If the economy is doing so well — unemployment is low, inflation is falling, and the odds of a recession are dropping — why is President Biden’s approval rating so low? Liberals and moderates attribute the disconnect to such factors as the news-media environment, the unusually large shock of price spikes in 2021 and 2022, or various social maladies. (My colleague Eric Levitz posits that Biden’s age and demeanor are making Americans hesitate to credit the economy’s performance).

Conservatives smugly insist there is no disconnect at all. They point to alternative or obscure economic indicators, such as inflation in narrow segments of the economy, or simply insist that polling on the economy is ipso facto correct and liberals are out of touch for questioning the public’s perception.

I have a more simple explanation: There is just a time lag between the economy’s performance and the public’s ability to register it and credit the president.

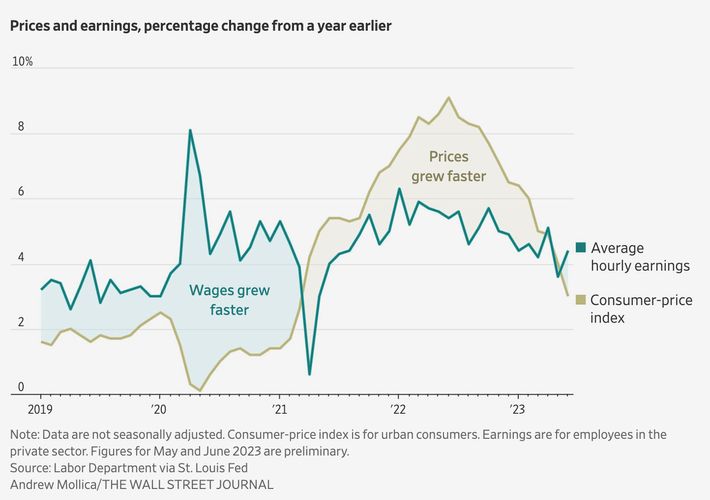

The best visual summary of the state of the economy I’ve seen comes from a recent article in the Wall Street Journal. Average hourly earnings are finally outpacing higher prices, but the former has only overtaken the latter very recently:

Now, as Eric pointed out, this measure is slightly pessimistic. The economy has disproportionately created jobs for blue-collar workers, who earn less money. This is a social good, and it has compressed inequality, but it has the side effect of decreasing the average hourly wage (since, say, waiters earn less money than lawyers).

Still, I think the chart broadly captures the fact that wages have been rising fast, but inflation has eaten up a lot of the gains (even if not, as the chart suggests, more than all of them) until recently.

The question is, how long does it take for a roaring economy to help an incumbent president? The relevant precedent probably takes us back quite some time. In 2020, the economy was in a weird state of suspension with government checks replacing normal wages but the economy hardly doing well. In 2012, when Barack Obama ran for a second term, the economy had recovered from the Great Recession but was nowhere close to full employment. The same thing was true in 2004 when George W. Bush ran for reelection. To find a clear case of an incumbent president running during economic prosperity, you have to go back to Bill Clinton in 1996.

In retrospect, Clinton’s reelection was a mortal certainty given the booming ’90s economy. At the time, however, this was far from clear. In July 1995 — about the same time in the cycle as now — the New York Times wrote a story attempting to measure whether the economy would help Clinton’s campaign or hurt it. Its verdict was equivocal.

“Even if the economy does bounce back in coming months, it is far from clear that there will be corresponding political gains for Mr. Clinton,” wrote David Sanger:

Certainly not all the news has been good, and anyone wanting to construct a pessimistic outline for the months ahead has plenty to work with. In May, personal income declined slightly, the first fall since January 1994. In June, a leading index of manufacturing purchases declined for the second consecutive month, after nearly two years of growth. Car sales plunged alarmingly in the spring, leaving the chief executives of the Big Three shaken. Mortgage applications are down, even though interest rates have dropped nearly two points in eight months. The savings rate continues to fall.

As the recovery continued, the perceived balance tipped slowly in Clinton’s favor. Even so, returning to the subject just over a year later, the Times still saw the economy as a politically mixed bag. “The deficit is down sharply and the economy, by most measures, is generally healthy,” it reported. “But typical American workers are in no better shape than they were four years ago. Adjusted for inflation, wages are almost exactly the same as in 1992 and about 6 percent below average wages of the late 1980’s.”

The Los Angeles Times, in a story leading with news of surging jobs, still noted in July 1996 that Republican presidential nominee Bob Dole “can take at least some comfort in evidence that voters have been less than euphoric about the state of the economy and divided over whether the president or his Republican challenger would do a better job in the head office.”

Republicans had insisted in 1993 that Clinton’s increase of the top tax rate would produce a recession, and they still maintained the economy was in terrible shape three years later. ”Clinton’s high-tax, big-Government policies have sucked life out of the economy, eaten up American workers’ pay and given money to the Government instead,” said Haley Barbour, the Republican Party chairman. “Clinton’s policies have created the middle-class squeeze.”

Dole decried what he called “the Clinton crunch,” his term for supposed economic stagnation. Here, from one presidential debate, is a sample of Dole’s rhetoric:

You may think the biggest employer in America is General Motors, but I’ve got news for you. It’s Manpower Services. Hiring people temporarily who have lost their jobs and they get to work for 30 days or 60 days. That’s a good economy? I don’t think so. They’re setting new records this year. We had the worst economy in a century. We had the slowest growth, about 2.5 percent … We had a 1.2 million bankruptcy, set a new record. Credit card debt has never been higher. I just told you about this manufacturing job loss which is going to increase. We need a good strong economic package, let the private sector creates the jobs and they can do it.

As the election neared and the economy kept roaring, this rhetoric started to sound less and less tethered to reality. Still, it remained plausible, and relatively in tune with public opinion, until the campaign’s closing stretches.

As we now understand, the economy in 1996 was in the midst of a historic surge that created growth up and down the income spectrum. Many Americans look back at that time as almost a golden age of peace and prosperity.

But the striking thing about the political effect of the recovery is how long it took to set in. The 1991 recession, which sunk George H.W. Bush’s reelection, was already over by the election. The first few years of the recovery were painfully slow. Even so, public discontent lingered long after good times returned.

This precedent has mixed news for Biden. The good news is that it’s not that voters refuse to credit his economic stewardship, but that it’s almost certainly too soon for them to do so. The bad news is that it’s not totally clear it will be soon enough even by next year. Which means Biden has to continue making the case for Bidenomics as persistently as he can.