There is an important inflation debate that pits many mainstream economists against heterodox progressives. That argument concerns how policymakers should respond to today’s elevated rates of price growth.

Prominent economists like Larry Summers have contended that the Federal Reserve must engineer much higher unemployment in order to quell inflation.

Progressives (among others) reject this idea. Their precise reasoning varies. But most insist that Summers and like-minded economists underestimate the costs of managing inflation through engineered recessions and overestimate the risks that the labor market poses to price stability. They further argue that we should develop new mechanisms for managing and preventing inflation, ones that don’t concentrate the burdens of adjustment on the most vulnerable workers in the U.S. economy. In my view, their case is strong.

But there is another, less important inflation debate with broadly similar battle lines. This other argument concerns the causes of post-COVID inflation.

Here, mainstream economists argue that today’s inflation was born out of a mismatch between demand and supply. The pandemic recession reduced the global economy’s productive capacity by shuttering factories, disrupting supply chains, and nudging many older workers into retirement. At the same time, a series of historically large relief packages increased U.S. consumers’ purchasing power. Virus-averse consumers then shifted their copious disposable income away from in-person services and toward goods en masse. Demand for myriad manufactured products therefore soared while supply fell. This enabled producers to command higher prices for their wares. And it also encouraged them to rapidly expand production by hiring more workers, thereby pushing up the cost of labor. This, in turn, increased costs for providers of services like childcare facilities, physical-therapy clinics, and fast-food restaurants. A general and persistent increase in prices ensued.

Some progressives suggest that this account is all wrong: Today’s inflation has little to do with fiscal policy or demand conditions. Rather, it is the product of a frenzy of profiteering in the corporate sector. In my view, their case is weak.

More precisely: There is a crude version of the “greedflation” argument that is obviously wrong, and a sophisticated version that is plausible but unproven (and which does not actually refute the relevance of demand conditions). In either case, the left’s account of what caused inflation is far less compelling than its prescriptions for managing price growth.

It seems unwise, therefore, for progressives to tie the two together. Making the case against engineered recessions, or for alternative price-management tools, does not require proving that corporate profiteering caused inflation. Dwelling on the latter claim mostly serves to render the heterodox perspective on macro policy more vulnerable to critique.

You don’t cause inflation by benefiting from it.

The crude version of the greedflation argument, as articulated by former Labor secretary Robert Reich and The Lever, goes (roughly) like this: The relationship between the demand for, and supply of, goods and services has little to do with inflation. Rather, rising prices are a product of excess corporate power. As Reich writes, “Corporations have the power to raise prices without losing customers because they face so little competition.” And they face so little competition because, “since the 1980s, two-thirds of all American industries have become more concentrated.”

This raises an obvious problem: Corporate concentration has been transpiring over decades. In 2019, U.S. industries were roughly as concentrated as they were in 2022. Yet in the former year, inflation sat near 2 percent, a low level by historical standards. In the latter year, by contrast, prices rose by 6.5 percent. So why did corporate concentration yield historically low inflation throughout the 2010s, only to suddenly produce exceptionally high inflation following the pandemic?

Reich acknowledges that the pandemic did increase corporations’ costs, raising the price that manufacturers must pay for energy, metals, and workers. But companies then used these genuinely higher costs “as excuses to increase their prices even higher” than necessary for offsetting those costs. Empowered by such excuses, and sheltered from competition by market concentration, avaricious companies powered inflation through price gouging.

