The Democrats’ 2020 primary fight has featured many pitched battles over policy questions. But every debate over Medicare for All, the Green New Deal, tuition-free college, or any other intraparty wedge issue has been colored by a meta-argument over the meaning of “political pragmatism.”

There are a wide variety of nuanced positions in the latter dispute. But one prominent line of argument among putative moderates is that Democrats mustn’t stray too far left ideologically, lest they alienate the great unwoke masses of middle America. After all, both chambers of Congress systematically overrepresent conservative areas (the Senate gives every state equal representation, and the average state is roughly 6 percent more Republican than the nation as a whole). Progress is possible, but only if Democrats pursue it on tip-toe and in baby steps.

A prominent leftist counter to this is that public opinion is both more progressive — and more malleable — than the centrists like to pretend. Ambitious, easy-to-understand policies like Medicare for All are actually more broadly popular than Obamacare-esque technocratic tinkering. In this view, the true constraint on radical reform isn’t the inveterate conservatism of the American hinterland, but the outsize influence of concentrated capital; “moderates” just use deference to public opinion as a false alibi for craven capitulation to their corporate paymasters.

As a bought-and-paid-for mouthpiece of the bleeding-heart bourgeois press, I’m professionally obligated to inform you that the truth is somewhere in the middle.

America’s electoral institutions really are biased against the left. Both polling data and historical experience suggest public opinion is a genuine obstacle to the realization of many progressive goals. Medicare for All polls better than the Republican approach to health care — and, under certain framing, enjoys majority support. But when surveys spotlight the policy’s implications for the tax code and the availability of private insurance, that support tends to decline precipitously. And the experience of single-payer campaigns in Colorado and Vermont lend some credence to those poll results. There is some reason to believe that most Americans would support single-payer if the totality of the policy’s consequences were made absolutely clear to them (i.e., that they would likely see an overall decline in their cost of living and enjoy stable access to their preferred providers). But there’s also reason to question whether reformers could succeed in giving voters such clarity, especially given how well-resourced their opposition’s messaging campaign is certain to be. Separately, many of the Democratic left’s ideas for redressing injustices that primarily afflict a minority of the population appear to be unambiguously unpopular — abolishing ICE, enfranchising current prisoners, and paying reparations for slavery (and/or other forms of anti-black discrimination and expropriation) all poll terribly. None of this necessarily means that Democrats shouldn’t support single-payer or other controversial policies. Obamacare had a negative approval rating when it was passed, and likely cost many congressional Democrats their jobs. But it also appears to have saved more than 19,000 lives. The point is simply that, on many issues, the left’s adversaries aren’t merely special interests but also mass opinion.

On other issues, however, progressives are right to think that the people aren’t their problem. Most voters aren’t rigorously ideological. The median American does not judge a policy by how it comports with her abstract theory of the role of government, but rather, by how well it lines up with her personal intuitions about fairness and which social groups the policy seems to benefit. For this reason, many ostensibly “left wing” or even “radical” policy ideas are actually popular with voters in both parties. On occasion, a red-state electorate will spotlight this fact by voting to expand Medicaid, strengthen unions, or raise the minimum wage. More often, though, the breadth of latent support for ambitious progressive reforms is obscured by the outsize influence that well-heeled interest groups and partisan elites have in determining which ideas are taken seriously enough to poll or debate.

Happily, Data for Progress (DFP) is working to change that. In recent years, the progressive think tank has conducted large-sample, neutrally worded national polls of various left-wing policies, including many that had yet to register in mainstream discourse. DFP then applies state-of-the-art demographic modeling techniques to estimate the likely level of support for said policies in every state and district in the country. This week, in a collaboration with Democratic data firm Civis Analytics, DFP released new poll numbers on 15 different progressive policies — including seven that are both very “left wing” by the standards of Beltway discourse and popular in all, or nearly all, 50 U.S. states.

