It was unremittingly hot at the farm in Natick, Massachusetts, where 1,500 people had gathered on the Sunday after the Fourth of July. Remarkably, this crowd had assembled under a blistering sun not for a free concert, or outdoor theater, or even a protest, exactly. They’d come for an open-air town hall with their sitting senator, a 69-year-old woman widely expected to win reelection to her second term this fall. Standing at the back of the sweaty throng, I’d seen her introduced from the stage, then heard cheers greeting her entrance, but couldn’t for the life of me lay eyes on her. Not until I climbed onto the seat of my folding chair in the press section. There she was, jogging 75 yards down a hill in open-toed mules, her aqua cardigan flying behind her.

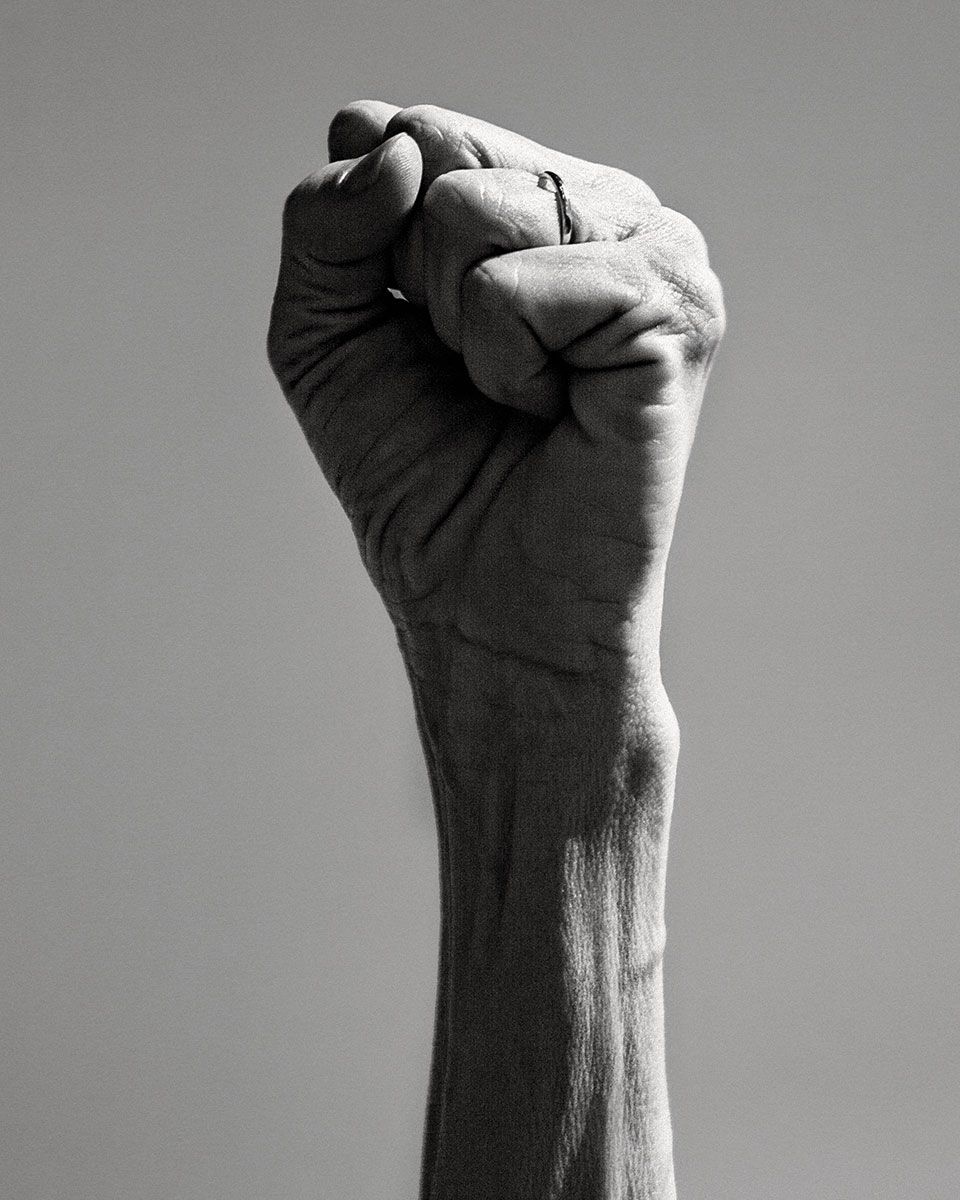

Massachusetts senator Elizabeth Warren is in constant motion. She often takes stages at a run, zigzagging around the edges of crowds, waving and giving high fives like Bruce Springsteen. Speaking to groups of supporters, she rocks on her feet, or rises to her tiptoes, with feeling; occasionally she tucks her mic under her arm to clap for herself or cuts the air in front of her with her flat palm. She’ll beat her chest for emphasis, speak so passionately that she gets winded, and throw a fist in the air as a symbol of defiance and determination. One afternoon in Nevada, perched on a punishingly high stool in front of several hundred people at a brewery, she kicked her feet out in front of her with such force that I feared she’d tip over backward.