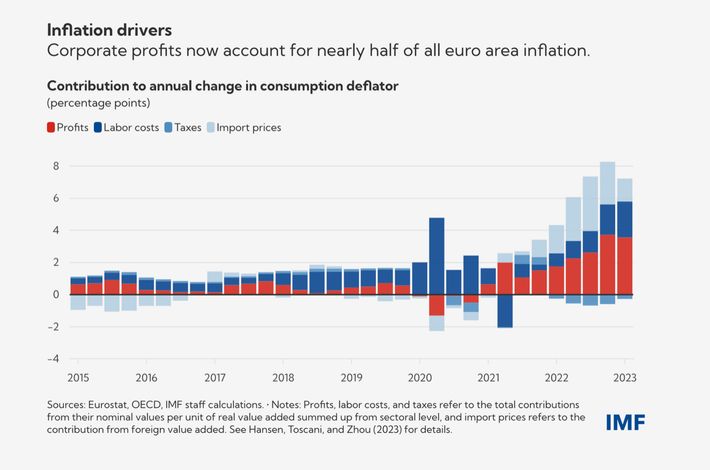

The primary evidence for this claim is the correlation between rising inflation following the pandemic and an increase in corporate profits. Between the fourth quarter of 2019 and the second quarter of 2021, pretax profit margins jumped from 15.6 to 17.9 percent. Proponents of the greedflation hypothesis will often support their argument with charts like this one from the IMF, which shows that profits “account” for far more of inflation in the euro area than labor costs do.

There are several problems with this argument.

First, it is unclear why corporations would feel compelled to wait for an “excuse” before seeking to maximize their profits. Ironically, Reich’s version of the greedflation thesis implies that corporate America put the public good above its own financial self-interest for years if not decades: During the 2010s, corporations could have charged much higher prices for their goods, as they were insulated from competition by concentration. But for years and years, they decided not to maximize their profits, since they lacked a compelling “excuse” for charging a financially optimal price.

This is an odd theory of corporate behavior. Generally speaking, companies do not feel compelled to provide an excuse for pursuing their mercenary interests. As Reich is keen to highlight in other contexts, U.S. firms have been perfectly happy to offshore jobs to low-wage areas, even in the absence of an economic crisis that would serve to rationalize such profit-maximizing endeavors. Pharmaceutical firms, meanwhile, routinely price-gouged on life-saving medicines, even when inflation was near historic lows.

A second problem with the crude version of the greedflation thesis is that the correlation between rising profits and rising prices does not actually tell us much about the cause of the latter.

Let’s stipulate that the conventional theory of post-COVID inflation is correct: Fiscal policy enabled demand for goods to outpace their supply, as the economy struggled to ramp up productive capacity following the pandemic recession. In that scenario, producers of goods would see the market value of their wares increase, since such goods would be scarce while consumer appetite for them would be abundant. This would make it possible for firms to secure a higher price for their goods, and therefore, to earn higher revenues. Those higher revenues would then either go to workers in the form of higher wages or owners in the form of higher profits, depending on the balance of power between labor and capital within the firm. But in either case, higher wages or higher profits would be an effect of the inflationary environment, not its cause.

Matt Bruenig helpfully illustrates this point with reference to inflation in the used-car market. Following the COVID recession, demand for personal vehicles outstripped their supply. This was largely a result of a shortage in semiconductors, a key input into modern automobiles. During the pandemic, consumers suddenly increased their spending on various electronics that use semiconductors. At the same time, COVID lockdowns in China (among other things) restricted the global economy’s capacity to produce chips. As a result, carmakers lacked the inputs to crank out autos at a normal pace.

Unable to secure new vehicles, consumers turned to the used-car market. The price of used cars accordingly skyrocketed. Between June 2020 and January 2022, the price of a used car in the United States jumped by nearly 60 percent, after previously holding steady or declining for 25 years.

Sellers of used cars did not see their costs increase; such sellers have virtually no costs since they’re selling an already completed product. As a result, the increase in prices in the used-car market went almost entirely into higher profits. In the phrasing of the IMF chart above, profits would “account for” nearly 100 percent of used-car inflation.

But that wouldn’t mean that profiteering by car owners “caused” that inflation in any meaningful sense. The used-car market did not grow suddenly more concentrated after the pandemic recession, nor did car owners suddenly become more greedy. In the aggregate, they have always sought to get the best price they could for their vehicles. That “best price” simply increased due to a mismatch between the demand for, and supply of, used vehicles.

