On August 27, 1932, presidential candidate Franklin Delano Roosevelt stopped in Sea Girt, New Jersey, to deliver an address on an important campaign issue. “It is increasingly apparent that the intemperate use of intoxicants has no place in this new mechanized civilization of ours,” he told the crowd. “In our industry, in our recreation, on our highways, a drunken man is more than an objectionable companion; he is a peril to the rest of us. The hand that controls the machinery of our factories, that holds the steering wheel of our automobiles, and the brains that guide the course of finance and industry should alike be free from the effects of overindulgence in alcohol.” But, he continued, in most of the country, alcohol prohibition was nevertheless a “complete and tragic failure” and, as president, he promised to see it to a close, which he soon did. Although voters had been strongly split on the issue, the U.S. had to rewrite the very Constitution to do it, and we still suffer from alcohol’s social ills, the nation remembers the end of Prohibition as an unalloyed triumph of democracy and wise leadership.

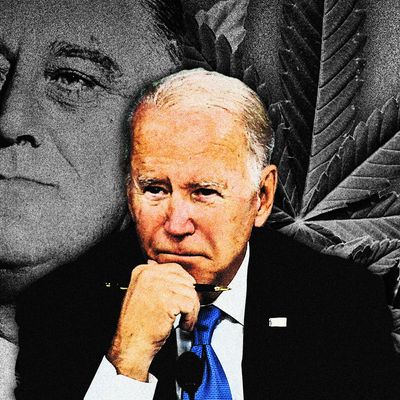

As President Joe Biden contemplates ending a prohibition of his own, he ought to keep FDR’s example in mind. Biden does not want to legalize weed. The erstwhile drug warrior has a well-known family history of substance abuse, and while the strong national consensus on marijuana has pulled his position along — Biden no longer claims it is a “gateway drug,” for example — his administration has failed to show leadership on the issue. Democrats, headed by Pennsylvania’s U.S. Senate candidate John Fetterman, are now publicly pleading with the president to exercise his executive authority to issue a decriminalization order, but Biden is wary of lending the national stamp of approval to pot — as if to do so would make him responsible for every smell complaint, teenage burnout, and drugged-driving crash that follows. Yet in the face of an annual alcohol-casualty toll that no one claims marijuana will come anywhere close to matching, Americans do not fault Roosevelt for the Beer and Wine Revenue Act, and there is no constituency for reviving the 18th Amendment. Rather, Prohibition remains synonymous with state overreach and foolish policy.

So far as we’ve had one, the national marijuana debate has focused on the merits for weed legalization: its large potential economic benefits compared to the small projected health costs. But when future generations look back at this era, they’ll see this as the second of two in a set of prohibitions coming to an end.

There is no sense in my repeating the poll numbers that show overwhelming support for an end to marijuana prohibition. Presidents Obama and Trump punted on the issue, mostly leaving it to states to flout the federal code if they felt like it — and many have. As a result, lots of Americans can now walk to their local shop and buy a bag of weed, but the shops are stuck operating in a bad-faith agreement with federal bank regulators. And smokers in less friendly states are still subject to incarceration at the whim of local law enforcement — a perfect recipe for injustice and cynicism.

The American public understands alcohol prohibition to have been badly formed on a fundamental level: To ban such a popular minor vice was to promote scofflaw-ism and its concomitant attitudes. If the president wants to see the rot of marijuana prohibition, he need only ask around the office. The workers who make his White House run have to navigate an especially tricky set of prohibition rules themselves, and the easiest way to do that is to fib. Between California, Virginia, and Washington, D.C., nearly a quarter of federal employees work in jurisdictions where cannabis is legal. But Ronald Reagan’s Drug-Free Federal Workplace order, which defines “persons who use illegal drugs” (even during their off-hours and weekends) as “not suitable for federal employment,” is still in effect. In D.C., where I live, weed is legal everywhere except on federal property, and the city’s many federal employees who smoke but aren’t allowed to admit it are forced into little green lies.

