The typical voter’s political views are influenced by both their age and generation. Historically, as Americans have exited late adolescence, settled down, and developed back pain, they’ve gotten a bit more conservative. And yet, even as the U.S. electorate has gotten older, the country has not grown more Republican, since America’s rising generations are much more liberal than their predecessors: An American born in 1988 or 1998 is much more likely to vote for Democrats and hold left-wing issue positions than one born in 1958.

The future trajectory of American politics therefore hinges, in no small part, on whether millennials and zoomers will age out of their exceptional liberalism. Some political scientists contend that “cohort effects” overwhelm “age effects”: Like most other aspects of a person’s identity, political attitudes and affiliations are shaped during one’s formative years and are resistant to change later on. The median millennial perceived the GOP as hostile to their cultural values and social loyalties during adolescence. Although aging may attenuate their liberalism — and changes in issue salience or partisan positioning could shift their voting patterns — in the typical case, their basic political attitudes will endure over time.

Last month, a study of the 2022 elections lent credence to this view. Analyzing voter file data, the Democratic firm Catalist found that millennials and zoomers cast more than 60 percent of their ballots for Democratic candidates in last year’s midterms; in 2016, millennials actually gave a slightly smaller share of their votes to Hillary Clinton. This was especially remarkable, since midterms under Democratic presidents tend to see disproportionately high Republican turnout. That millennials voted more Democratic in Biden’s first midterm than they had in 2016 appeared to indicate that aging effects were essentially nil: Millennials were becoming no more conservative (and, perhaps, even a bit more liberal) as they got older. Which would suggest that generational replacement is poised to devastate the conservative movement.

Alas, the New York Times analyst Nate Cohn warns that the “emerging Democratic majority” on the horizon may be a mirage. Contrary to some recent reports, Cohn said millennials have in fact been moving right as they’ve aged; this reality has just been disguised by the changing composition of the millennial electorate. The millennial voting bloc of 2022 is not the same as that of 2008, as “six additional years of even more heavily Democratic millennials became eligible to vote” after Barack Obama’s initial election.

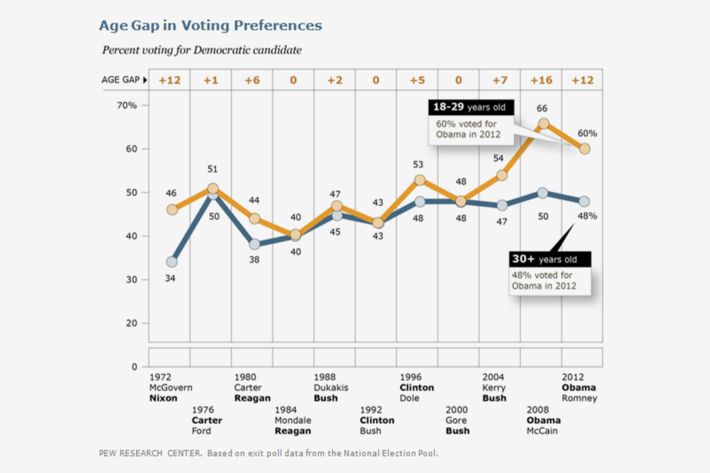

In their youth, older millennials (i.e., those born between 1981 and 1989) had produced the largest age gap in the modern history of U.S. elections: In 2008, voters under 30 were 16 points more Democratic than those over 30.

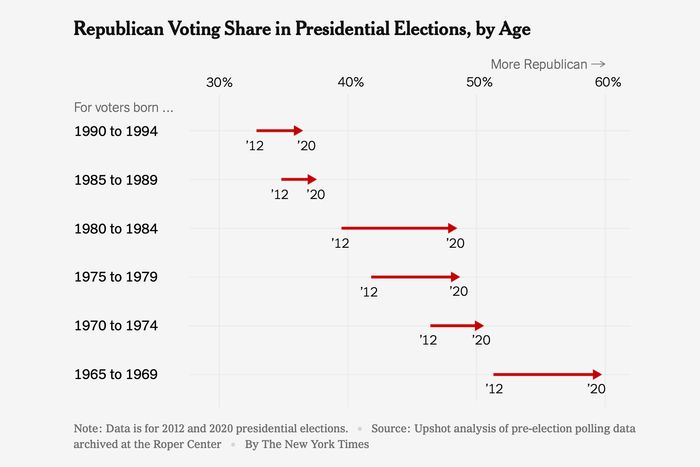

But between the 2012 and 2020 elections, these millennials became more likely to vote Republican (and this was especially true of those born before 1985):

Given that Donald Trump was a uniquely unpopular Republican standard-bearer, it’s plausible that GOP inroads with older millennials could have been even larger had they nominated a more ordinary Republican. Cohn therefore notes that if Trump is once again nominated in 2024, the coming presidential election could resemble the 2012 election, “a fleeting moment of political stability that allowed incremental demographic and generational shifts to seem to carry the day,” before cracks in the Democratic majority’s foundations began to show.