Proponents of the greedflation thesis suggest that their analysis has recently been vindicated by reports from the Kansas City Federal Reserve and European Central Bank. But as Bruenig notes, these claims rely on misreadings. Both reports note that profits have contributed to inflation more than wages. But in doing so, they are merely (awkwardly) describing the distribution of inflation’s benefits, not its causes. When discussing actual causal mechanisms, the ECB suggests “demand outpacing supply in many sectors” as one critical factor. The Kansas City Fed, meanwhile, explicitly rejects “the simple explanation of ‘greedflation,’ understood as either an increase in monopoly power or firms using existing power to take advantage of high demand.”

Notably, as the economy’s productive capacity has recovered, and supply has grown less constrained, profit margins have fallen. In the first quarter of 2023, pretax profit margins were back down to pre-COVID levels, even as inflation persisted (albeit, at a decelerating pace).

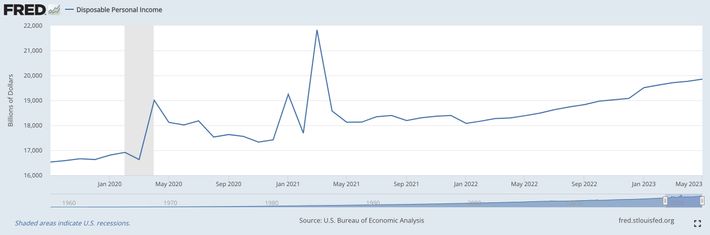

The final problem with the crude greedflation argument is that it simply ignores the very strong evidence behind the conventional account of the post-COVID inflation. Congress really did mount a historically aggressive response to the pandemic recession, providing households with so much financial aid, Americans’ disposable income actually increased during the economic downturn and has remained above 2019 levels ever since.

At the same time, fear of contagion led consumers to suddenly, collectively shift their spending away from in-person services and toward goods en masse, producing an abrupt surge in demand for goods.

Combine this with battered supply chains and a shrinking labor force (as many older Americans opted to retire all at once), and we would expect to see inflation, irrespective of corporations’ greed or market power.

In sum, the crude greedflation argument has no satisfying explanation for why prices rose when they did, relies overwhelmingly on a correlation that does not imply causation, ignores copious evidence that a mismatch between supply and demand has been the primary cause of inflation, and cannot account for the fact that price growth has persisted in 2023 even as corporate profit margins declined.

“Profit-driven inflation” is plausible but unproven (and doesn’t refute the relevance of fiscal policy).

In a paper titled, “Seller’s inflation, profits and conflict: why can large firms hike prices in an emergency,” the economists Isabella Weber and Evan Wasner provide a more compelling account of how corporations’ market power can exacerbate inflation in the context of a supply shock.

Their story (in highly simplified form) goes like this: In ordinary times, large firms are reluctant to raise prices. This is because, even in heavily concentrated sectors, a modicum of competition persists. Thus, if a company raises prices — but its competitors do not — it risks losing market share. And even if all relevant firms raise their prices simultaneously, they would still risk luring new entrants into their industry that could undercut them on price.

But this changes in the context of a supply shock. When bottlenecks in supply chains yield shortages of key inputs, the threat of competition ceases to restrain price gouging. This is because firms have less reason to fear that raising prices will cost them market share in such a context. After all, their competitors are scarcely able to produce enough goods to service their existing customer bases, let alone to expand them. And the threat that new competitors will enter the market all but vanishes, as firms that lack existing relationships with suppliers are unlikely to access the scarce materials necessary for production.

This dynamic is especially prevalent in highly concentrated industries. And it’s especially damaging in “upstream” sectors; which is to say, in industries that produce goods critical to the functioning of other businesses in the economy, such as chip-makers. When such upstream industries exploit bottlenecks to increase their profit margins through price gouging, they force downstream businesses to jack up prices too just to meet their costs. Eventually, this cascade of price hiking trickles down to workers, who respond to the erosion of their paychecks by seeking higher wages. Critically, however, workers in this model do not drive inflation through wage demands but merely respond to an inflationary dynamic that’s ultimately rooted in the pricing power of large, upstream firms.