Watching Warren this steamy summer as she works to move her party through the perilous wilderness of the Donald Trump administration, through the midterms and her own reelection to the Senate, and then perhaps toward a run for the presidency, she appears to have committed her whole body to the effort. Like if she stops moving, the whole world will end.

In recent months, she has hopped not just between Washington, D.C., and her home state but also to Reno and Las Vegas to campaign alongside a slate of Nevadan candidates; to Denver and Salt Lake City to fund-raise; to the Texas border to visit family-detention centers; to Iraq with Senator Lindsey Graham. Within an hour of Trump’s announcing his nomination of Brett Kavanaugh to replace retiring justice Anthony Kennedy, she was striding purposefully toward the Supreme Court steps, where a knot of furious protesters gathered in the dark were bellowing, “Hell no, Kavanaugh! Hell no, Kavanaugh!”

“We are in the fight of our lives,” Warren repeated — twice — when she got to the microphone.

All of the movement, the travel, the nervous animal energy, is in service of this idea: We’re in a fight. She is in a fight.

In the absence of a clear favorite to challenge Trump and the Republicans, Warren has emerged in just the past few weeks as the de facto leader of the Democratic Party, and accordingly, the candidate-of-the-moment for 2020. It should have been obvious: She has the progressive vision and drive, the willingness to go tweet-to-tweet with the president, and that boundless stamina. Perhaps it was hard in the wake of 2016 to imagine pinning Democratic hopes on another woman. But sometimes you need a crisis (or five) to see the obvious, and this summer’s cascade of them has brought Warren’s role into sharper relief.

It’s a shame that perhaps the fakest and most clichéd pose a politician can try to strike is that of the outsider. It’s a shame because Warren isn’t just another silver-haired pol braying about bringing Main Street to K Street — she actually is an outsider, despite the considerable power she’s amassed during her nearly six years as a senator.

An Oklahoma native, commuter-college graduate, Harvard law professor, and bankruptcy expert, Warren came to national consciousness about a decade ago. Having written The Two-Income Trap: Why Middle-Class Parents Are (Still) Going Broke with her daughter, Amelia Warren Tyagi, she’d visit Jon Stewart’s Daily Show to unspool deft yarns that helped Americans see how profoundly they were getting screwed: by the banks, by credit-card companies, by wealthy corporations, and by the government enabling all those entities. As a civilian, Warren chaired the 2008 Congressional Oversight Panel on TARP, during which she memorably disemboweled Obama Treasury secretary Tim Geithner and proposed a consumer-protection agency that Barack Obama made a reality. But Obama passed on her to run the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau precisely because she was too outsider-y, too challenging a figure for some Democrats, let alone Republicans.

Then, in 2011, Warren, who’d never run for office, decided to pursue the Massachusetts Senate seat that, after Ted Kennedy died, went in a special election to frat-boy Republican Scott Brown, who boasted high favorability ratings and a pickup truck. Warren ran an unwieldy campaign, in which she was tagged by the press as an awkward, hard-to-love candidate, and took the seat by only seven points — the spread that year in Massachusetts between Obama and Mitt Romney was 23. Nonetheless, Warren’s defeat of a popular Republican incumbent offered evidence — back before Bernie Sanders’s 2016 showing, before the growth of the Democratic Socialists of America, before Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez — that, after years mired in Wall Street–boosted centrism, Democrats could prevail by embracing a populist strain of economic progressivism.

But being in power is different from railing against it. In 2014, Warren was elected to party leadership and assumed a role that had been created for her as strategic adviser to the Democratic Policy and Communications Committee. Many saw the move as coming with costs: binding her to colleagues with whom she might naturally be at odds, including now–Senate minority leader Chuck Schumer, whose ascension in the 1990s coincided with the finance-industry-aligned era of the party.

In 2016, Warren disappointed legions of her supporters by deciding not to challenge Hillary Clinton for the Democratic nomination. She provoked further ire in some quarters of the left by refusing to endorse the man who did run against Clinton, Vermont’s senator Bernie Sanders, sitting out the primaries until the race had been decided, at which point she threw her support to Clinton. In the days after Trump’s inauguration, Warren annoyed progressives once more when, as a member of the Banking Committee, she dutifully voted for Ben Carson as secretary of Housing and Urban Development. Accepting a president’s nominees except in the rarest circumstances had just been the way of things, until New York senator Kirsten Gillibrand contested nearly all of Trump’s Cabinet picks last winter. By the time of the full Senate vote on Carson, Warren had gotten the memo: She voted not to confirm him.