Here’s a quick rundown of the seven things all Democrats should be comfortable saying on television:

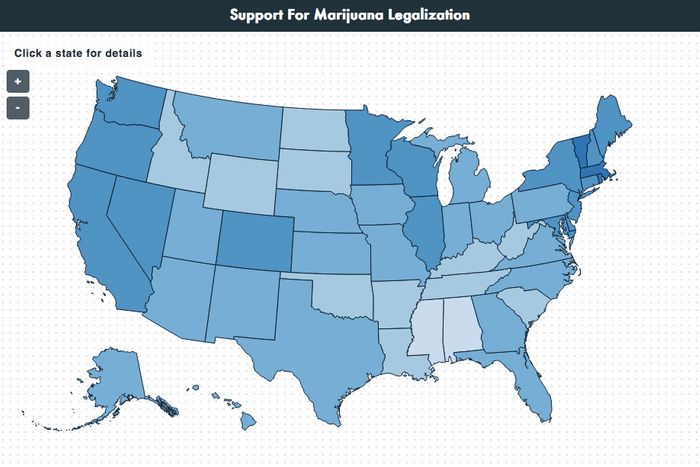

1) Weed should be legal.

Although legalizing marijuana is (something close to) a consensus position among 2020 Democratic candidates, Democratic legislators in many blue states are still dragging their feet. And on this front, ideology (and/or interest-group organizing) — not public opinion — is the obstacle to change. DFP’s poll is far from the first to find that ending weed prohibition is popular. But its survey nevertheless suggests that mainstream discourse hasn’t absorbed just how high the American public is on legal ganja: According to the think tank’s findings, legalizing marijuana isn’t just a majoritarian position in all 50 states, it’s a majoritarian position with Trump voters in 49. Which is to say: In every U.S. state but Mississippi, a majority of voters who support Donald Trump also support bringing weed off the black market (and even in the Magnolia State, 48 percent of Trump voters are 420-friendly).

What makes these findings especially impressive is that the wording of the DFP/Civis survey explicitly frames marijuana legalization as a Democratic policy, and provides Republican counterarguments to it:

Some Democrats in Congress are proposing a policy where marijuana possession would be legal for those at least 21 years old. Additionally the sale of marijuana would be legalized, taxed, and regulated. Funds from the marijuana taxes would go towards education and healthcare. Democrats say this would save taxpayers money in marijuana enforcement, keep people out of jail for simply possessing marijuana, and provide much needed tax dollars for education and healthcare. Republicans say marijuana is dangerous and its legalization will foster a culture of dependency and addiction. Additionally, Republicans suggest this would prove a public safety hazard leading to thousands of deaths as more people would use marijuana while driving. Do you support or oppose this policy?

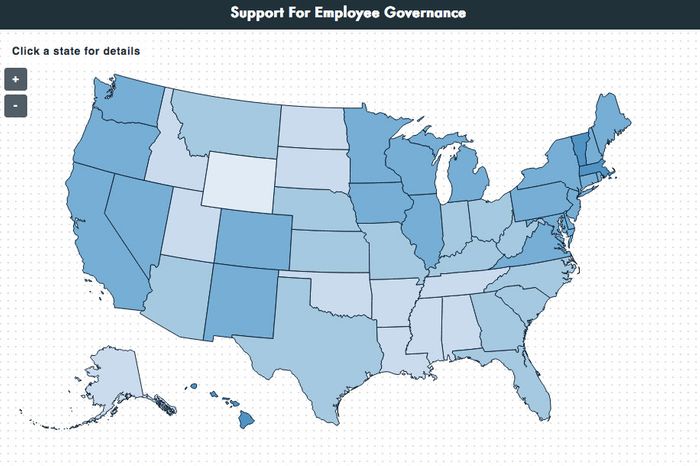

2) Workers should have representation on corporate boards.

Over the past two years, the Democratic Party’s most progressive senators have backed the idea of requiring large corporations to set aside a share of seats on their boards (proposals range from 33 to 40 percent) for their employees’ elected representatives. In other words, they’ve proposed forcing companies to give their workers some say in how profits are allocated. This arrangement, widely known as “worker co-determination,” is prevalent in Western Europe and a pillar of Germany’s economic model. Historical evidence suggests that, had workers’ representatives been in every corporate boardroom in January 2018, the Trump tax cuts might have actually trickled down to workers’ paychecks (instead of pooling in wealthy shareholders’ bank accounts). As a policy that both challenges managerial supremacy within the firm and would likely redistribute significant sums from capital to labor, worker co-determination is arguably a “far left” policy by American standards. It is also has a net-positive approval rating in every single congressional district in the United States.

