In recent years, democracy has come to resemble a washed-up celebrity – one who achieved peak global admiration in the early 1990s, before falling from grace amid a series of scandals, unflattering exposés, and identity crises.

In other words, it’s gotten hard to contemplate democracy without thinking of Donald Trump.

The sources of liberal democracy’s declining prestige are myriad and transnational. Throughout the West, universal enfranchisement has proven inadequate to arrest the growth of economic inequality, while checks on majoritarian tyranny have failed to protect (non-plutocratic) minorities from popular bigotry. Meanwhile, China’s rising power — and conspicuous ability to implement sweeping policy changes at exceptional speed — has increased the visibility and appeal of its authoritarian model.

Democratic dysfunction in the U.S. has been especially acute. Here, gross inequities in material resources, partisan polarization, “post-truth” media, and deepening divisions over race and identity seem to have nullified the possibility of responsive government. The Republican Party’s routine betrayals of its own voters’ avowed preferences on economic policy has proven no impediment to its political dominance. Nor did the GOP’s decision to nominate an infamous con man in 2016 prevent it from securing full control of the federal government. These realities might puzzle the lay observer, but they made perfect sense to plenty of political scientists. After all, voter behavior has always been driven less by informed policy preferences than salient social identities. And in a rapidly diversifying nation founded on white-supremacist institutions, it makes sense that Republicans would have little trouble juicing the salience of white voters’ racial grievances. Whether the president supports gutting clean air laws may be more materially relevant to the median white voter’s well-being than whether the president supports the NFL’s blackballing of Colin Kaepernick, but the latter has more bearing on a cop-loving cultural conservative’s ability to feel that his people are in charge. And with Fox News and right-wing talk radio shielding the old, white exurbs from any cognitively dissonant political information, Trump’s various affronts to common decency, basic competency, rule of law, and working people have had little-to-no impact on his approval rating.

The coronavirus crisis has done plenty to highlight our polity’s ailments. America has mounted the flimsiest pandemic response of any developed country. Incompetent federal leadership prevented the U.S. from using its exceptional resources to contain initial outbreaks. A culture of contempt for expertise and nihilistic individualism has inhibited Americans’ compliance with social-distancing protocols. As a result, our COVID-19 death toll is 130,000 and rising. And our national leadership is less interested in stemming the bleeding than benumbing the public to it, confident that a nation capable of shrugging off routine school shootings can acculturate itself to a biblical plague: According to the Washington Post, White House officials “hope Americans will grow numb to the escalating death toll and learn to accept tens of thousands of new cases a day.”

But they ain’t numb yet. In fact, for all the dispiriting things that COVID-19 has taught us about our country, it’s also illuminated a few signs of civic health.

The most obvious of these is the recent drop in Trump’s poll numbers. For once, the president’s gross incompetence has had political consequences. Since the onset of the COVID crisis, presumptive Democratic nominee Joe Biden’s lead in national polls has swelled into double digits, while Trump’s approval rating has sunk near all-time lows. Even more encouraging than the national numbers, however, have been the trend lines among regions and constituencies hit hardest by the coronavirus.

Surveys from Pew Research show that the president’s approval rating has fallen fastest in the 500 counties where per capita coronavirus deaths have been highest. Pew polled a representative sample of residents from such places in late March, and then reinterviewed the same voters again in late June, and found that the president’s approval had fallen by 17 percent in the interim. Meanwhile, after favoring Republican candidates in the last five presidential elections, a wide array of national and state polls show America’s seniors leaning toward Joe Biden in 2020.

What makes these findings so encouraging from a (small-d) democratic perspective is that they suggest the direct, material consequences of bad policy are yielding informed, rational changes in voters’ allegiances. This is no small thing. It is true that macroeconomic conditions reliably influence the electoral prospects of incumbents. But some political scientists contend that adverse economic conditions don’t influence voter behavior directly; rather, they do so by increasing negative media coverage of sitting presidents. This is a significant distinction, since it would imply that, even in the context of an economic crisis, voters are unlikely to hold policy-makers accountable for the material consequences of their actions without the media’s instruction, which would be concerning since nonpartisan news outlets have been losing influence with each passing year. In fact, the rising supremacy of ideological media has coincided with a declining correlation between economic indicators and presidential approval.

The fact that Trump’s numbers are falling faster in COVID-19 hot spots than they are nationally — and faster among the old than among the general public — suggests that it isn’t media coverage alone that’s driving swing voters toward Biden, but also rational self-interest.

