We’re entering an age of economic upheaval. Robots were already coming for workers’ jobs before the pandemic, and COVID hastened their arrival: To comply with public-health protocols while keeping pace with demand, firms have deployed automation in warehouses, grocery stores, call centers, and manufacturing plants. Meanwhile, a profusion of breakthrough technologies — from AI to quantum computing to bioscience — is poised to transform our economies in ways we can’t fully anticipate. Add to this the twin imperatives of phasing out fossil fuels and keeping pace with a rising China in the high-value industries of tomorrow, and it’s clear the economic challenges of the 21st century are fundamentally different from those of the 20th. A new era requires new ideas, not nostalgic reassertions of postwar verities.

Or so one often hears.

Earlier this month, Tony Blair rehearsed a version of this argument in an essay for The New Statesman, in which he declared that the world is “living through the most far-reaching upheaval since the 19th-century Industrial Revolution.” In this new context of “technological revolution,” the former U.K. prime minister explained, the left’s “old-fashioned economic message of Big State, tax and spend … is not particularly attractive.”

It’s certainly true that much policy thinking — across the left, right, and center — gives too much weight to past experience and too little to novel conditions (for example, the boomers’ formative experience with stagflation still haunts America’s macroeconomic debate nearly a half-century later). But in the United States, the anti-traditional, pathbreaking policies necessary for meeting the challenges of the 21st century are, in large part, the “old-fashioned, tax and spend” policies of Europe’s 20th century. Unfortunately, reforms that were banal in the Scandinavia of 1960 remain utopian in the U.S. of 2021.

The American worker is not all right.

A new McKinsey survey on economic opportunity in the U.S. drives these points home.

In March and April, the consulting firm interviewed 25,000 Americans about their economic hopes and the obstacles they face in achieving them. Among the survey’s key findings:

• Inadequate access to affordable health care was the most commonly cited barrier to well-being, with one-third of respondents naming it as a top-three obstacle.

• Half of those surveyed would not be able to cover their living expenses for more than two months if they or someone in their family lost a job (and 34 percent of respondents had lost a job or income over the past year).

• More than 60 percent of gig-economy workers would prefer a full-time job.

• Only 43 percent of women consider child care “affordable,” and more than one in four women are considering exiting the labor market or “downshifting their career” as a result of the pandemic. Unsurprisingly, women are less optimistic about their economic future than men are.

• Fifty-five percent of workers who are interested in pursuing training, education, or a credentialing program cited the cost of such endeavors — in tuition and/or lost wages — as a barrier.

These results are unsurprising. And to a great extent, the discontents they illuminate are the downstream consequences of America’s underbuilt welfare state.

Missed opportunities in America’s past are limiting economic opportunity in its present.

World War II and the golden age of economic growth that followed it offered nations across the West an exceptional opportunity for establishing durable social-democratic institutions. The mass mobilization required for total war facilitated the growth of organized labor and cultivated a cultural sense of collective interdependence. The conflict’s destruction of wealth — and, in France and Germany, its discrediting of collaborationist elites — significantly eroded capital’s political and economic dominance. Meanwhile, the imperative to demonstrate capitalism’s superiority to the (then-formidable-looking) Soviet model led many right-leaning elites to embrace redistributive reform. Finally, the high rates of growth fostered by wartime innovations and postwar rebuilding lowered the contradictions between capital and labor: High profits for business owners were compatible with expansive social benefits for workers.

But the U.S. missed the boat. This was partly because of our relative insulation from the war’s devastation (we had few Nazi collaborationists in our capitalist class and no firebombed cities to rebuild) and partly because of peculiar aspects of our political economy (an archaic constitution that makes legislation exceedingly difficult to pass, an exceptionally powerful capitalist class and weak federal state, a racially divided labor movement, a white-supremacist South, etc.).

Instead of a proper welfare state, the U.S. built an employer-based system of social provision. Large, immensely profitable manufacturing firms bargained with trade unions over health care, leave, workers’ compensation, and other benefits, and their compromises became industry standards. Child care was not publicly funded but, rather, was left to women and kinship networks, who were, ideally, supported by the “family wage” of a male breadwinner. The employer-based core of this social model was eventually supplemented by vital public programs, from Medicaid to Head Start. But “Big Government” in the U.S. never approached the scale and ambition of the Western European welfare state.

As a result, the American social model became obsolete long before robots started serving hamburgers. America’s labor settlement had unraveled by the 1970s as foreign competition thinned U.S. manufacturers’ profits. In Western Europe, labor’s postwar gains were typically enshrined in public laws and institutions; in the U.S., they were predominantly written into discrete collective-bargaining agreements. Thus, those benefits became the entitlements of a single generation of select workers, rather than of American citizens in perpetuity.

