A couple of weeks ago, Tom Frank, author of What’s the Matter With Kansas?, sympathetically interviewed academic-activist Cornel West, both of whom agreed that Barack Obama has betrayed the left. I pointed out that Frank and West alike held in common a lack of familiarity with even the basic concepts of political science, which can explain how structural limits (like divided government and polarization) constrain the domestic powers of a president in a way that cannot be broken with ideological willpower or inspirational speechmaking. Now Frank has written a column (“All these effing geniuses: Ezra Klein, expert-driven journalism, and the phony Washington consensus”) assailing the influence of political science, which he views as a kind of corrupting force draining the left of its populist fervor.

The subject of Frank’s irritation is a triumphal, and probably a bit overstated, column by the aforementioned Klein, arguing that political science has conquered Washington. The argument drives Frank to distraction. He argues that political science has always run Washington and that political science is the main problem with Washington. Frank is tellingly wrong on all these things, but in one way he is dead-on: He has correctly identified the field of political science as the true enemy of his worldview.

A good chunk of Frank’s polemic is taken up with generalized experts of all kinds, not just those in the political science field. He distrusts them all as corrupt handmaidens of power. (Frank: “The powerful in Powertown love to take refuge in bewildering professional jargon.”) After establishing his anti-academic-populist bona fides, Frank provides his readers with an example of the kind of political-science-driven analysis that so perturbs him: a column by New York Times election analyst Nate Cohn that explains why the House map is prohibitively tilted toward the Republican Party, making the race for control of the chamber essentially out of reach this fall.

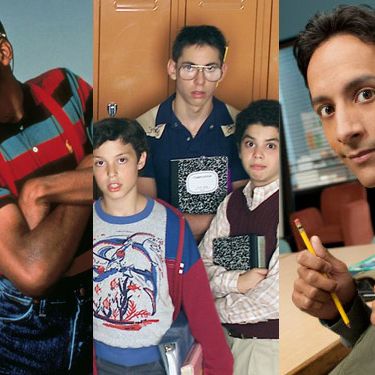

“It is this kind of strikingly unoriginal thinking,” responds Frank, “which I am sure is shared by the blue team’s high command, that explains why the Democratic Party looks to be headed for another disaster this fall.” Of course, if you believe Cohn, it is not the Democratic Party’s awareness of the GOP’s prohibitive structural advantage but the prohibitive structural advantage itself that explains why the Republicans are going to win the midterm elections. But to Frank, structural analysis is for the same kind of horned-rim-glasses-wearing geeks who are to blame for Vietnam and the financial crisis (two of the calamities he attributes to excessive reliance on academia).

True populists tell stories rather than use data. Though sometimes they still feel compelled to call their stories “data.” Here is Frank attempting to slam nerds like Nate Cohn to the ground with the power of facts, or factlike recollections:

Allow me to drop a single, disturbing data point on this march of science. You might recall that Democrats controlled the House of Representatives from the early 1930s until 1994 with only two brief Republican interludes. What ended all that was not an ill-advised swerve to the left, but the opposite: A long succession of moves toward what is called the “center,” culminating in the administration of New Democrat Bill Clinton…

So Frank’s “data point” is that Democrats lost the House in 1994 because Bill Clinton was too conservative. That assumption is belied by a mountain of evidence. Midterm elections structurally favor the out party. Additionally, Democrats had held for years or decades onto districts that had grown increasingly conservative at the national level.

Political science may not tell us everything about politics, but it certainly explains the broad contours: Clinton’s party was bound for a major course correction. Indeed, the political science actually undermines the response to the 1994 midterms that prevailed in Washington, which was that America had rejected Bill Clinton’s liberalism, or possibly even the New Deal itself. But, contrary to Frank’s fears, this sort of bloodless academic analysis carried hardly any weight among the political elite, who preferred to understand events by telling stories, albeit ones with the opposite moral than Frank’s preferred version.

At the end of his rant, Frank almost seems to concede that his problem with political science is that it leads to conclusions he finds inconvenient. “The fatalism here may be science-driven,” he concedes, “but still it boggles the mind.” Let that phrase roll around in your head for a moment. Frank has just told you everything you need to know here.