The ongoing parade of horribles offered up by the Trump administration has given Warren an opening to showcase anew her prickly pugilism, starting with the moment in February 2017 when Majority Leader Mitch McConnell ordered her off the Senate floor for refusing to stop reading a letter from Coretta Scott King objecting to Jeff Sessions’s nomination for attorney general. During a March Senate hearing, she tore into Carson on how housing policy has expanded the wealth gap between blacks and whites: “It is HUD’s job to help end housing discrimination. That’s what the law said. You said you would enforce these laws. You haven’t, and I think that’s the scandal that should get you fired.”

The battles have burned hottest with Trump himself; it’s clear that Warren scares the president nearly as much as that other 60-something white grandma did, and he devotes an inordinate amount of energy to insulting her. He’s built one of his reliably racist shticks around his nickname for her, “Pocahontas” — deploying it at least 26 times between 2014 and 2017 — in reference to her claim as a young law professor from Oklahoma that she was part Cherokee. A former college debater, Warren has been assiduous in her commitment to bark back at him, riling him further with tweets about his “trash talk” and “incompetence,” calling him “creepy” and a “thin-skinned bully who thinks humiliating women at 3am qualifies him to be President.”

Warren’s willingness to sink her teeth into the president’s ankles has turned out to be a smart tactical move. It puts her in the news cycle right along with him, while most Democrats struggle to get a spot of media time in a landscape dominated by Trump. The day after his Helsinki performance, Warren is aghast. “It was a fictional moment, only it was reality,” she exclaims. “Never before have I seen a president attack America at the same time he’s doing a public display of affection for a dictator.”

Warren has in these past two years stoked and fed off grassroots rage, especially that of resistance women. She cheered on hundreds of female activists occupying her Senate Office Building in June to protest family separations, and during a fiery speech at an immigration rally in Boston, she called for “replacing ice with something that reflects our morality and that works.” That the Supreme Court nominee Kavanaugh is not simply a Federalist Society–approved conservative but a man who publicly labeled Warren’s Consumer Financial Protection Bureau a “threat to individual liberty” might be the closest Trump has come to hanging raw meat in front of a hungry bear. While Schumer speaks with toothless pragmatism about which strategy his caucus might choose to block Kavanaugh, Warren has hit the judge at every rally, on every cable-news show, and via every social-media platform she can lay her fists on, portraying him as someone who’ll overturn Roe v. Wade, take away health care, and protect Trump should he be indicted.

In the very near past, much of Warren’s agenda would have been considered untenably far left, but now it’s practically standard for serious Democratic contenders. She wants to reverse the new corporate tax benefits and invest in stemming the opioid crisis, bring college costs down, institute single-payer health care, alleviate consumer debt, strenuously regulate financial institutions. She talks about passing the Dream Act and enacting humane immigration reform, shrinking the race and gender wage gaps, remaking the criminal-justice system — “instead of jailing some kid who gets caught with a few ounces of pot, let’s put the banker who financed the drug deals in jail” — and passing a constitutional amendment to establish the unfettered right of eligible Americans to vote.

But first she has to train this puppy.

Warren and her husband, Bruce Mann, greet me at the door of their Cambridge house on a morning in early July. Mann, whom Warren met soon after the end of her first marriage, and whom she proposed to and wed in 1980, appears (at least to an outsider’s eye) to be one of those Good Husbands™, in the Marty Ginsburg mold. A Harvard law professor and historian of bankruptcy, Mann radiates both adoration and admiration for his wife. He stands still while she’s in motion; he smiles as she talks; he commutes to D.C. whenever his class schedule permits. Last summer, for their anniversary, he installed shelving in their D.C. home because he knows how much Warren likes organized closets and also that she has no time to hang shelves. This summer, he gave her a different kind of gift.

As we speak near the front door, a small crash echoes from the back of the house, as if perhaps a piece of furniture were being dragged across a stone floor.

“Is that — ” I ask.

“Yup,” Warren replies. “That’s the puppy.”

Ten days before, Warren had returned home from Washington to find a baby golden retriever waiting for her. Their last golden, Otis, died of cancer five days before her 2012 election. Warren says she didn’t tell people at the time for fear that saying it aloud would lead her to start crying and never stop. And then suddenly she was a senator, with an office in another state; the logistics of a dog seemed impossible. Recently, in these darkest of weeks, Warren says, she and Mann decided it was time to stop fretting over why it was impractical and just do it. She beams at her husband. “It’s all thanks to Bruce and his willingness to make it work. It’s the three of us in it together.”

And so we head to the side porch to meet Bailey, named after Jimmy Stewart’s George Bailey, the community building-and-loan officer from It’s a Wonderful Life, whose adversary is the cruel corporate banker Mr. Potter. In the movie, Bailey calls his foe a “warped, frustrated old man” and asks him, “Do you know how long it takes a workingman to save $5,000? Just remember … this rabble you’re talking about, they do most of the working and paying and living and dying in this community. Well, is it too much to have them work and pay and live and die in a couple of decent rooms and a bath?”