Weber and Wasner support their account with reference to the ideas of myriad economic theorists and excerpts from the investor calls of select large firms in which corporate executives detail their pricing strategies.

Their theory of corporate behavior is plausible. And it does have implications for economic policy. If supply-chain bottlenecks can give critical upstream industries monopoly pricing power, which can then trigger an inflationary cascade that ripples downward through the economy, then preempting both shortages of key industrial inputs and profiteering in key sectors become vital policy goals.

Nevertheless, I doubt that even Weber and Wasner consider their paper a dispositive proof of their theory, rather than a starting point for a research program. They marshal significant logical and anecdotal evidence for their claims but not comprehensive empirical support. Most critically, their paper does not tell us what proportion of the post-COVID inflation is attributable to the specific pricing dynamic they spotlight, rather than to the increase in costs that they also acknowledge.

Indeed, even if we posit that Weber and Wasner’s account is entirely true, one could still read it as specifying one mechanism by which a mismatch between supply and demand exacerbates inflation, rather than as an alternative to macroeconomic explanations for inflation. After all, the dynamic they describe is ultimately contingent on demand conditions. In a context where supply-chain bottlenecks limit the supply of key inputs — but demand for goods simultaneously crashes — firms would not acquire the pricing power that Weber and Wasner describe. And that is no idle hypothetical. If Congress had responded to the COVID recession in the same way that it did to the 2009 recession — which is to say, if it had enacted a relief package far too small to offset the income that households lost to mass unemployment — then consumer demand would have been relatively tepid in 2021 and 2022, and inflation would have been lower.

That scenario would not be preferable to our current one. The cost of lower inflation in such a counterfactual would be much higher poverty and unemployment. But just because the fiscal response to the COVID recession is normatively desirable does not make it descriptively irrelevant to inflation.

What’s greedflation got to do with it?

I think that a lot of the rhetoric about greedflation reflects political anxieties rather than careful reasoning. Progressives wish to champion generous stimulus policies and tight labor markets. Acknowledging that both of those things can contribute to inflation by increasing aggregate demand would risk eroding public support for them. By contrast, casting inflation as a morality play, in which avaricious corporations single-handedly generate rising prices through greed, theoretically serves to direct mass discontent in a more beneficent direction.

In the Machiavellian realm of paid political messaging, this reasoning might be sound enough. Democratic politicians do not have the luxury of providing swing voters with a lengthy, nuanced defense of progressive macroeconomic priorities. Thus jeremiads against corporate greed may serve as an expedient shorthand for progressives’ broader economic argument.

But in the realm of elite policy debates — where people with influence occasionally read and think carefully about competing arguments — wedding the left’s prescriptions for inflation management to an incoherent and unsubstantiated analysis of the phenomenon’s causes seems unwise. Doing so mostly serves to both distract from, and unduly discredit, heterodox proposals for combating price growth.

After all, the validity of (virtually all) such proposals does not actually hinge on whether corporate profiteering caused inflation. Weber and Wasner argue that policymakers should facilitate the creation of buffer stock systems for critical inputs and industrial commodities, so as to render the economy less vulnerable to supply shocks. The case for this proposal is strengthened by their theory of “seller’s inflation.” But the case for buffer stocks does not actually require that theory. Building excess capacity of critical inputs to increase resiliency would be a good idea, even under the conventional account of the post-COVID inflation’s causes. And many analysts who reject Weber’s theory nevertheless endorse the creation of buffer stocks.

The same can be said of Weber’s call for imposing strategic price controls on critical commodities or goods as a last resort, particularly in contexts where a cartel or oligopoly of producers enjoy considerable pricing power. One can justify imposing price caps on natural gas and oil without stipulating that corporate profiteering was the primary cause of inflation, or that fiscal policy was largely irrelevant to it. Indeed, Noah Smith, a harsh critic of greedflation, endorses such price caps.

