Sewer workers in 1910 had a nickname for the mold that grew in Lower East Side sewers. “Lace curtains,” they called it, because the stuff was white and draped prettily across the sewer arcs. At a time when the city was steeped in filth—children romped in the slime of horse troughs, industrial rendering plants rendered—the Lower East Side was exceptional for its grease deposits, and smelled persistently of shit. There are no lace curtains to be found a century later, as the price of an apartment on Orchard Street indicates. If there’s any scent at all in 2011, it’s the scent of discretionary income: of gluten-free doughnuts, premium jeggings, artisanal cigars.

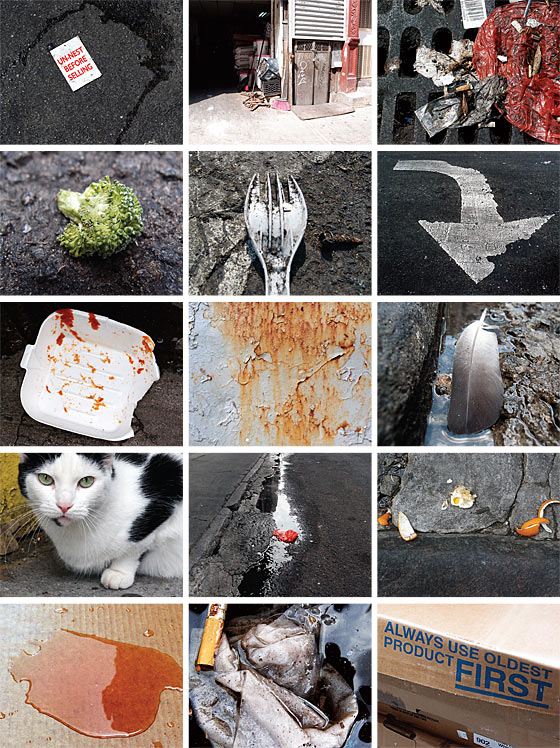

One particularly striking exception remains. It’s a mystery, the stretch of Broome Street between Allen and Eldridge—a quiet little block that smells like high meat and old squeegees. It gets bad in the spring and worse in the summer, when the smell of decay is overpowering. “Everyone around knows that block is the stinkiest block in all of Manhattan,” a resident named Kate told me. Elie Z. Perler, a neighbor who edits the website Bowery Boogie, agrees. “Not even the most disgusting subway smell compares,” he says. “I try not to eat while walking there, since I’d probably throw up.”

David Swanson, a former resident who has lived in several Third World cities, says he has never experienced anything like the “flushed-out catacomb” smell of the block, and it is true that the street’s stink has a menacing quality. To walk down Broome on an August afternoon is to spend a few minutes confronting the idea of dying, rotting, and smelling like Broome Street. The source of the smell is unknown.

Chandler Burr, the curator of the Department of Olfactory Art at the Museum of Arts and Design and former perfume critic for the New York Times, agreed to canvass the block with me on a recent damp morning in pursuit of clues. Starting on the western edge and moving east, the first thing Burr detected was food. “That’s a wok and hot oil,” he said, surveying the territory nose-first. “And a brown sauce. A generic Hunan sauce.”

We walked east. “Now cabbage,” Burr said. “Chinese cabbage.”

An elderly lady down the street pulled a cart in our direction, looking frail but moving fast. With her free hand, she pressed a folded paper towel across her nose.

“Holy shit, that’s urine,” said Burr. “That’s urine. Human urine. That’s like, you’ve got your face in the urinal.”

He stopped to inhale. The urine was presently replaced with the smell of cigarette smoke and Tide detergent, both wafting from a bodega. It was tough to localize the urine. Burr kept going until a current of the signature Broome odor whistled past.

“Whoa,” he said, stopping on a dime. “Cat urine. Wet dog. Live dog. It’s that,” he said, pointing to an open warehouse at 284 Broome Street. We vectored over to the threshold of the warehouse, which was open to stacks of boxed rice, paper towels, and cabbage. The odor didn’t seem to involve any of these things. It was ripe and outlandish in a way that made a person feel perverted.

“Unbelievable,” said Burr, shaking his head. “Absolutely unbelievable.”

A man sitting inside the warehouse waved at us.

“I can’t believe they let a person sit in there,” Burr murmured.

Could this curator of the Department of Olfactory Art identify the source of the smell?

Burr shook his head grimly. “I have absolutely no idea.”

The following week, I met Avery Gilbert, an expert in odor perception and the author of What the Nose Knows: The Science of Scent in Everyday Life, on Broome with a similar plan in mind. He directed my attention to a gutter with a sock floating in it and diagnosed standing water as the area’s first problem. “It’s a bacterial broth,” he said. “There’s a nice oily sheen to this one. Smells like rotten vegetables.” The air was a mesh of flies. At 284 Broome, the warehouse was doing a slow Saturday business, and as we approached the building, Gilbert replicated Burr’s body language. “Ay-yi-yi,” he said. “Wow. Oh, boy. Oh, boy.”

