When your presidential candidate is not doing well, it’s not uncommon to look around for historical analogies in which a similarly downtrodden candidate has made a dramatic comeback to win. Until recently, Donald Trump fans needed to look no further than his own improbable victory in 2016. But now it’s beginning to dawn on Trump supporters that Joe Biden is not Hillary Clinton, the object of decades of intense demonization by conservatives, nor is the president an insurgent challenger, much as he might want to pose that way to prevent a “referendum” on his tenure in November. In addition, Biden’s polling leads over Trump both nationally and in battleground states are beginning to exceed anything Clinton enjoyed at similar points in the election cycle.

So observers looking about for an example Trump might yet emulate are going back 68 years, to Harry Truman’s upset reelection win over Thomas Dewey. Here’s Richard Lim at the Washington Examiner:

The similarities between the 1948 and 2020 elections are striking. Like President Trump, Truman often ruffled feathers with his salty language. At one point, Truman even described Dewey as a fascist, a term not taken lightly just three years after World War II.

Just as with Trump, the media described Truman as desperate and unhinged. They mocked him for the more than 8,000 empty chairs at a speech he gave in Nebraska — presaging the coverage of Trump’s recent speech in Tulsa, Oklahoma. Almost everyone thought Truman would lose, including the president’s mother-in-law.

A Newsweek poll reported 50 out of 50 politicos predicting a Dewey victory.

But on Nov. 3, 1948, the world woke up to the stunning news that Truman had won. The experts were left struggling to make sense of how they got it so wrong.

The idea that Harry Truman was basically Donald Trump without Twitter is pretty funny. And the suggestion that the experts have it all wrong now because they did so in 1948 and 2016 kind of ignores the 16 presidential elections between those two meteoric events; in most, the prognosticators got it right.

But just for fun, let’s look at the analogy more closely and see if it holds out any particular hope for Trump fans looking for a big upset. Here are some factors that fed into the 1948 shocker that might distinguish them from today’s circumstances:

There Weren’t Many “Experts” in 1948, and They Weren’t Watching Closely

The political commentariat in 1948 was wildly different, and much smaller, than today’s, centered mostly in daily newspapers. And there were only three national polling operations (Gallup, Roper, and Crossley), all utilizing a primitive version of weighted sampling called “quota sampling” that had led to serious errors in prior elections. Gallup famously quit polling weeks out from the election after “finding” a five-point Dewey lead.

There was nothing in 1948 like today’s plethora of national and state pollsters, all constantly refining methodologies and being held accountable for accuracy and transparency. And no, they are not a bunch of chumps: The myth that pollsters all got 2016 “wrong” is largely itself wrong; national pollsters on average came reasonably close to the popular-vote results, won by Clinton by just over 2 percent. By contrast, 1948’s sparse polls missed a big swing to Truman, who won the national popular vote by 4.5 percent.

Dewey Was Immensely Overconfident

Every account of the 1948 contest describes Republican nominee Thomas Dewey as an overconfident candidate who was out-campaigned by Truman and took few if any risks. It was understandable. Democrats had won four straight presidential elections under FDR and were now running an incumbent who had only been elevated to the office by his predecessor’s death. The post–World War II atmosphere seemed much like post–World War I’s “return to normalcy,” which produced a Republican landslide. It was clearly “time for a change,” and the 1946 midterms showed so, with Democrats losing 54 House seats and ten Senate seats, along with control of both chambers.

Thanks to what happened in 2016, there is probably no Democrat in the entire country who is “overconfident” right now. Until a wooden stake is pounded into the 45th presidency, the possibility of another Trump threading-of-the-Electoral-College win, or even a post-election Trump refusal to accept defeat, will keep Democrats on their toes and alert to any negative trends. Whatever his weaknesses, moreover, Joe Biden has nothing of Tom Dewey’s chilly, stiff persona, which lent itself to perceptions he just didn’t want victory enough.

Democratic Divisions in 1948 Ultimately Fueled Truman’s Comeback

One reason for Republican overconfidence in 1948 was that Truman’s Democrats entered the general election badly splintered, with break-off candidacies to the president’s left (the Progressive Party under former vice-president Henry Wallace) and his right (the States’ Rights Democrats, or Dixiecrats, under South Carolina Governor Strom Thurmond). Truman’s campaign focused intensely on reducing Wallace’s support to a bare minimum via appeals to labor and civil-rights constituencies (he won higher percentages of the Black vote than FDR had). It largely ignored Thurmond, in hopes that his purely regional appeal and southern Republican weakness would mitigate the damage to the incumbent.

The strategy worked, as Wallace and even some Thurmond Democrats began to “come home” to Truman late in the campaign, fueling his comeback. In the end, each of the “splinter” candidates got about 2.4 percent of the national popular vote; Wallace came nowhere close to carrying a state, while Thurmond won just the four Deep South states, where the Dixiecrat ticket usurped the state Democratic ballot line.

By contrast, Trump’s strength among Republicans right now means there are few natural supporters likely to “come home” in November. His weakness is among independents and conservative Democrats, who may be harder to persuade.

The likelihood that Truman had deeper reservoirs of potential support than Trump does today is also born out in job-approval-rating trends. Trump has notoriously been stuck in a narrow band of approval ratings, mostly in the high 30s to the mid-40s (right now he’s at 40.6 percent, according to FiveThirtyEight). Gallup only occasionally did approval-rating polls in 1948, but while Truman was in the 30s in the spring of that year and at 40 percent in June, by January of 1949 he was up to 69 percent (pretty much where he was in the spring of 1947). That is almost certainly never going to happen to Donald Trump.