After the Obama-Romney race, many pundits declared that America had entered a new era of Democratic dominance, as an ever-diversifying electorate nudged the GOP toward political irrelevance. But this idea was premised on the assumption that the Democratic Party’s support with white working-class voters would not fall any further. And that proved to be a flawed assumption. In hindsight, it’s clear that Mitt Romney’s peculiar lack of appeal to that demographic mitigated the Democrats’ growing troubles with it. Once a more congenial Republican nominee came along, an indispensable segment of Obama’s midwestern coalition turned right. Thus, once Trump finally exits the scene, older millennials exit blue America and unravel the “emerging Democratic majority,” just as white working-class voters did before them.

This is an intriguing possibility. And Cohn’s observation that older millennials have in fact been moving right as they age is important.

Nevertheless, the implications of this development should not be exaggerated. Millennials of all ages remain more Democratic than their elders, and among all but the very eldest millennials, this gap is massive, with those born after 1984 giving much less than 40 percent of their votes to Republicans.

Critically, millennials are also much more Democratic than their predecessors were at the same age, as the chart above on the age gap in recent U.S. elections makes clear. And this exceptional partisan distribution is rooted in the generation’s distinctive social values, which do not typically change drastically over time.

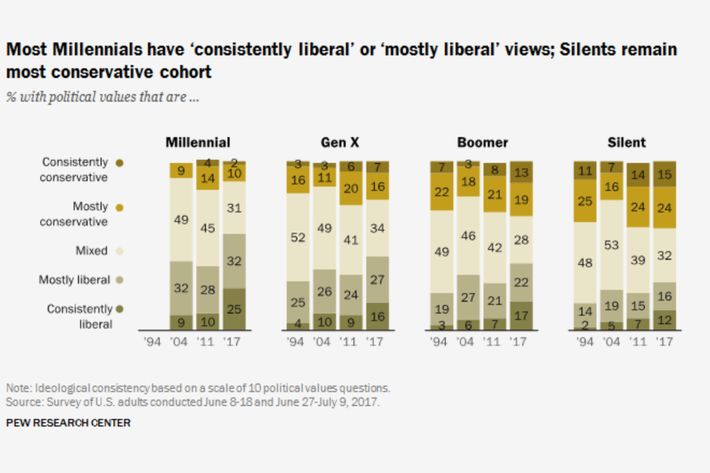

As Pew Research’s tracking survey on ten political values shows, millennials have long been exceptionally liberal, and this is especially true of the generation’s younger cohorts.

The distinctive nature of the cohort’s politics can be seen in myriad issue polls. This 2013 Pew survey on same-sex marriage illuminates an especially stark generational gap:

But the divergence can also be seen on abortion, immigration, climate change, universal health care, marijuana legalization, among many other issues.

Millennials and zoomers’ nonpolitical (or, perhaps, pre-political) attitudes are similarly distinctive. For example, they are much less likely than boomers and members of the silent generation to say that “patriotism,” “belief in God,” and “having children” are very important to them.

All of these attitudes currently correlate with those of Democrats writ large. What’s more, since parenthood tends to be one major driver of age effects (people tend to get a bit more conservative when they have kids), lower birth rates among millennials may limit the impact of aging on their politics.

The distinctive political leanings of millennials and zoomers are also, of course, related to their distinctive ethnic composition. While 72 percent of U.S. boomers are non-Hispanic white, that figure is closer to 50 percent for millennials and zoomers. As recent elections have demonstrated, non-white voters are not uniformly or immutably Democratic. But it is nevertheless the case that American politics is highly racially polarized, and that the Republican Party as currently constituted would not be competitive in a world where only half of U.S. voters were white (in 2020, 72 percent of voters were white, and roughly 56 percent of white voters backed Trump).

None of this necessarily means that younger millennials won’t follow the same political trajectory as older ones and inch rightward over time. Nor does it mean that the Democratic Party is destined to become politically dominant as millennials increasingly replace boomers in the electorate. But generational churn will absolutely change the nature of American politics and push it leftward in various respects. Age effects do not erase cohort effects. An unprecedentedly non-white and secular generation, which came of age in an exceptionally socially liberal era, is never going to have the same politics as a predominately white, highly religious generation, which came up in a socially conservative time, no matter how old the former grows.

This does not guarantee the GOP’s political extinction for at least two reasons: (1) Political parties often change their issue positions in response to persistent electoral defeat, and (2) it is possible that the issues that most divide Republicans from millennials will diminish in salience over time.

To an extent, we’ve already seen the Republican Party making ideological accommodations to the rising generations. Although Anthony Kennedy had to drag the GOP kicking and screaming into retreat on same-sex marriage, the party has largely reconciled itself to the institution and concentrated its anti-queer energies on trans issues. Cohn hypothesizes that this might partly explain older millennials’ rightward drift, as gay marriage was one of the right’s defining issues in the late Bush years, when the cohort voted more overwhelmingly for Democrats.

If generational replacement will not automatically doom Republicans, however, it will make their party’s commitment to reactionary social politics and upward redistribution increasingly untenable. It is unlikely that the GOP will be able to remain competitive with a predominantly millennial and zoomer electorate while supporting national abortion bans and opposing renewable energy. Middle age will not turn the median millennial voter into a pro-life, anti-LGBT enthusiast of rolling coal. The GOP may well be electorally formidable 20 years from now. But many of the policy goals that presently define it will (almost certainly) be political nonstarters in 2042, no matter how old, cranky, and uncool millennials become.