The smell was so bad he began to laugh.

“It’s like a litter box,” Gilbert said. “Cat urine. Cats.”

Cats!

So, I questioned, the smell is cats? Cats in large quantities?

But he wasn’t so sure. “It’s hard to determine without seeing,” he said. “So much depends on the context.” I nodded, grateful that at least Burr and Gilbert had succeeded in pinpointing 284 Broome as the source of the odor. Scanning the area for leads, I noticed a cellar stairway adjacent to the warehouse. It was slicked with graffiti, dust, and stickers reading CHICKEN WITH GIBLETS and CHICKEN WITHOUT GIBLETS. When I showed Gilbert the stickers, his eyes narrowed. A forklift beeped in the distance.

“You ever been around a chicken farm?” he asked.

I shook my head.

“The ammonia smell can bring tears to your eyes.”

We stood gazing at the cellar, our eyes watering.

But what about the cats? I said.

“The two smells are similar enough,” Gilbert said, breathing through his mouth. “Live poultry is my best guess.”

The Manhattan poultry trade sprang up in the late seventeenth century, when a cluster of markets opened shop along the southern tip of the island. By the nineteenth century, slaughterhouses had crawled uptown and were thriving along the Hudson River. Despite public concern about the stench, an ardent demand for meat kept the abattoirs in business. There were also reports of out-of-state dealers stuffing birds with sand, packing fowl in saltpeter, and rinsing slimy meat with chemical potions to give them a fresh appearance. Increases in regulation helped to cut down on health scares, but the city’s poultry trade remained uncommonly volatile. A trade war erupted in 1914, when one of the city’s most prominent poultry dealers was murdered by business rivals after being accused of fixing wholesale prices. The lengthy trial that ensued implicated a wide-ranging gang of chicken handlers—one of whom admitted to six assassination attempts on the victim, including once with a poisoned dagger—as well as a chicken inspector known as Kid Griffo.

By the sixties, most of Manhattan’s slaughterhouses had moved elsewhere, and of the 80 live-bird markets currently holding permits in the New York City area, only four are in Manhattan: two in Inwood, one in East Harlem, one in Morningside Heights. But expand your parameters into the outer boroughs and live-poultry markets become much easier to find. There are 28 licensed markets (and untold illegal ones) in Brooklyn alone. The customer base is divided unevenly between those who buy live animals out of habit and those who do so out of principle or curiosity. Carlo Formisano, the manager of La Pera Poultry in Brooklyn, estimates that 65 percent of his customers are immigrants, and the rest are “people coming in from what I call Yuppieland,” who began to trickle in four or five years ago. Keeping one’s own chickens is legal in New York City—and increasingly popular. Owen Taylor, the city farms program manager of Just Food, says his Meetup group for city chicken keepers has almost 500 members, a couple of whom raise the birds for meat. “That way they know what the chickens are being fed and how they’re treated, and they’re directly involved with the slaughtering process.”

The problem with poultry slaughterhouses, however, is that they are lousy places to work up an appetite for chicken. As the Times recently noted, a Greenpoint slaughterhouse abutting new condos has been defaced with graffiti that reads THIS PLACE STINKS. If the smell issuing from 284 Broome does in fact derive from chickens, it may be less a remnant of the city’s history than a harbinger of its future. Poultry raised and slaughtered within subway range could well be where a locavore’s bluff is called.

But could the tenant of 284 Broome, Yu & Qiang Trading Inc., be keeping live chickens even without a poultry-market permit? The State Department of Agriculture and Markets told me it was classified as a food warehouse, and according to the Department of Environment Protection, it passed its last inspection with no violations.

When I returned to the warehouse for the eighth time, it was empty except for a worker toodling around on a bike. The air was 84 degrees and smelled very bad. I asked the worker if his employer sold chickens.

“Chickens, yes,” he said, biking closer.

Live chickens?

“No. Fresh.”

Ducks too? I asked.

The worker pedaled away without responding. I called the number listed on the building’s awning and was transferred to an English speaker. “No live poultry,” said the voice when I asked.

Is it fresh? I pressed.

“It’s frozen.”

There was a pause.

“I think,” he added, and hung up.

The fact-finding mission was not over. Concerned about the fuss I’d kicked up around 284 Broome, the Agriculture Department conducted an unannounced inspection last week. What they found, according to spokesperson Jessica Ziehm, was a big nothing: no live chickens and no evidence of live chickens. No live ducks, turkeys, pigeons, or any other kind of edible, respirating creature, either. The bad smell appeared to come from “stacked boxes of processed poultry sitting in the warmth.” Gross, but not illegal. Yu & Qiang Trading Inc. continues to enjoy a lively summer season, smell be damned. Chicken costs 93 cents a pound.