The dog’s name is an unsubtle hint at the part Warren wants to play: the person who stands up for the rabble and against the warped and frustrated old men whose refusal to loosen their grip on power has been made disturbingly apparent in these past few years.

Opposing corruption, Warren tells me, “is becoming a much more defining part of my work,” and in September, she plans to introduce a big legislative package to combat it. She’s not just talking about the Citizens United–style influence of billionaires in elections, though the Mercer family has already funded a super-pac devoted to attacking her. She’s obsessed with the revolving-door corruption of lobbyists, the influence-peddling that gunks up the legislative process. “But boy, does it pay off,” she says. “The rich get richer, and everybody else eats dirt.”

“I really didn’t think that would happen,” Warren tells me, as we settle down to talk, in reference to Donald Trump’s victory, coming as it did after a campaign that openly cultivated sexist and racist resentments. Warren says she’s been shocked into a new relationship with feminism and is “more worried than ever before” about the erosion of women’s rights. She’d long cared about reproductive justice, sexual assault, and equal pay — but gender just hadn’t been her thing. Back when I’d first interviewed her on this porch in the fall of 2011, as she was kicking off her Senate campaign, she’d even been a little dismissive of the discrimination she’d face in a state that had, as I wrote then, elected fewer women to the House or Senate than had been put to death for practicing witchcraft.

In his first race, Brown had beaten another woman, Martha Coakley, who’d been Massachusetts’s first female attorney general and had badly bobbled her campaign, losing to a guy no one thought had a chance. A lot of people in Democratic politics were wary about gambling the party’s future on another untested female candidate. The calls that gutted Warren the most, she tells me, were from her friends who said, “You can run, but you better understand: Massachusetts will not elect a woman to an office this big.”

At this point, Warren’s eldest granddaughter, 17-year-old Octavia, traipses by in jean shorts and bare feet, looking like summer. “Where’s the puppy?” she asks. “Granddad’s got him upstairs,” Warren replies, and Octavia zips off to find them.

Warren and I are ostensibly addressing the anxieties about her 2012 race, but we could just as easily be considering a more current set of anxieties. I ask her if some people told her specifically not to run in the wake of Coakley’s loss, and she nods her head yes. “It wasn’t only, ‘Don’t do this; look at Martha Coakley.’ It was, ‘Don’t do this; we’ve already been forced back enough, don’t push us back farther.’ ” What she took from this, she says, was the realization that “the losses [of women] are so personal that they make it harder for the woman after that and the woman after that.” We’re definitely not talking about Martha Coakley anymore.

Warren holds my gaze as she continues: “At the end of the day, you just can’t let that [stop you]. You could’ve said to me, ‘You’re going to get all your skin burnt off,’ and my answer would have been, ‘That’s going to be part of the prize.’ Every person who said to me, ‘Massachusetts won’t elect a woman,’ or, worse, ‘When you lose, it will set back the cause of women here in Massachusetts,’ made me lean harder into the decision to run.”

The question of whether Warren will run for president hangs around her not like a cloud but like a glittery bubble — she’s a special figure because she’s a leader, and she might be the leader. Traveling in Nevada alongside her Senate colleague from that state, Catherine Cortez Masto, Warren is the one who’s recognized in the airport, in the hotel. Everyone I speak to in the weeks I’m reporting this story excitedly asks the same question: “Is she going to run?,” before telling me whether they think she should.

The opinions reliably fall into three categories. There are those — often political reporters and longtime Democratic denizens — who remind me that she was a weak candidate in 2012, that her politics are too far left, and that she’d activate the Trump base; an early 2017 poll showed Trump losing to a generic Dem but winning against Warren. Some others, many of them older feminists, tell me regretfully that they love her but Clinton’s loss showed that America hates women too much, especially older ones. Warren would be over 70 when she ran, and there’s simply too much on the line to risk it.

It’s younger people, along with women recently awakened to activism and some experts who’ve been tracking the unprecedented wave of female candidates winning Democratic primaries, who aren’t just optimistic but enthusiastic about her potential. They say that she is a brawler and thus the candidate that this historical moment demands, that she’s the perfect person — left, female, and furious — to avenge the loss of Hillary while also bringing to the White House a politics far more progressive than Clinton ever would have.

“What I find especially interesting,” says Kelly Dittmar of the Center for American Women and Politics at Rutgers University, “is that critics will push back against any claims that gender was the cause, or even part of the cause, for Clinton’s defeat, but will then question whether Democrats should nominate a woman again in 2020.” Of course, she says, gender — not just women’s but men’s — will be part of the puzzle of future presidential politics; it always has been. “But it would be naïve to assume that a candidate’s gender will alone be the ticket to success or the death knell.”

