Perhaps you’re reading this in the back of an Uber (hopefully not in the driver’s seat), while you wait for scores of pedestrians to waddle across the street and get out of the way of your left turn. Or you’re one of those slow-moving pedestrians, glancing up from your screen long enough to register the fleet of mammoth Escalades snorting in impatience while you cross. Or you’re sitting on a bus that keeps its doors open while a passenger maneuvers her walker over the mound of snow that’s been plowed up against the curb. Maybe you’ve saved these words for later because right now you’re busy threading your bike through the mesh of foot and car traffic and dodging a delivery truck parked in the green-painted lane that has theoretically been set aside for your use. All of us — drivers, cyclists, pedestrians, subway riders, cops, and delivery workers — are locked in a matrix of mutual dependency. Many of us pass frequently from one category to another: Anyone who steps out of a car instantly becomes a pedestrian. When one group can’t move easily and safely around the streets, it usually means the rest of us can’t either.

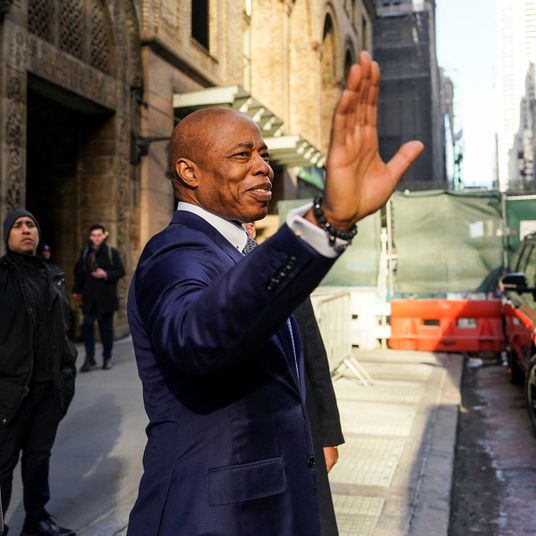

It’s because of this complex, interlocking system that a 104-page transportation plan released by New York’s city council speaker — usually the kind of dry, chart-filled document that generates a frenzy of yawns — is actually exciting. Speaker Corey Johnson has made himself suddenly indispensable by swooping in on one issue that affects virtually everyone: how we move around. Attention has focused on his proposal that the city take control of its own transit system. It’s a rare politician who’s eager to take responsibility for the subway’s failings, but potentially even more transformative is Johnson’s ambition to overhaul the streets. He begins from a deceptively simple principle: New Yorkers should be able to get around without sacrificing their dignity, their sanity, or their health.

Johnson’s report begins from the premise that the status quo is broken; each topic opens with the heading “What’s Not Working.” That’s not an easy sell. Everyone loves to grumble, but most people cling to the status quo anyway, no matter how menacing it is for others. And it is menacing. I walk wherever I can but all it took was a minor injury to make me feel, literally in my bones, how unforgiving this city is of physical frailty. A broken (or nonexistent) subway elevator, a blocked storm drain, an unshoveled sidewalk — each of these contretemps can transform an ordinary errand into a harrowing trek. New York should be a global leader in mobility of every kind; instead, it’s bogged down in good intentions.

We know how to do better. Fixing the subway is a colossal and expensive task, but making the streets more livable requires no advanced technology or multibillion-dollar deals — only paint and asphalt, plus consistent enforcement and political stick-to-itiveness. Protected bike paths and dedicated bus lanes work. Banning cars leads to less pollution and fewer deaths. It’s not mysterious.

What’s innovative about Johnson’s approach is that it places all these basic tools at the service of a “comprehensive transportation vision.” True, that phrase that can read like politico-speak for doing nothing, while promising to do more — eventually. And yes, Johnson has taken some heat for opposing a temporary busway on 14th Street that was designed to alleviate the misery of the now-averted L train shutdown. Transit advocates in this city fight hard for incremental steps, and they hate to see one scrapped without a fight. But you can keep taking baby steps and stay pretty much in the same place forever.

New York is a rusted machine, clotted and creaky, and the only way we can all move through it more smoothly is if we overhaul the whole contraption. “Without concrete, long-term goals for redesigning streets and intersections, it is difficult if not impossible to objectively measure the City’s progress on transforming our streetscapes for improved safety,” Johnson writes. He points to the surgical street designs that the Department of Transportation carries out in crash-prone spots or to help pedestrians with disabilities. These interventions are great, and the report calculates that the DOT is on track to finish all of New York’s 47,000 intersections right around, oh, 2189. (There should be fewer intersections to worry about by then, since many could be underwater.) Sick of waiting, some neighborhoods are coming up with comprehensive visions of their own. The Financial District Neighborhood Association commissioned a proposal meant to “reclaim its streets from cars, garbage, and construction debris” — an ambitious DIY urbanism effort that beleaguered residents of less affluent areas could never afford.

Johnson wants to do it all, urgently: overhaul the subway, fix intersections, stitch the city together with protected bike paths, give buses their own inviolable lanes and priority at street lights, redesign streets, turn over large chunks of the city to pedestrians, halve car ownership, rethink deliveries, and maybe even tear down part of the BQE. If all that seems wildly out of step with reality, consider how quickly and thoroughly New York transformed itself over a century ago to accommodate the horseless wagon. The first crash on city streets took place in 1896. In a little over a decade, the father of traffic laws, William Phelps Eno, had invented the rotary circle, the stop sign, and the one-way street. In the ensuing decades, workers ripped up sidewalks to make way for additional traffic lanes, and belted the boroughs in highways. Starting in 1950, drivers could park their cars on city streets overnight, and sanitation crews cleaned around them. No city in the world could afford to defy the automobile without turning itself into a backwater, and New York was a leader in the automotive revolution.

Now it’s past time to undo that obsolete form of progress, and this time, New York is falling behind. Oslo has banned cars completely from much of its center, and reclaimed hundreds of parking spots. Far from crippling the local economy, as business owners feared, the pedestrianized areas are attracting more foot traffic. Compared to plans in Paris, London, and Madrid, “our efforts to pedestrianize streets … have been piecemeal and timid,” Johnson writes. “Simply put, the City remains mired in a car culture.” He’s in a hurry to haul us out.