jaykumar Menon’s walk-up apartment in the East Village is tiny—one small room with a kitchen beside another small room with a bed and desk. (His shoes are stored in a bucket under the desk.) Lately, as he knew, his Columbia Law School classmates are approaching partner at prestigious firms. Menon, on the other hand, loads debt onto credit cards. He’d stopped working full-time at the Center for Constitutional Rights, taken short-term legal jobs, and through it all, kept a promise to Wong. He’d taken the Wong case with him. He was in his fifth year with the case. His kitchen cabinets were filled with Wong documents.

“You know I didn’t choose Wong,” Menon says suddenly. He sits at his desk in jeans, his shirt untucked as usual. “I just showed up,” he says, seeming discouraged. Which is true. He’d set out blithely. This was to be a grand adventure. Maybe it’s a kind of moral vanity, this arch-justice-doing. Lately, he occasionally felt as if he’d passed up his whole life to prove Wong’s innocence. “Everybody else is living a regular life, and I’m here on this solitary and secret mission,” he says. He couldn’t go to a movie or commit to anything silly or frivolous without working himself up, telling himself, “Well you know, let [Wong] hang. I’m going to go have fun.”

After Lawliss rejected a new trial, the nightmares started. In them, the stout, square-faced district attorney approaches, grabs Menon’s hand. He’s dropping the charges. “It’s a great feeling, and I’m smiling,” Menon says. The feeling doesn’t last. “I realize that I’m dreaming and it isn’t true,” he says. His stomach tenses. He awakens with a start and reaches for the bottle of pink Pepto-Bismol that sits by his bed.

Most lawyers give a case their best shot, then move on. In the Wong case, fourteen lawyers had come and gone. But what if you believed the client innocent? It’s a lot of weight, thought Menon. There was one last perfunctory appeal to make. Hellerstein canceled classes and worked on a brief. Appeals courts usually respect a lower judge’s evaluation of the facts.

In the Wong case, the appeals court swiftly rebuked Lawliss. Even a prisoner has a right to be innocent, the court seemed to say, and it overturned the guilty verdict. After almost two decades, Wong was granted a new trial. Unfortunately, the appeals court directed Lawliss, who seemed to have made up his mind about the case, to conduct the trial.

Lawliss appeared happy to oblige. On November 1, 2004, Lawliss instructed that jury selection begin in an impossibly short four weeks. No one could prepare for a trial that quickly.

Hellerstein returned to the appeals court and urged it to disqualify the judge, who seemed to know in advance what to think of David Wong. Perhaps Lawliss’s heart wasn’t really in it. He’d stuck with it long enough. Rebuked once by the higher court, Lawliss flinched and recused himself.

The next judge on the case, this one from outside the county, reasonably told the parties that he didn’t see the sense of a new trial. On December 10, the district attorney filed a motion to dismiss the charges “in the interests of justice,” almost as in Menon’s dream.

Late in December, David Wong was freed from the New York State prison system that had been his home for twenty years. He was promptly shipped to a Homeland Security detention facility down the road from a Comfort Inn outside Buffalo—he’s an illegal immigrant; there’s been a standing deportation order in his case since 1994.

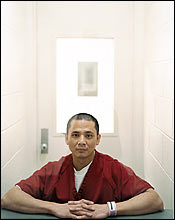

One afternoon last month, he sits in a narrow, bright-white visitor’s room of cinder blocks, his hands folded on a table. He’s been given a new outfit, this one fire-engine red and a little too big. Wong, now 42, could have left prison at the age of 28. He’s become an adult in prison, and culturally American. He’s eager to talk, though in a language all his own. There’s a base of prison-learned English—“I got nobody in China no more”—mixed with bureaucratic terms—“pertaining,” “paperwork”—and an extensive legal vocabulary (in Latin). “The habeas,” he says, or, combining prison shorthand and legal Latin, simply, “the hae.” All of it is dosed with a thick Chinese accent.

Wong stays almost perfectly still, except that his head ticks back and forth a fraction, a calibrated motion that seems to suggest his next thought. “My freedom clock is ticking,” he says. He seems proud of his phrase. His thumbs twirl. He tries to envision life outside prison, something he has been doing a lot of lately. There are basic questions he still can’t answer. Where will he go? What will he do? He can’t seem to picture life outside prison in any detailed way. Will he find a job as a porter, a dishwasher, picking up where he left off? At times, he even imagines himself a translator. Wong says he will be happy to be free anywhere, though, secretly, he hopes that he’d be able to spend time with Patti and Guy in Brooklyn. It’s what Patti imagines, too. “If he gets out, he’s taken care of,” she says.

In all likelihood, as Wong knows, his future will be played out elsewhere. Menon had thought to oppose the deportation order and recruited an immigration attorney, initially a member of the support committee. Little can be done. If China agrees, Wong is headed back to his native village, where he no longer knows anyone. His father is dead. His mother lives far away, in Hong Kong. Patti and Guy, Menon, and the others will be even farther away. Innocence, the longed-for state, has reshaped everything, and yet at this, his valedictory moment, his happiness seems incomplete. From the detention center, his letters begin to change. They are handwritten, less conversational, and for the first time, extensively emotional.

“I am longing and dreaming to have the opportunities to be in you guys’ company,” he writes to Patti and Guy. It’s a simple pleasure he’s rarely had. He’s been with Patti a few hours perhaps, and that’s cumulatively over a decade and, as he points out, with “those guards around controlling where to sit what time we can be together.” Now what he wants most is “to be hanging with my great wonderful friends, having funs and laughters and alls,” as he tells Patti. Funs and laughters and all, this is what he’d imagined as the fruits of innocence.

Patti, too, feels the loss. It is like the loss of a loved one. She too had imagined a different ending. Wong has been good for her, taught her to be more accepting, less judgmental. “I don’t want to think about deportation.” Neither does Menon, though, dreamer that he is, he vows to keep Wong in his life, even if he has to travel to China.

And so, finally, Wong, who has been the luckiest of people, the inconsequential man others rallied around, thinks about deportation. He’s always been the most realistic of this tight group, and now he thinks realistically for Patti and Menon, for all of them. He makes a forlorn promise: “No circumstance and no distance can diminish my fondness at you and friendship to you.” Which is to say, he’s free.