To be sure, the conditions that produced this outbreak of voter rationality — a world-historic pandemic, 130,000 deaths, and a president repeatedly telling the public, directly, that he has no plan for resolving the public-health crisis beyond waiting for it to “disappear” (or perhaps injecting bleach into his lungs) — are extraordinary. If this is what’s required to make the direct consequences of public policy politically salient, then that’s hardly encouraging.

Yet there were other circumstances surrounding the recent changes in public opinion. Namely, the largest outbreak of civil unrest in a generation. In cities across the country, left-wing activists mobilized against one of the most popular institutions in American life. Stores were looted, a police station was burned, and statues of Founding Fathers were vandalized. A progressive policy demand too radical for most nonwhite voters — the abolition of the police — occupied the center of national discourse for weeks.

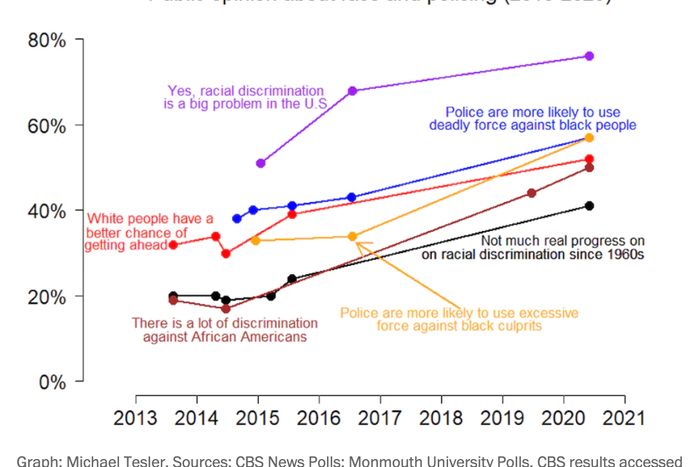

Nevertheless, to Trump’s ongoing incredulity, the silent majority’s backlash has yet to be heard. The latest culture-war skirmish has done nothing to mitigate the political costs of Trump’s pandemic mismanagement; he’s lost far more support from white voters than nonwhite ones in recent weeks. To the contrary, the emergence of police reform as an election year issue appears to have deepened Trump’s plight, as white voters have revised their views on racial-justice issues. In recent days, polls have found two-thirds of Americans voicing support for the Black Lives Matter movement (which had failed to secure majority approval during its first six years of existence), while the percentage of voters who say that “racial discrimination is a serious problem,” that “police are more likely to use deadly force against Black people,” and that “white people are more likely to get ahead” all hit record highs in various tracking polls. According to Pew, Biden boasts his largest advantage over Trump on the question of which candidate voters trust to “effectively handle race relations.”

Which is to say, Black Lives Matter hasn’t reduced the salience of Trump’s governing failures, so much as it has reduced the prevalence of white grievance within the U.S. electorate.

One must be careful about drawing sweeping conclusions from nascent shifts in public opinion. But it seems possible that the COVID-19 crisis is illuminating the preconditions for durably improving the health of our body politic. Shutdowns and social distancing have massively reduced political outlets’ competition for voters’ attention, while a life-or-death social crisis has increased media consumers’ demand for reliable, nonpartisan information. Nightly network news programs have seen massive ratings bumps, and this seems to have enabled less politically minded voters to both educate themselves on issues that they hadn’t previously given much thought and to draw connections between their lived experience and national politics.

The New York Times’ recent interviews with Trump-to-Biden voters yielded anecdotal evidence of this phenomenon:

Coronavirus also changed the mind of Ariel Oakley, 29, who works in human resources in Grand Rapids, Mich. “With coronavirus, even just watching the press conferences, having him come out and say it’s all fake,” she said. “I have family who have unfortunately passed away from it.”

It made her wonder how often he hadn’t told the truth before, she said. She plans to vote for Mr. Biden.

And the political scientist Ashley Jardina argues that a pandemic-induced uptick in news consumption lies behind white America’s awakening to racial injustice. “There has long been a constituency of white Americans who are fairly educated, many of them college educated, disproportionately women, who have been largely unaware of the extent to which people of color in the U.S. experience real discrimination,” Jardina told The Atlantic last month. “The news has their attention.”

Of course, we can’t count on pandemics to increase the American public’s civic engagement every election year (hopefully not, anyway). But the fact that heightened attention to political issues has produced more humane and rational voter preferences indicates that our democracy’s defects aren’t inherent in its people. Give Americans the tools, incentives, and institutions necessary for exercising effective self-government, and they just might redeem this sorrowful republic.