The Condition of the Country Was Stable and Improving in 1948

While the economy was not booming in the run-up to the 1948 elections, conditions were improving. Inflation was significantly down in comparison to 1947. Unemployment was at a reasonable 4 percent, and GDP growth was running at 4.1 percent after three years of recession. Farm prices were high, which turned out to matter a great deal, as Truman swept most Farm Belt states.

We don’t know what the U.S. economy is going to look at this November (or perhaps more relevantly in September and October, when early voting begins). But current coronavirus trends do not show much likelihood that the “rocket ship” recovery Trump was talking about in early June is going to arrive before voters vote.

In 1948 as now, the United States was at peace. But in 1948, the United States was arguably at its historic peak in international power and prestige. It still enjoyed a nuclear-weapons monopoly, Truman’s Marshall Plan was beginning to reduce the specter of communism in Western Europe, and the communists had not yet won control of China. The United Nations was a functioning entity under unquestioned U.S. leadership.

By almost any measure, U.S. global prestige is now at a low point, in part thanks to Trump’s deliberate policies of nationalist unilateralism and self-isolation. Even national pride, which Trump promotes relentlessly, is at a nadir, as a new Pew survey shows:

[J]ust 17% of Americans – including 25% of Republicans and Republican-leaning independents and 10% of Democrats and Democratic leaners – say they feel proud when thinking about the state of the country.

Trump is not likely going to be reelected on a burst of good feelings about the country.

Truman Had an Active, Unpopular Congress to Run Against

In 1948, Harry Truman was largely an activist Democratic president running against a reactionary Republican Congress. While he called that Congress “do-nothing,” that was a bit of a misnomer; it was actually a productive Congress whose efforts to dismantle the New Deal were regularly repulsed by presidential vetoes (Truman would eventually veto 250 bills, as compared to eight vetoes from Trump so far). The Republican congressional threat to New Deal labor policies and agricultural programs was a constant theme of Truman’s campaign, and it paid off on the electoral map in the cities and rural areas of key midwestern states.

Congressional productivity has dropped to a low ebb during the Trump administration, whose party controlled Congress entirely during the first two years of his presidency. Since Republicans lost the House in 2018, Mitch McConnell’s Senate has been the most conspicuous source of delay and obstruction across the spectrum of policy issues. Trump himself has very few legislative accomplishments and cannot articulate a policy agenda for a second term. Even if he does emulate Truman’s barnstorming personal campaign style, he won’t have much to say other than the culture-war staples that appeal to the base he already owns.

Turnout Was Down in 1948

One reason the polls got 1948 wrong was that turnout was sharply down, reaching the lowest level between 1924 and 1996. The aforementioned Republican overconfidence is probably the most widely attributed reason for the turnout drop, though others have speculated that ethnic voter allegiances associated with World War II released their grip on key categories of voters (e.g., German-Americans). In any event, Truman’s comeback against high odds was facilitated by the fact that he was able to operate within the parameters of a smaller-than-expected electorate.

Before March of 2020, it was universally assumed this presidential election would produce very high turnout, just as the 2018 midterms did. Trump’s base of support is almost certainly limited to something near the 46 percent of the vote he won in 2016, given his reelection strategy of ignoring all voters other than his base. An expanded electorate could be impossible for him to win, particularly since minor-party voting is expected to be far down from 2016 levels.

The coronavirus pandemic, of course, has not only discouraged risky in-person voting this year but has given Republicans a new voter-suppression strategy by discouraging the utilization of very popular voting-by-mail options. Can they perhaps succeed in creating a smaller electorate in which Trump has a better chance of winning? It’s entirely possible, though again, the kind of pandemic conditions most conducive to this strategy might well wipe out swing-voter support for Trump almost entirely, giving Biden a big advantage even in a reduced and skewed electorate.

Truman Won Late on Election Night

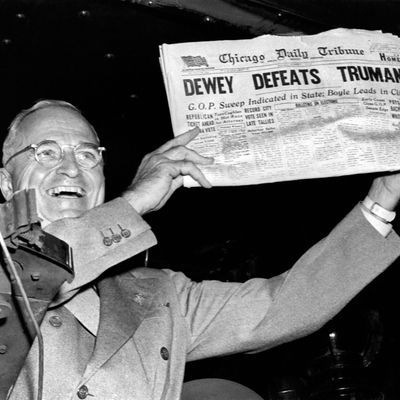

A big part of the whole mythology of 1948, encapsulated by the famous photo at the top of this piece, was that early returns on November 2 of that year showed Dewey appearing to confirm the pollsters and the pundits who predicted a GOP victory. He won no less than seven northeastern states he had failed to carry against FDR four years earlier. But when polls began to close in the Midwest and plains states, the worm turned: Truman won five states that Dewey had won against FDR. Truman also won in Illinois (28 electoral votes), California (25 electoral votes), and Texas (23 electoral votes). Dewey won a grand total of 28 electoral votes west of the Mississippi. But he was looking great early in the evening.

In the rigidly polarized environment of 2020, it’s unlikely we’ll see anything like the exchange of states the two parties executed between 1944 and 1948. The whole ball game is almost certainly going to come down to whether Trump can win the same states he won in 2016, or just enough of them to crawl over the 270-electoral-vote-majority requirement.

But if anyone gets out to an untenable early lead on November 3, it’s likely to be Trump. Thanks to his relentless attacks on voting by mail, Republicans may disproportionately vote in person, casting the first votes to be counted in most states. Hours, or days, or even weeks later, late mail and provisional ballots, which tend to skew Democratic, may wipe out early Trump leads in battleground states, if they occur at all. The high odds that Trump will make this the basis of contesting an election defeat is becoming the great scandal of this election year. But if anyone is triumphantly holding up an election-night newspaper with a premature result a day or two later as Truman did, it’s probably going to be Joe Biden.