The Democrats are “the party of the incredibly wealthy coastal elites,” while Republicans are the party of “the great American middle.” The former fight for out-of-touch “urbanists” and “woke” corporations, while the latter stand with the forgotten men and women of rural America.

If you’ve watched a Republican campaign ad or read a conservative pundit at any point in the last four years (and/or four decades), you’ve heard some iteration of this message. Anti-metropolitan populism is as ubiquitous in GOP rhetoric as salt is on French fries. In fact, Republicans are so unabashed in their rural chauvinism that they routinely argue that America’s political institutions should not give equal representation to people who live in cities. Just last year, Tom Cotton argued that Washington, D.C., does not deserve Senate representation because, while it may be more populous than Wyoming, “Wyoming is a well-rounded working-class state,” while D.C. is a city of “bureaucrats and other white-collar professionals.”

All of which makes the current sticking point in negotiations between Democrats and Republicans on infrastructure a bit remarkable: While Joe Biden would like to finance new infrastructure by raising taxes on wealthy corporate shareholders (who disproportionately live in large coastal cities), moderate Republicans are demanding that he “pay for” new roads and bridges by raising taxes on Americans who drive a lot (who disproportionately live in rural areas).

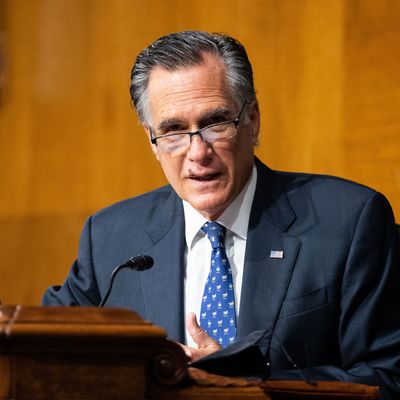

Republican senators Shelley Moore Capito and Mitt Romney said this week that they are working with eight of their GOP colleagues on a counteroffer to Biden’s $2.25 trillion American Jobs Plan. According to Capito, the Republican proposal will depart from Biden’s in three main ways: It will narrowly focus on physical infrastructure (whereas Biden’s plan includes investments in green technology and eldercare), it will cost between $600 billion and $800 billion, and it will be financed through “user fees” — which is to say, a gas tax and “vehicle miles traveled” (VMT) tax. For his part, Romney told Politico Wednesday that $800 billion sounded “a little high.” But he seconded Capito’s commitment to user fees, which Mississippi senator Roger Wicker has also endorsed.

The GOP’s commitment to soaking its own base is more of a deal-breaker than the party’s call for a slimmer package. After all, Democrats still have two more reconciliation bills in their quiver, and Biden already planned to enact his “Build Back Better” agenda in two parts. So, the president could simply pass a conventional infrastructure-only bill with Republican support, then get the rest of the American Jobs Plan into law through future legislation. By contrast, approving a gas-tax hike would require Biden to violate a campaign promise: In 2020, the president vowed that he would not raise taxes on the middle class. On Tuesday, Biden formally ruled out that possibility in talks with moderate Republicans.

To appreciate the oddity of the Republican position, consider which Americans would lose the most income to a VMT and which the least:

Then, contemplate which Americans have the most to lose from Joe Biden’s tax plan:

Finally, consider that more than 90 percent of America’s highest-earning one percent live in metropolitan areas, and that the bulk of those 90 percent live in coastal metros.

Put all this together and a plain fact emerges: Joe Biden is trying to make wealthy coastal elites pay for roads and bridges in the heartland, while Republicans insist on imposing a de facto carbon tax on those “well-rounded, working-class” Americans in Wyoming instead.

As a substantive matter, I personally think there’s much to be said for raising the gas tax and establishing a VMT. If you believe that climate change is a crisis and reducing emissions is a priority, then making driving more expensive is a worthy goal. Of course, such a policy could be regressive if adopted in isolation. But if progressives wish to bring social democracy to the U.S., we are eventually going to need to support raising taxes on working people, so as to sustainably finance public programs that disproportionately benefit them.

But I don’t think Mitt Romney or Shelley Moore Capito believe any of those things.

To be fair to Senate Republicans, it seems possible that no more than a handful of them are earnestly advocating for raising taxes on rural commuters. Although there is a group of 10 moderate Republicans who’ve been negotiating with the White House over infrastructure, they have yet to produce any alternative proposal — perhaps because they’ve yet to find one that all of them can support.

Meanwhile, as Benjy Sarlin explains for NBC News, Republican strategists are already planning to attack Biden as a persecutor of heartland drivers, should he prove dumb enough to meet their party’s demands:

Republicans outside the negotiations are eagerly telegraphing how they plan to run against their proposed pay-fors. A strategy memo by Senate Republicans on how to oppose Biden’s plan cited polling showing opposition to a gas tax. When members of the Biden administration even mentioned a gas tax or VMT as a hypothetical, Senator Rick Scott, who chairs the NRSC this cycle, leapt to attack them in press releases and interviews.

In short, Republicans are (potentially) offering Biden less money, a less popular tax, and the opportunity to get deluged with negative ads citing their own ideas courtesy of their colleagues in exchange for a (possible) sheen of bipartisanship.

The bipartisan negotiations over infrastructure should probably be understood as a work of theater. Democrats might be willing to make concessions on spending — but only if they can undo those concessions in a subsequent reconciliation bill. Some Republicans, meanwhile, might be willing to support a gas-tax-funded highway bill — but only if their party can then attack Joe Biden for raising gas prices in subsequent campaign ads.

The idea that Democrats serve the interests of the urban rich while the GOP serves those of the rural working class is a lie. But the two parties do genuinely have very different priorities. Democrats want to raise working-class incomes and promote sustainable development in rural and urban areas alike; Republicans want to maximize the one percent’s after-tax earnings and make Joe Biden a one-term president. It will be hard to find a compromise that reconciles these objectives.