Though early polling is a fool’s errand, Warren is regularly named, along with Sanders and Joe Biden, as one of the top three candidates for 2020, with other presumed possibilities — Gillibrand, California senator Kamala Harris, New Jersey senator Cory Booker, Los Angeles mayor Eric Garcetti — trailing behind them. One June Harvard-Harris poll put Warren fourth, behind Biden and Sanders and Clinton (who Will. Not. Be. Running. Again). But a May Suffolk University poll of New Hampshire Democrats had Warren well ahead of the others, with 26 percent over Biden’s 20 and Sanders’s 13.

Warren is up for reelection in Massachusetts in November. She can’t say that she is running for president. So officially, it is accurate to say that she is not.

But of course she’s running. Even if she doesn’t really want to be president, she should run — as should several of her female colleagues — to help normalize women’s campaigning for president and finally correct the conversation about whether a woman can win and make it instead about which woman will win. She should run to give voters a choice, to push the field to the left, and to leverage her history of lambasting corrupt capitalist excess to properly shame the Trump kakistocracy. And, for what it’s worth, I think she does really want to be president.

“I’m going up that hill,” Warren tells Nevada Democrats in June, supposedly describing her ongoing struggle against Trump and the right. “I need you with me. We must change the face of power.”

Assuming Warren declares, she’ll have to reckon with the fact that she’ll be depicted as the reanimation of Hillary Clinton, no matter the stark differences between the two. Warren is perhaps the national political figure who first harnessed the energies of post–Occupy Wall Street American progressivism and served as a rebuke to the center-left politics that defined Clinton. But in declining to run in 2016, she ceded some of that symbolic claim to Sanders. In retrospect, it was likely a mistake for her to have sat it out, as it had been for Clinton to decline to challenge George W. Bush in 2004. Women talking themselves out of running has always been a problem, one that too often winds up biting them in the ass later, when they do step up.

Many of Sanders’s staunchest fans still hold it against Warren that she didn’t endorse him. At a speech at the ACLU convention in Washington in June, Warren laid out a progressive vision to a wildly enthusiastic crowd, but one woman at my table looked dubious. “She all but announced her candidacy,” Coretta McKinney, a 46-year-old real-estate broker in Virginia, told me, probably referring to Warren’s line about the need to put “more women in positions of power, from committee rooms to boardrooms, to that really nice oval-shaped room at 1600 Pennsylvania Avenue.” McKinney said that she was impressed by the content of Warren’s speech but that she’d never vote for her in a Democratic primary. Warren hadn’t “atoned” for campaigning with Clinton, McKinney went on, citing Cenk Uygur’s leftist media network the Young Turks as her go-to source for political analysis.

“I endorsed Hillary after she was the Democrats’ nominee and Bernie had withdrawn,” Warren protests when I tell her this story (it is not quite true that Bernie had withdrawn, but it had become impossible for him to win). But then she tries to put a good face on how harshly she’s judged by some Sanders diehards (see the “#JudasWarrenSellout” spray-painted beside a highway in Northampton, in 2016): “There’s a part of me that smiles when I hear this. We’re Democrats. We don’t fight to get our taxes cut or for some loophole in government regulations. We fight from the heart for what we believe in — I wouldn’t change this if I could.” Then she repeats something I’ve heard her say before, which is that the 2016 election is in the rearview mirror and “all we can do now is try to bring this family together and move it forward.”

Which is not to say that moving forward will be easy. Warren’s style — her competence, precision, and practicality — combined with the apparently endless thrill of hating Hillary Clinton, along with (dubious) stories pushed by the right to maximally alienate the left about her purportedly cozy private relationships with the bankers she publicly assails, plus the fact that she is the same age, race, and gender as the former Democratic candidate, mean that Elizabeth Warren basically is Hillary Clinton — or could be cast as smudgily indistinguishable from her within about five minutes of entering a presidential contest.

It’s ridiculous. Warren is the woman who famously called out Clinton for caving on bankruptcy reform. Yes, like Clinton, she’s ascended to elite status within her party, but, she says, it gives her a chance “to push harder on the issues I care about. I’m an outsider who now has a lot more leverage.” Soon after accepting her post, Warren persuaded her fellow party leaders that it was time for a vote to commit to grow Social Security, getting out of the defensive crouch of merely arguing about how much or how little to cut from the bedrock program.

“Democrats never again as a group in the Senate have had the conversation that starts with ‘Let’s figure out how much to cut from Social Security,’ ” Warren says. “I remind people: ‘If you were here, you signed up to expand Social Security.” Sometimes, she says, they quaver: “ ‘Did we do that?’ ” Warren grins and nods vigorously. “Oh, yes we did!” It matters, Warren says, because when Democrats return to the majority, they’ll be prepared with a “policy piece that we all agreed to.”

