As observers tensely awaited potential landmark decisions on abortion and guns, on Tuesday the conservative majority of the U.S. Supreme Court took a big step on another contentious subject. In a 6-3 decision, the Court expanded its new doctrine that ensuring the constitutional “free exercise” of religion is more important than policing the document’s prohibition on the “establishment” of religion. In Carson v. Makin, Chief Justice John Roberts, backed by the other five members of the Court’s conservative bloc, held that a Maine program providing subsidies for private schools acting as public schools in remote areas of the state could not exclude religious schools as recipients of the funds.

Roberts argued that a “neutral benefit program in which public funds flow to religious organizations through the independent choices of private benefit recipients does not offend the Establishment Clause.” The principle that the First Amendment’s prohibition on making any law “respecting an establishment of religion” applies only to the most blatant government favoritism toward religion led the Court to rule in two recent cases (one involving a Missouri law regulating state subsidies for playground equipment and another concerning a Montana private-school voucher program) that religious schools could not be excluded from public benefits extended to secular private schools. But the peculiar nature of the Maine school-subsidy program makes this latest decision the potential foundation for a new doctrine requiring, as a matter of constitutional law, that any aid to elementary or secondary education, public or private, must make accommodation for religious schools. Or so fears Justice Sonia Sotomayor in her dissent:

Today, the Court leads us to a place where separation of church and state becomes a constitutional violation. If a State cannot offer subsidies to its citizens without being required to fund religious exercise, any State that values its historic antiestablishment interests more than this Court does will have to curtail the support it offers to its citizens.

While “separation of church and state” is the time-honored manner of describing how to enforce the Establishment Clause, it is no longer subscribed to at all by many conservatives, as evidenced in January, when Justice Neil Gorsuch referred to “the so-called separation of … church and state” in oral arguments in another case. Indeed, the conservative evangelicals who were once the most adamant defenders of the “wall of separation” (it was on the behalf of Baptists that Thomas Jefferson first deployed that metaphor in 1802) now routinely dismiss it and interpret the Establishment Clause as simply prohibiting favoritism toward particular faith communities.

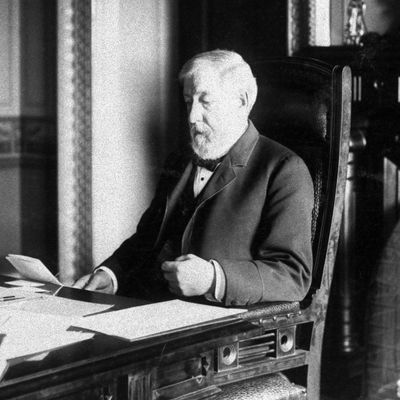

All in all, Carson v. Makin may represent only a measured extension of a new and alarming approach to “religious liberty” that Court conservatives embarked on in the Missouri and Montana cases. But its destination looks pretty radical from a longer perspective. It adds a bit of symbolic weight that the latest case arises from Maine, whose most distinguished statesman was the former U.S. House Speaker, senator, secretary of State, and 1884 Republican presidential nominee James G. Blaine. Blaine’s most enduring legacy was a proposed constitutional amendment explicitly banning the use of public funds for religious schools. It was never enacted federally, but 37 states added “Blaine Amendments” to their own constitutions. One of them clearly fell in Espinoza. Others will soon be rooted out. And Blaine (along with Jefferson) is likely rolling in his grave.

More on the supreme court

- The Supreme Court Seems Poised to Rule Against Trans Minors

- Making Sense of Joe Biden’s Supreme Court Reform Plan

- Did the Supreme Court Kill Every Case Against Trump?