There’s a growing — and experience-derived? — understanding among policymakers that popping a gummy on Friday night doesn’t make anyone unfit for work on Monday morning. Earlier this summer, the Washington, D.C.’s city council unanimously agreed on a worker’s right to smoke while off the job, but federal employees are exempt from the protection. At the same time, the White House medical unit has been accused of operating a “grab and go” pharmacy where staffers can get prescription drugs, including the stimulant Provigil, without any questions. There’s a reason FDR singled out “hypocrisy” as a vice of prohibition — one that constituted its own type of moral intemperance: Better a nation of honest stoners than one of pill-popping hypocrites.

When it comes to staffing a government, a thin yet total restriction on weed use is a big obstacle to recruiting highly skilled tech workers, who can get paid way more to go anywhere else and who, as a group, have a disproportionate interest in both weed and contractual honesty. Software developer Jacob Kaplan-Moss was compulsively truthful enough to mention his college marijuana use in his background check for his gig at 18F, an in-house government technology and design consultancy. As he reported in a 2021 blog post, that didn’t keep him out of the job. But for others, he writes, “Expect to be asked to commit to ceasing use during your employment. You might not be, but it seems like it’s increasingly common. If you can’t keep that commitment, I’d recommend not applying.” This is not what the infosec recruiters in U.S. intelligence want to read. As FBI director James Comey once complained: “I have to hire a great workforce to compete with those cybercriminals, and some of those kids want to smoke weed on the way to the interview.”

I’m not an expert in personnel management, but it does not strike me as a good idea to hire people for important government jobs (which may well have national-security components) by inducing them to lie. One problem with the Reagan policy in the age of legal weed is that people who don’t feel comfortable lying all the time about something insignificant won’t work for you, while those who do will. An employee who begins their public service with this kind of wink-wink fraudulence may very well be less reliable than one of Kaplan-Moss’s radically honest coder friends who, though they might only smoke occasionally, would never sign a document promising not to. At a certain point, the whole thing becomes ridiculous. On August 22 of this year, the Forest Service issued a memo on marijuana reminding workers, “All Forest Service employees must remain drug-free and refrain from illegal drug use whether on or off duty regardless of state laws.” Subjecting any ranger suspected of getting high on the weekend to high-stakes drug testing is silly; it’s lucky teachers aren’t federal employees or we’d have to shut the whole country down.

At its last convention, in June 2022, the American Federation of Government Employees adopted a resolution to “Support Deleting Responsible Off-Duty Marijuana Usage from Suitability Criteria,” putting the Democratic president on the same side as dead Ronald Reagan. Biden is now the stubborn coach in Dazed and Confused — willing to lose top players in the name of prohibition. After so many years hemming and hawing about the dangers of weed, politicians like Biden might feel stuck in their position, but there’s a lot of good evidence that the public would be willing to overlook the flip-flop. Biden, recall, was instrumental to the Obama administration’s stumbling about-face on gay marriage that, though it was awkward and visibly political, still stands as a civil-rights achievement. The president’s recent decision to move forward with student-loan forgiveness and reform by executive order was contentious and maybe even disliked among policy professionals, but the people love it, and the move helped drive the administration’s popularity out of the gutter. Given its wide support, ending marijuana prohibition could have a similar effect.

When Congress received Roosevelt’s call to legalize beer, which commenced the end of Prohibition, the clerk reading it aloud “was constantly interrupted by bursts of cheers and applause from both the membership and the galleries,” a reporter wrote. “Impatient members in the back rows of the House started a chant of ‘vote, vote, we want beer.’” Biden has a chance to put his name next to Roosevelt’s in the history books, and he already has the rhetoric available to explain the decision. If the president decides to take that leap, he should do away with Reagan’s rule at the same time and release his staff, along with the rest of the country, from the intemperate hypocrisy of prohibition.