As more proof of how she’s successfully pushed progressive approaches, she cites the now broad acceptance of a bill that would set student-loan interest at the same (lower) rate offered to banks by the Federal Reserve. In 2015, she used her clout to publicly rap Obama-appointed Securities and Exchange Commission chair Mary Jo White for slow-rolling the enforcement of the Dodd-Frank rule requiring corporations to release CEO-worker pay ratios. As a result, we now know, for example, that the CEO of the conglomerate Honeywell makes $16.8 million a year, when the median worker makes $50,296 — a 333-to-1 ratio. And just this spring, thanks to pressure Warren applied to her caucus, the progressive stalwart Rohit Chopra was tapped to serve on the Federal Trade Commission.

Notwithstanding all this, Warren has already been described, in her 2012 race, as “hectoring” and “schoolmarmish”; in 2016, Mika Brzezinski, that great advocate for women’s “value,” suggested that Warren was “shrill … unmeasured and almost unhinged.” In a 2016 story about the senator, the New York Times characterized Warren as “imperious” and “never short on confidence” as she swept through congressional hallways in her “jewel-toned jacket” — a frame absolutely chilling in its familiarity. Last week, after Warren called herself at a New England Council breakfast a “capitalist to [her] bones,” a handful of left-wing media figures slammed her for what they saw was selling out to the donor class in advance of a presidential run. No matter that Warren has, throughout her career, described herself as a capitalist and a fan of regulated markets, at the same time as she has gone after banks and corporations for maximizing profits on the backs of the working and middle classes — those are just details. It can all happen again.

And yet. It may also be different this time. Maybe not enough to land us with a lady president, or maybe exactly that different. After all, in part in reaction to Clinton’s loss, and to Trump’s victory, millions of America’s women — and at least some of its men — have been energized and have educated themselves about a slew of progressive issues. Many of them crave leftist leadership, at least when it’s presented as a call for affordable college and health care, higher wages, and humane immigration and gun policies. At least some are in it for something blunter: female leadership. They see in this era of Women’s Marches and a female-led resistance, with Roe at stake and the #MeToo movement having exposed the rot at the core of patriarchal power structures, a chance to replace disappointing and abusive men with competent women.

During her first Senate race, when Warren met little girls on the campaign trail, she began a practice of kneeling down to say: “My name is Elizabeth and I’m running for the United States Senate because that’s what girls do.” She figured, she tells me, “that if nothing else comes of this race other than that, there will have been some good.” It became a thing, with fathers bringing baby daughters to her, mothers and grandmothers asking for pinkie swears and multigenerational photos. “It’s one of the pieces for me that makes me so glad to have run for office,” Warren says. “And so glad to have won.”

Warren speaks with assertive pride about what a tough law professor she was. “My classes were routinely regarded as the hardest in the law school,” she says, explaining that it was important for both her male and female students to see that being demanding and “excellent” was “a part of who women are.” She knows this sounds obvious, but the obvious can evaporate when “time after time, a young woman goes into a room and there’s nobody there but men.”

Warren’s willingness to present herself as a hard-ass teacher is something to behold. After the indictment of 12 Russian nationals for hacking the DNC server in an attempt to interfere with the 2016 election, Warren tweeted to Trump that he should “cancel your ridiculous Putin summit and get your butt on a plane back to the United States.” In a pep talk with her state campaign staff in June, Warren baldly declared, “This is an administration that is rife with corruption, with favoritism, and with just outright stupidity.”

Women who openly admonish men as if they’re children, who are frank about men’s intellectual shortcomings, don’t tend to be beloved; in this climate, they’re vulnerable to charges of elitism and worse. Feminists have long noted how some men rear back from women who remind them of the mothers and teachers who had authority over them in their youth, and so I blanch a bit when I hear Warren, on the road, saying how as a second-grader she used to line up her dolls and reprimand them for not handing in their homework on time, or crowing to a Girl Scout leader about how she herself had been not only a troop leader but a “cookie chair.” Not once, she says, with a dramatic pause.

“Twice.”

But the woman who insisted on modeling female excellence and toughness as a law professor isn’t backing away from that now. In Reno in June, she told the familiar tale of her childhood spent at “the ragged edges of the middle class,” but this time lingered not on her janitor dad and three older military brothers, but rather on her mother, whom she heard one day after her father’s heart attack weeping and vowing, “We will not lose this house, we will not lose this house.” As Warren told the crowd, her mama then “blew her nose and walked to the Sears” to get a job, and indeed wound up saving the house.

This narrative is key to Warren’s brand: to the spirit of persistence, a meme gifted her by McConnell when she tried to read Coretta Scott King’s letter. McConnell told her to stop; she kept going; he threw her off the floor. Then he explained that he’d had to silence her because she’d been warned, she’d been given an explanation, but nevertheless she persisted.

