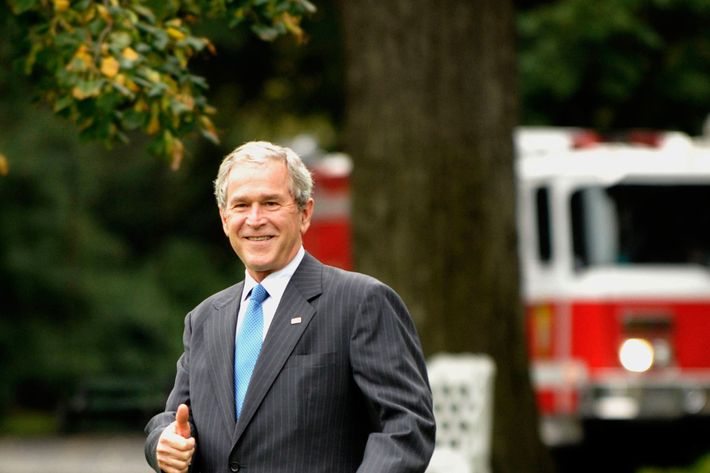

It is comical — in the second-time-as-farce way, not the ha-ha way — that the anniversary of 9/11 has coincided with a sudden revival of neoconservative thought. The neocons never really went away or even questioned their analysis. (The conflation of uncertainty with weakness is itself a defining tenet of neoconservatism.) The terrifying emergence of ISIS and genuine questions about the Obama administration’s lurching response has created a space for the Republican Party, after flirting with noninterventionism, to re-embrace its Bush-era ultrahawkery.

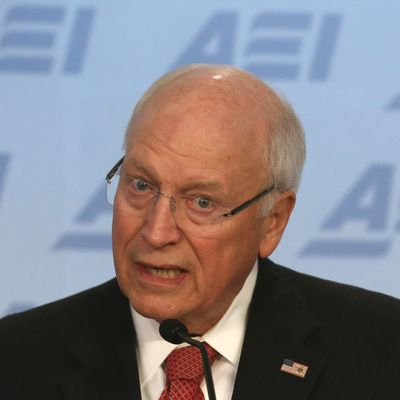

Signs of the neocon revival include the party shedding whatever lingering inhibitions it had about associating itself openly with Dick Cheney, who delivered a deliriously militant speech at the American Enterprise Institute, addressed the House Republican conference (and received a “rapturous reception”), and was celebrated in a Wall Street Journal editorial (headline: “Dick Cheney Is Still Right”). They also include the spreading use of conservative responses to ISIS that eerily echo its impulsive response to the attacks of 13 years ago.

During the Bush years, “neocon” evolved into a catchall term of abuse, so it is important to think precisely about what it means. Not all supporters of intervention are neocons. (Jeffrey Goldberg makes a sensible, if not ironclad, case for the Obama administration’s plan.) Not even all right-wing supporters of intervention are neocons (Byron York, who seems to favor intervention, nonetheless warns frankly and honestly about ways it could go wrong.) Rather, neoconservatism is an especially virulent strain of hawkishness that fetishizes simplistic absolutism. The neoconservative response to ISIS displays several distinct qualities:

1. The use of the term “serious” as a bludgeon. “The American Enterprise Institute is one of those places where serious matters receive serious attention, and that’s the spirit that brings me here this morning,” announced Cheney. Ted Cruz, who has positioned himself as the most vocal spokesman for neoconservatism among the party’s presidential field, calls Obama’s approach “fundamentally unserious.” Jennifer Rubin, the neoconservative pundit, assails “Obama’s consistent unseriousness about the Islamic state.” Charles Krauthammer asserts, “The question is his seriousness.”

The constant repetition of this word is not coincidental. Its purpose is to present absolutism as a substitute for thought.

2. An apocalyptic assessment of the threat. The prospect of ISIS establishing a permanent state, or dominating a failed state, would have dire strategic and humanitarian consequences. But the threat is long-term — “American intelligence agencies,” the New York Times reports today, “have concluded that it poses no immediate threat to the United States.”

Neoconservatives can’t accept threat modulation. “ISIS is a grave, strategic threat to the United States,” warns Cheney, “The situation is dire and defeating these terrorists will require immediate, sustained, simultaneous action across multiple fronts.” Rubin expresses her alarm that “the president doesn’t believe the Islamic State is a current threat to the U.S.” And Cruz rages:

[Obama] then sought to diminish the threat of ISIS to suggest that they’re primarily a regional threat and what we didn’t see tonight was a commander-in-chief focused on U.S. national security interests who stood up and said there are radical Islamic terrorist who have declared war on the United States who are murdering Christians, who have murdered two American journalists and who have promised to take jihad to America, and we will respond with overwhelming air force to take them out.

3. Blurring distinctions between different Muslims. The most forbidding challenge posed by ISIS is that it is wreaking havoc not only against American allies (like Kurdistan) but also against American foes, like Syria and Iran. One possible response, as the United States is already doing by partnering with Iranian-backed militias, is to identify ISIS as the greater evil and accept alliances of convenience. Another is to refuse to intervene out of the belief that opposing Iran and Syria takes priority. (David Frum makes this case.)

Neoconservatives reject both these alternatives in favor of a heroic struggle against evil in all its forms. In his speech, Cheney threatens strikes against Bashar Al-Assad and the Iranian regime (“we will take military action if necessary to stop” from acquiring nuclear weapons) even while prosecuting an existential war against their enemies.

Cruz, speaking at a conference of Middle Eastern Christians, provoked boos by proclaiming:

“ISIS, al-Qaida, Hezbollah, Hamas, state sponsors like Syria and Iran, are all engaged in a vicious genocidal campaign to destroy religious minorities in the Middle East. Sometimes we are told not to loop these groups together, that we have to understand their so called nuances and differences. But we shouldn’t try to parse different manifestations of evil that are on a murderous rampage through the region.”

Especially instructive here is Cruz’s invoking “so-called nuances and differences” between groups that are at war with each other.

4. Waving away any possible complications associated with excessive involvement. The nub of neoconservatism is a belief that the only possible strategic failure is the insufficient use of military force. This is more of an atavistic reflex than a cogent form of thought. Cruz assails Obama, “Instead he suggested targeted attacks and focuses frankly on political issues that are peripheral from the central question of how we protect America from those who would take jihad to our nation.” Targeted is bad. Political is bad. Protecting is good.

Here is Rubin’s response:

[Obama] insisted, “This strategy of taking out terrorists who threaten us, while supporting partners on the front lines, is one that we have successfully pursued in Yemen and Somalia for years.” But if the Islamic State, which occupies vast territory and is highly trained and very well organized, than I suppose it won’t work.

That is not even an English sentence. Nonetheless, the underlying impulse is clear enough.

***

All these elements have in common a historic track record. In the wake of 9/11, neoconservatives both exploited and were victimized by a collective freak-out. All the things they are doing now, they did then: the “serious” trope, the hysterical threat assessment, the simplistic conflation of mutually antagonistic strains of Islam, and the complete lack of concern for the possibility of overreach. The memory of the 9/11 attacks has left most of us with some sense of sobriety and regret. The neoconservatives, by contrast, look back on that time of fear and rage with increasingly undisguised longing.