3) The credit-card interest rates are too damn high.

Bernie Sanders and Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez have introduced legislation that would cap interest rates on credit-card debt at 15 percent per year. Data for Progress did not mention the names of the proposal’s co-sponsors in its poll of the policy. But it did inform respondents that “Republicans say this will hurt the economy … [W]ithout the ability to charge large interest rates, financial institutions will be unwilling to lend, and consumers will lose the ability to use credit cards when they most need it.”

Despite this partisan framing, capping credit-card interest rates attracted not just majority but supermajority support in all 50 states. The policy is most unpopular in Wyoming, where only 68 percent of voters support AOC’s vision for financial reform.

4) Government officials shouldn’t be allowed to own stocks or become lobbyists right after leaving office.

Elizabeth Warren has proposed barring members of Congress from owning individual stocks or becoming lobbyists for years after leaving office. Given that even Trump has pretended to disapprove of the “revolving door” between Capitol Hill and K Street, it is perhaps unsurprising that this proposal is popular in every state.

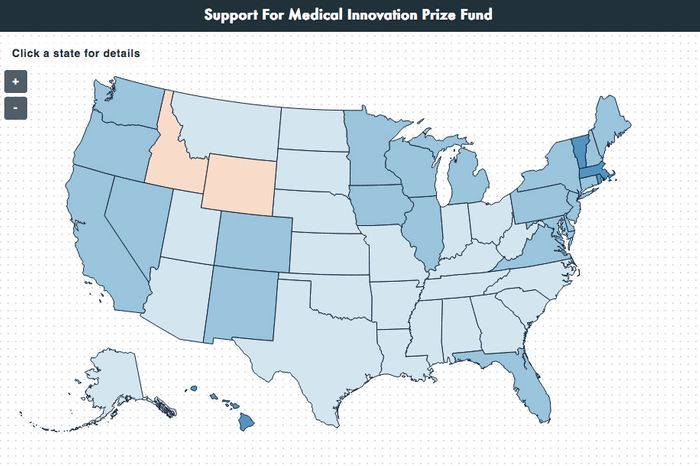

5) The government should directly finance the development of new drugs, and then allow the breakthrough pharmaceuticals to be sold cheaply without a patent.

The high cost of prescription drugs in the U.S. has prompted complaints from lawmakers on both sides of the aisle. And yet, only the most left-wing members of Congress have called for tackling the underlying problem: the way America chooses to finance pharmaceutical research and innovation. At present, the United States incentivizes drug companies to develop new cures by awarding innovation with patent monopolies; which is to say, by letting pharmaceutical firms price gouge for years before their new wares hit the free market. This is less than ideal for multiple reasons. For one, these patent protections tend to be needlessly generous, awarding Big Pharma longer periods of exclusivity than necessary to stimulate research. For another, since innovation is rewarded with a monopoly rather than a direct reward, this system does little to incentivize research into drugs that aren’t hugely profitable, either because they treat rare conditions or because they cure users with a single dose.

A better way to incentivize pharmaceutical innovation and drastically reduce the cost of new prescription drugs would be for the federal government to maintain a prize fund that awards developers of therapeutically valuable new medicines with a giant, onetime payment, on the condition that their science immediately enters the public domain, making the novel treatment available at generic rates. This proposal, championed by Bernie Sanders, has majority support in 48 states.

6) All workers should be able to take up to 12 weeks of paid time off following a serious medical injury or childbirth.

Providing U.S. workers with the kinds of paid-leave benefits that are standard in Western Europe is a longtime goal of American progressives. But some Democrats have balked at the challenges of financing such a policy. New York senator Kirsten Gillibrand’s FAMILY Act would fund 12 weeks of leave for new parents or the infirm with a modest increase in payroll taxes. Since this would constitute a tax increase on the middle class, Hillary Clinton declined to endorse Gillibrand’s legislation in 2016. But when DFP ran the policy by the American people in a survey question that mentioned the 0.2 percent payroll-tax hike and Republican arguments against the idea, the response was net positive in every state but Wyoming.