Warren loves it. She embraces the memes, relishes being a piece of resistance merch, plays to the crowd, hollering, “Nevertheless …” and waiting for the “She persisted!” In part, this may be because she understands sound-bitten American politics in a way that she didn’t when she had trouble on the stump in 2012: It’s about the line, the sell, the MAGA hats, and the $27 average donations. This is what smart and capable female candidates actually need to learn, if they’re not to get written off as stilted and boring — how to draw a crowd, get them to their feet, lead a rowdy call-and-response. Ideally, your signature line pithily captures what you stand for, and in Warren’s case, persistence neatly embodies many of the dynamics of 2018: a vile white guy silencing the white woman contesting the nomination of another vile white guy by reading the letter of a black woman who’d warned of these monsters years earlier. The line also points to the larger hope: that American women on the right side of history may yet prevail. McConnell’s words offered a blueprint for a kind of mass women’s rebellion. Elizabeth Warren gets that.

At the Nevada convention, two women — one a former Hillary supporter, one a former Bernie supporter — wearing jackets with the message WE REALLY CARE! DO U? affixed in white tape are there for Warren, as well as Cortez Masto and Representative Jacky Rosen, who, after winning her first-ever race in 2016, has a chance to unseat Republican senator Dean Heller in 2018. “Yeah, we’re activists,” Denise Quon says to me when I ask about her motivation for being there. “But mostly we’re just pissed off!”

It’s Warren’s willingness to be pissed off alongside them that attracts many women to her. When in the fall she told her own #MeToo story on Meet the Press, about back when she was a “baby law professor” and a senior faculty member chased her around his desk trying to grab her, she recalled thinking, “If he gets hold of me, I’m going to punch him right in the face.” And Warren is so proud of her Twitter takedowns of our president that she actually published many of them, in Twitter format, in her recent book, This Fight Is Our Fight.

Warren is on a short flight between Reno and Vegas that turns out to be pretty turbulent. It already feels like passengers are jumpy as we descend into McCarran airport when a kid yells, “Hey, there’s Air Force One!” The man by the window in my row opens the shade, looks out, and matter-of-factly affirms, “Trump’s here.”

The plane is buzzing with the sudden awareness that the president is in town and that onboard with us is his nemesis. As soon as we stop taxiing, a young woman sitting behind Warren asks the senator to make a video message for her roommate. She immediately complies: “Stay in the fight, Allison!” Warren exhorts over the back of her headrest, straight into an iPhone.

As Warren deplanes, a diminutive middle-aged stewardess embraces her, pulling her down to plant a big kiss on her cheek. Stepping into the airport, with phones and news alerts revved back up post-flight, we’re all reading the same headlines: Trump has gone on a tirade about the senator in advance of her visit to the city, calling her Pocahontas. He’s joked about how he’s been pressured to apologize to her for his racism, and the crowd has chanted back at him: “Don’t!” (In the line to board the plane in Reno, an older man behind her remarked to his wife with a smirk, “Maybe I’ll get to sit next to Pocahontas.”)

In the cab to my hotel, the driver is playing conservative radio, and I learn about the building frenzy over Sarah Huckabee Sanders’s ejection from the Red Hen restaurant. San Francisco right-winger Michael Savage reads a passage from his upcoming book on “liberal hysteria,” predicting that we’re heading into a civil war.

Two hours later, Warren — who has made a pit stop to pay her regards to the ailing Harry Reid — is in the brewery in Henderson in front of several hundred supporters, four out of five of them women, many in persist T-shirts, one waving a persist bumper sticker.

“This is a dark time,” Warren begins, meditating on Trump’s having recently referred to human beings as “animals.” Her painted blue toenails peek out of black pumps, a navy-blue cardigan is shedding thread in the back. She mentions the Pocahontas speech from earlier that afternoon. “He thinks he’s gonna shut me up?” she says. “That’s not gonna happen, baby, no, no, no.”

A woman stands and asks Warren, “Does the Democratic Party have a plan for the next time they repeal Obamacare?” Warren’s answer begins with Trump’s inauguration. She sat close to him as he was sworn in, she says, “burning [the moment] on the back of my eyeballs,” which turned out be useful for those times when she gets worn out or demoralized and wants to rest. As soon as she closes her eyes, she jokes, “I see Donald Trump being sworn in, and I’m back!”

Continuing to recount the inaugural day, she recalls how she felt close to despair returning to Boston in the evening: Republicans now held the White House, the Senate, the House, and the state legislatures; Obamacare and Planned Parenthood funding would likely be rolled back by Monday, Tuesday, Friday of the coming week. The next morning, things didn’t seem much better, but she got out of bed, threw on some clothes, and started toward the Boston Common. That’s when the army came into view. “Women,” she says reverentially. “And friends of women — that’s what we’re now calling you guys. It was the biggest protest rally in the history of the world. And it wasn’t organized by some fancy group of professional organizers in Washington, D.C. It was women who’d come off the sidelines.”

