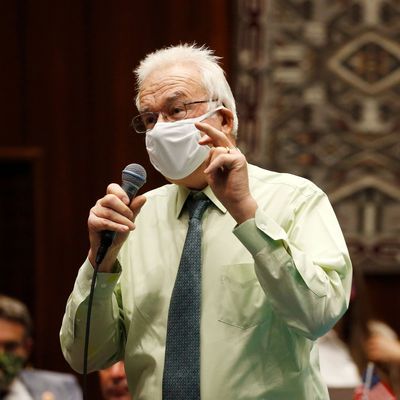

Representative John Kavanagh, a Republican legislator who chairs Arizona’s Government and Elections Committee and is shepherding through a bill to make voting more cumbersome and therefore rare, described his party’s motives with blundering candor.

“There’s a fundamental difference between Democrats and Republicans,” he told CNN. “Democrats value as many people as possible voting, and they’re willing to risk fraud. Republicans are more concerned about fraud, so we don’t mind putting security measures in that won’t let everybody vote — but everybody shouldn’t be voting … Not everybody wants to vote, and if somebody is uninterested in voting, that probably means that they’re totally uninformed on the issues. Quantity is important, but we have to look at the quality of votes, as well.”

Kavanagh’s error was to articulate in public beliefs that conservatives prefer to leave to members of their movement who aren’t accountable to the electorate. If I had to guess, his argument is something he’s picked up from reading conservative media, and he never realized his role as elected official makes it unwise to repeat — especially on-camera.

Donald Trump’s presidency, with its continuous demands to silence his opposition and efforts to undermine the election, highlighted his party’s anti-democratic character. But hostility to democracy is a long tradition on the right, including (perhaps especially) in its loftiest highbrow quarters.

Respectable conservative organs like National Review not only supported segregation and opposed civil rights, but also opposed laws to safeguard voting rights. The NR formula on voting rights has always combined several classic elements. First, there are usually some arch, snobbish gibes at right-wing populist demagogues, who are crass and beneath the dignity of the deserving elites at National Review. Second, the dismissal of rank bigotry is set against a “frank” concession that most Black people do not actually deserve the franchise because they are, like the poor whites who support the demagogues, too ignorant to exercise their vote wisely. And third, it declares states’ rights to be the paramount consideration, so that ultimately no federal solution can be imposed, however troubling the abuses of the state-level authorities.

In 1965, James J. Kilpatrick’s National Review cover story dismissed the need for a Voting Rights Act. Yes, Kilpatrick conceded, white Southerns had mistreated Black people. (“No reasonable man would deny that in times past, the South has sinned against the Negro; here and there, in times present, the abuse continues.”) However, the fact remained, “Over most of this century, the great bulk of Southern Negroes have been genuinely unqualified for the franchise. They emerged illiterate from slavery; they remained for generations, metaphorically, under the age of twenty-one.” And the principle of federalism meant Congress could not dictate voting procedures to the states, so, sadly, the Voting Rights Act “undertakes to remedy a perversion of the Constitution by perverting the Constitution.”

A 1966 column by Buckley began with some mockery of Alabama governor George Wallace. But Buckley proceeded to his main point. “For some reason it has been hailed as a triumph of democratic justice that so many Negroes succeeding in voting last week,” he sneered, mocking the absurdity of illiterate Black Alabamans being permitted to vote. Weighing the competing absurdities of the two “evils” — Wallace’s buffoonery, or Black people voting despite having been denied an education by their state — he concluded “the latter” was worse. (The text of these columns are not online. Joshua Tait, a University of North Carolina historian specializing in conservative thought, shared the quotes with me.)

After the 1960s, most mainstream conservatives abandoned their defense of de jure segregation in the South, and two decades later had to abandon their defense of the same system in South Africa. But the idea that voting rights ought to be restricted remains a staple of conservative thought to this day. The chilly reception National Review and other right-wing elites afforded Trump was in keeping with their traditional contempt for demagoguery. But the danger they identified in him was not that he threatened democracy, but seemed in their mind to embody it. “We must weed out ignorant Americans from the electorate,” insisted David Harsanyi in 2016. National Review’s Kevin Williamson, in a column last year headlined “On the Dangers of Democracy,” warned, “The rising authoritarianism of our time is not an aberration but the ordinary natural fulfillment of mass democracy when it has overflowed its constitutional restraints.”

Conservatives are hysterical in opposition to proposals in Congress to guarantee voting access and limit gerrymandering. National Review calls H.R. 1, the main House bill to promote election reform, “a partisan assault on American democracy.” But NR should be more honest in its criticism: Democracy is not what it wants at all, and never has been.