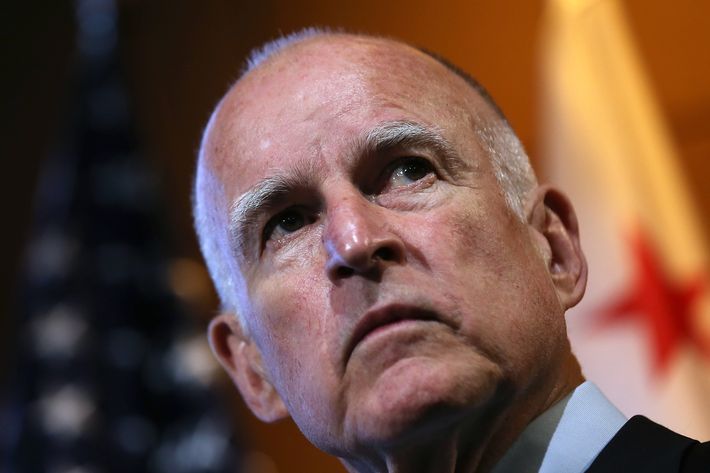

The Democratic Party has built what looks like a stable and demographically expanding national electoral majority. But coalitions can come unglued, and eventually, all of them do, when their policies fail or their elected officials push them too far from the center of public opinion. If you want to see glimmerings of this future unraveling of the Democratic coalition, look where the future is so often found: in California. There Governor Jerry Brown has recently signed an “affirmative consent law,” which requires all sexual activity among college students to obtain “affirmative, conscious, and voluntary agreement” and requires such consent be “ongoing throughout a sexual activity.” It is a massive broadening of the legal definition of rape, and a new blow in the culture wars that will likely reverberate in ways liberals have barely begun to contemplate.

Critics like Michelle Goldberg, Batya Ungar-Sargon, and Cathy Young have questioned the practicality of this new standard. “Do moans count as consent?” writes Goldberg, “How about a nod, or a smile, or meaningful eye contact? If a woman performs oral sex on a man without asking him first, and if he simply lies back and lets her, has she, by the law’s definition, assaulted him?”

The law’s defenders have made some interesting counterarguments. But these, in turn, merely underscore the vast distance between the law’s aspiration and its realistic prospects. “Confirming consent leads to much hotter sex,” writes my colleague Ann Friedman, who suggests various ways that continuous affirmation could be given without killing the mood, “We’re still deprogramming the idea that nice girls don’t admit they like sex, let alone talk about how they like it.”

Tara Culp-Ressler, arguing along similar lines, proposes that the law is “about broadly reorienting about how we approach sex in the first place … The current societal script on sex assumes that passivity and silence — essentially, the ‘lack of a no’ — means it’s okay to proceed.”

It surely is possible to imagine that sex that comports with these new guidelines is sexy, or even more sexy than the kind most people have now. Yet one might find these ideas about reimagining sex attractive, as I do, while still having deep reservations about codifying them into law. The fact that we need to change cultural attitudes about sex itself underscores the fact that cultural attitudes about sex lie well outside the contours established by the state of California. What percentage of the last decade worth of Hollywood sex scenes, if acted out between college students in California, would technically constitute rape? A majority? Ninety percent?

Deprogramming and reorienting societal ideas about sex is an evolutionary process. California isn’t merely attempting to set out to nudge the culture in this direction. It is reclassifying all sex that falls outside those still-novel ideas as rape. A law premised on this sort of sweeping, wholesale change is likely to fail.

Indeed, the law’s advocates don’t uniformly believe its written standards will actually be followed at all. This defense by Amanda Marcotte is telling: “The law has no bearing on the vast majority of sexual encounters. It only applies when a student files a sexual assault complaint.” So the law will not come into play because nobody will actually try to enforce it. Instead, it will technically deem a large proportion of sexual encounters to be rape, but prosecutors will only enforce it if there is an accusation. And since most, and possibly nearly all, sexual encounters will legally be rape, then accusation will almost automatically result in conviction.

Indeed, this may be the point. Culp-Ressler dismisses concerns about convictions of innocent people. (“In reality, false rape allegations are very rare, comprising about two to eight percent of all reports.”) Two to 8 percent seems like a fairly high number of innocent people to convict as rapists, and of course that proportion could well rise quite a bit under a legal regime that expands the definition of rape in ways that are both extremely broad and extremely confusing.

Obviously, failing to convict a guilty rapist is bad, too. There is no downside-free resolution that would avoid unfairness one way or another.

But people have certain intuitive beliefs about justice. If most college students today do not think that sex without continuous, affirmative consent is actually rape, and there is a law in place rendering it as such, soon enough, somebody is going to be prosecuted under these terms. And that person will become a victim of a standard of justice that offends the moral sensibilities of a large number of Americans, which is directly attributable to the actions of California’s elected Democratic officials. What will the law’s defenders do then?