Another attendee inquires about top-down party strategy with regard to the proposed merger of the Labor and Education departments — can Democrats stop it? Warren pauses and gets quiet. “I think we can,” she says, “for another four and a half months.” That’s it. Then it’s up to the people, at the polls.

Her answer to both these questions is the same: There is no magic formula from on high, from her position in the upper echelons of political leadership. Now there is only the power of the masses, which is why Warren vibrates with intensity as she tries to express to these eager people that they, not she, are the answer to what will happen next, the only real tool the left has left.

After we talk on her sun porch, Warren has to rush to that big outdoor town hall in Natick. But before she goes, she has an alteration to make. She’s ordered a bunch of gauzy open-front cardigans to put over her uniform of black pants and a black tank top. They cost about $13 each, she says, but they’re too long, hit her too far down the thigh, so she’s planning to cut the bottom off the aqua one she’s about to wear.

I point out that if she just chops it with scissors, the knit will come unraveled. She shoots me a slightly withering look: “Well of course it will unravel, but it will just roll up at the bottom.” Fair enough, and as I stand watching this operation, I mention that I’ve just come from a weekend in Maine, where I’d turned away from the news for a couple of days and briefly felt the relief of disengagement. Warren cuts the sweater methodically, using the first scrap to measure how much to take off all around.

“You know what I love to do?” she offers. “I love to go to Target with Amelia and just spend the day there.” Her daughter, Amelia, is the mother of Octavia and Warren’s two younger grandchildren; she lives in L.A. “We just wander around in there, look at the patio furniture, the pajama section. It’s like six hours of tuning out.” You spend six hours at Target? asks a staffer who’s there to accompany us to Natick. Warren looks up, surprised. “Well, not just at Target. We go to BJ’s; we each have things we like to eat there. Then I get the socks I like at Macy’s.” Warren’s voice gets softer. She’s talking mostly to the sweater now. “It’s just a few hours, six hours that I don’t have to think about Mitch McConnell. That’s all I need.”

Here is a 69-year-old woman, scissoring the bottom off a cheap sweater at her kitchen island as a lunatic white patriarch of a president rages against her, using his tiny thumbs and a social-media platform. On some level, it feels absurd — the contrast between the enormously consequential political fights and the people waging them, each small in his or her own way. There’s a muffled crash from upstairs, where Bailey is playing, perhaps with Granddad and Octavia.

What happens next? Who can get us out of this? This is the current condition, the endless stream of questions we ask ourselves on our trips to Macy’s, as the pets we count on to repair our hearts chew on our furniture. On cable news, pundits and politicians pontificate and predict with performed authority — and we create the market for their assuredness because it’s so hard not to know. Nobody wants to have to fight all the time, to shake and shimmy with the effort of it, so we seek a leader who’ll vow to take us forward, reassure us so we don’t have to worry and work and argue and stay up all night scared.

The problem is that it was the assured predictions, the 85 percent chance of victory, the promises of inevitability, that landed us in this fucking mess to begin with. It will be tempting to have a million conversations over the next few years in which we stroke our chins and ask wise questions about Elizabeth Warren’s chances. Those who are used to being called upon as consultants and political gurus will wonder, like Beltway Carrie Bradshaws, whether America is ready for a female president. Experts will run the numbers, talk to focus groups, tally up the probabilities, and churn through the losses we’ve already sustained. They’ll tell us to stay safe and center, or to bank left because that’s the trend, or that Warren isn’t left enough to be on trend. They’ll argue about whether the way to win is to attack Trump or talk health care. Some will contend that turning to another woman — another older white blonde who can be portrayed as imperious and shrill — will mean doom; others will insist she’s our only hope.

But the fact is that none of us — not one of the people who’s going to try to answer this question with authority — actually knows what’s possible, what’s impossible, what’s going to happen next. Because everything is different now. We are different too.

That afternoon, Warren will stand in front of 1,500 people in a sun-blasted field. The people in the crowd have interrupted their own holiday weekends, their getaways from the news, to come listen to this woman in her chopped-up aqua sweater answer questions and sweat and clap for them and for herself. The first man who stands to ask a question will tell Warren that she met his daughter back when she ran for the Senate in 2012, and that she pinkie-swore to that little girl that she could become a senator one day too.

Warren will remind this crowd that their very presence, that such a mob would show up on this holiday weekend, is a sign of the uncharted political territory we’re in.

“We are a changed people,” she says. “And that means we are a changed democracy.” We must change, we must imagine that it’s possible.

“We’ve got to throw it to democracy” is what Warren said to me over our first lunch in May. This is her solution, not some tricked-out plan devised by a highly paid Democratic consultant, while the volunteers and protesters pound the pavement all day. Warren is looking past the consultants and party leaders to the women — and the men — who are out there like her moving, fidgeting, throwing punches in the air.

“I’m optimistic,” she said to me over that lunch. “But I’m furious.”

*This article appears in the July 23, 2018, issue of New York Magazine. Subscribe Now!