Similarly, one can make a case for windfall-profits taxes and anti-price-gouging measures without endorsing the greedflation hypothesis. In my own view, it isn’t necessarily all bad for producers of high-demand goods to earn high profits — if they reinvest those profits into expanded production. If the public’s need for vaccines or computer chips far outstrips their supply, then it would be good for the makers of such things to have more capital at their disposal. On the other hand, if such producers earn windfall profits, then disperse them to investors rather than reinvesting them, there is a case for public policy to change their incentives or redistribute their earnings.

Most critically, one does not need the greedflation thesis to defend robust stimulus policies or tight labor markets. The COVID pandemic did real damage to the economy, which needed to be paid for in one way or another. Had Congress appropriated substantially fewer relief funds to the unemployed and households, we would have paid for that damage through higher unemployment and a slower recovery. Instead, we have been paying for it through elevated prices. In theory, the federal government could have calibrated fiscal policy a bit more optimally. But it had to make decisions under conditions of uncertainty, and decided to err on the side of too swift a recovery in consumer demand. Given the immense costs of sustained periods of mass joblessness, this is wholly defensible.

Perhaps, the most productive function of the greedflation discourse is to emphasize that wage demands have not been the leading driver of inflation, as the distribution of heightened corporate revenues went primarily to capital in 2021 and 2022. Still, one does not need the greedflation narrative to argue that we shouldn’t seek to combat inflation by engineering higher unemployment.

The case for the Federal Reserve to spur a recession rests on the notion that only an increase in joblessness can avert a ruinous wage-price spiral. The logic of this idea goes like this: In a tight labor market, where spare workers are scarce, firms must raise wages in order to attract and retain staff. As their labor costs go up, such firms are then forced to raise prices. As prices go up, workers’ demand higher wages and, since unemployed workers are few, firms must acquiesce. This cycle produces accelerating inflation. Thus, the alternative to easing pressure on the labor market now through a modest recession is easing it later through a brutal one.

Yet one can stipulate that tight labor markets increase demand (and thus, facilitate inflation) while still rejecting this story. For one thing, it just doesn’t seem to check out empirically. Since last September, inflation has fallen substantially, even as unemployment has remained historically low.

One explanation for this development is that spare workers aren’t actually as scarce as the official unemployment rate would lead one to believe. As Adam Ozimek notes, the unemployment rate only counts jobless workers who are actively looking for a position, not those who aren’t on the job hunt but would nevertheless join the workforce for the right gig. But many workers fall into that latter category. As employment opportunities have improved, many Americans have gone straight from the economy’s sidelines into paid work. The prime-age labor-force participation rate has risen as a result.

But another explanation is that conventional economic theory greatly overestimates the contemporary economy’s vulnerability to wage-price spirals. In an America where only 6 percent of U.S. workers are unionized, and cost-of-living adjustments are a rare feature of union contracts, it’s not clear that workers can reliably force employers to raise wages in response to price increases. Indeed, for most of the past two years, wages have failed to keep pace with prices.

If we are not on the brink of a wage-price spiral, then the costs of engineering a recession are difficult to justify. Far better then for policymakers to try to combat inflation by encouraging increases in productivity and capacity. We can combat housing inflation by legalizing the construction of apartment buildings in areas where they’re currently prohibited. We can ease inflationary pressure in the healthcare sector by empowering nurse practitioners to provide a wider range of care, making it easier for immigrant doctors to come and practice in our country, and expanding medical school and residency slots.

Finally, you certainly don’t need the greedflation thesis to argue that corporate shareholders have it too good. Increasing the tax rate on capital gains in order to fund public goods is a worthwhile idea, no matter what caused inflation. And in the long term, the same is true of increasing labor’s share of national income through stronger collective bargaining rights.

Progressives don’t need to make dubious claims in order to advance their core economic goals. So they shouldn’t.