The postwar approach to child-care provision held up little better. As working-class wages declined, women began entering the workforce in larger numbers. As workers increasingly sought employment in cities far from their ancestral hometowns, the costs of child-rearing were less easily socialized through kinship networks. The right’s success in blocking progress toward universal child care under Nixon left American women with the dual burdens of breadwinning and care; according to McKinsey, in 2020, women were still performing twice as much unpaid care work as men in the U.S.

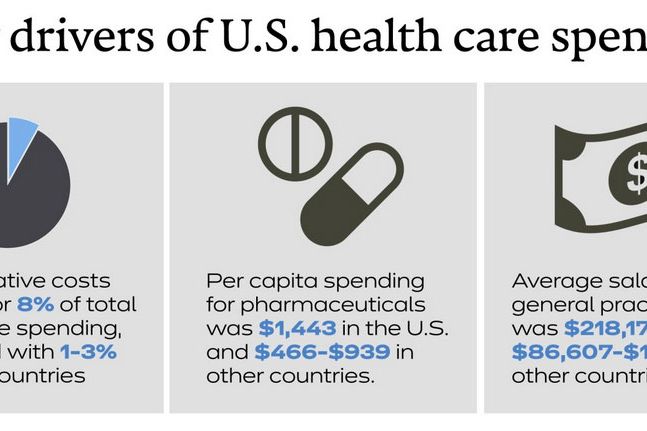

Meanwhile, the failure to socialize medicine allowed a private health-care industry to entrench itself. Union contracts and public programs subsidized (some) Americans’ health-care spending. But Uncle Sam imposed few cost controls on the sector. American hospitals, doctors, and pharmaceutical companies were therefore able to secure payment rates far higher than their foreign peers were. With demand supported by the government but prices left largely to private discretion, the health-care sector managed to eventually commandeer nearly one-fifth of the U.S. GDP. The industry’s extraordinary size makes it extraordinarily difficult to reform. Not only can the sector’s rentier interests afford to inundate the airwaves with anti-reform propaganda, but they can also claim — credibly — that any attempt to bring prices down to international standards will force job losses and wage cuts on one of the nation’s largest industries.

Where there’s no political will, there’s no way.

The coming economic upheaval, as described by the likes of Tony Blair, is a mere exacerbation of existing economic realities. The challenge of the present is to ensure that working people have a comfortable standard of living despite routine labor-market disruptions, ecological decline, growing automation, and weak (and rapidly shifting) consumer demand. If we presume that the “technology revolution” will unfold as Blair prophesizes, the challenge of the future will be much the same.

How do we guarantee Americans affordable health care in a context of routine job displacement and labor-market churn? Well, we can follow the lead of every other developed country and have the state guarantee universal coverage through large “tax and spend” programs and top-down price controls. How do we ensure that displaced workers can cover their living expenses for more than two months as they seek retraining or new jobs? We could make America’s (regular, non-pandemic-era) unemployment benefits as generous and long-lasting as those in the median OECD country:

How can we address the involuntary underemployment of gig-economy workers while redirecting ambitious low-skilled workers toward new, high-productivity occupations? We can make part-time employment more appealing by providing gig laborers with the full suite of social benefits enjoyed by their Nordic peers while offering state-subsidized job retraining and/or higher education for those interested in full-time, high-skill employment.

How do we make child care affordable for families and enable women to fully participate in the economy? We can bring U.S. federal spending on child care and early education up to European levels.

Or rather, we can do these things in theory: In practice, the U.S. appears politically incapable of doing any of them.

Joe Biden’s jobs and family plans would constitute real improvements to the status quo, but they would still leave the U.S. with an austere welfare state by international standards and do little to address America’s health-care crisis. One recent poll found that a supermajority of voters believed “health-care costs” should be Congress’s top priority. But the electorate also punished Barack Obama and Bill Clinton for pursuing major health-care reforms, so Biden is steering clear of the issue.

All signs suggest that whatever makes it through Congress will be far more modest than Biden’s proposals. Durably financing a comprehensive welfare state would require raising taxes across the board; moderate Democrats don’t even have the stomach to tax the unearned capital gains of millionaire heirs.

The U.S. is not without its strengths, of course. In many respects, our nation is better situated to thrive in the coming century than the European Union is. Our vast collection of research universities is peerless. Our tech industry is a world leader. Our central bank is less wedded to austerity than Germany’s. Our relatively high tolerance for immigration makes our demographic crisis less acute. We are, in the aggregate, extremely rich. All this gives us the material capacity to construct a new era of shared prosperity.

Yet the outlook for radical reform is as bleak today as it was auspicious in the postwar era. Labor is disorganized. The GOP coalition is wildly overrepresented in Congress. The Democrats are feckless. Our economic future is less imperiled by technological upheaval than political inertia.