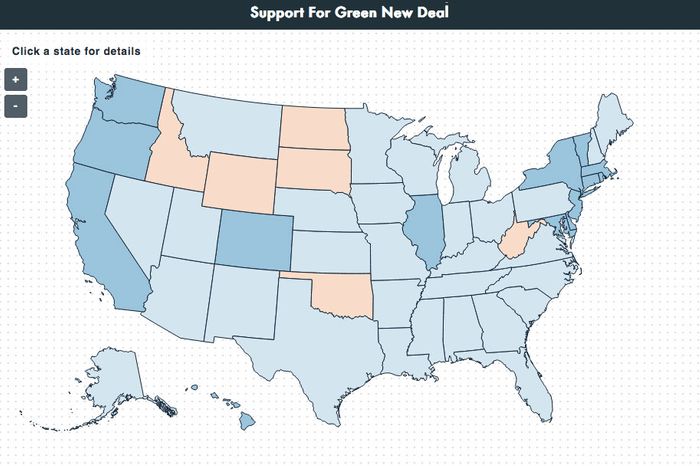

7) There should be a Green New Deal (of some sort).

Some previous polling has found broad support for Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez’s signature framework for climate policy, which combines ambitious goals for emissions reductions with a commitment to giant expansion in public employment and various other social democratic reforms. That said, in some of these surveys, a “Green New Deal” has not been clearly defined, while others have shown support for the policy withering under Fox News’ “scrutiny.” The Data for Progress poll, however, describes the concept of a Green New Deal in significant detail:

Some Democrats in Congress are proposing a Green New Deal bill which would phase out the use of fossil fuels, with the government providing clean energy jobs for people who can’t find employment in the private sector. All jobs would pay at least $15 an hour, include healthcare benefits and collective bargaining rights. This would be paid for by raising taxes on incomes over $200,000 dollars a year by 15 percentage points. Democrats say this would improve the economy by giving people jobs, fight climate change and reduce pollution in the air and water. Republicans say this would cost many jobs in the energy sector, hurt the economy by raising taxes, and wouldn’t make much of a difference because of carbon emissions from China. Do you support or oppose this policy?

A 15-point increase in the top marginal tax rate, combined with the state-mandated suppression of a major industry — and the establishment of guaranteed federal employment for every American out of work — is borderline Leninist by the standards of D.C. discourse. And yet, DFP found net-positive support for the policy in 44 states (albeit with relatively high percentages of voters opting for “I don’t know”).

Data for Progress found other ambitious progressive policies above water overall (such as lead removal), and other center-left ideas that command support in every corner of the country (such as extending the New START treaty). But the seven findings above struck me as most notable.

Taken together, DFP’s past year of polling on the “new progressive agenda” suggests the popularity of any given policy has little to do with its ideological “extremity,” as measured by conventional definitions of left and right. But it also indicates that the American public is most broadly receptive to a specific category of left-wing ideas — namely, ones that do not require major middle-class tax increases or touch on hot-button “culture war” issues. Thus, reflexively deferring to majoritarian opinion would pose significant constraints on progressive policy-making. Of the 15 proposals in DFP’s latest survey, six called for raising taxes on households earning over $200,000, and you can only go to that well so many times. Although there is reason to think the U.S. has excess fiscal space, it’s still almost certainly the case that progressives cannot fund a Nordic-style welfare state with taxes on the affluent alone. Meanwhile, there is no way of redressing racial injustice in the U.S. without advancing policies that offend red America’s sensibilities.

That said, even if Democrats were to comport themselves as cowardly, poll-driven opportunists, there’s still an awful lot that they could accomplish. For decades now, American liberalism has shied away from restructuring inter-firm relations between labor and capital, favoring an emphasis on taxes and transfers over policies that would redraw lines of ownership and authority within corporations. And yet, DFP’s survey on worker codetermination — and recent polling from YouGov and the Democracy Collaborative on worker wealth funds — indicates that there is broad, bipartisan support for helping American workers seize (a bit more control over) the means of production. A comprehensive agenda for rebalancing power within firms would arguably do more to reduce inequality than many more controversial posttax redistribution schemes. To the extent that moderate Democrats’ ambitions are tempered by fear of alienating conservative voters — as opposed to terror of offending high-dollar donors — they should consider expanding worker ownership and control of corporations to be the height of pragmatic “problem solving.”