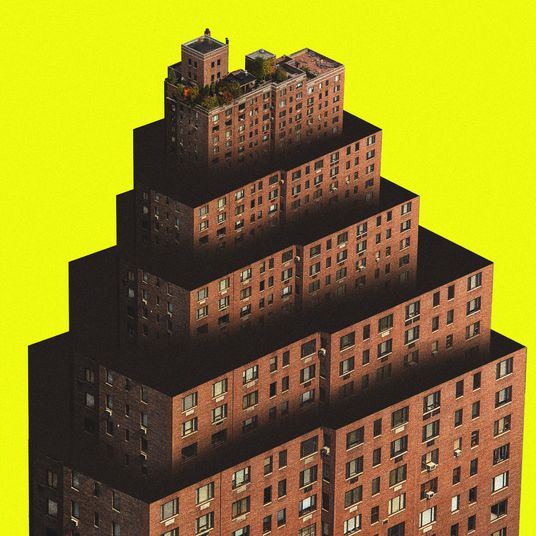

During Manhattan’s first couple of centuries, water was always a short stroll away. Tall masts swayed at the end of the block, the newest houses sitting on moist soil that had only just been wrested from marshland. Over the years, the island was fattened, its edges pushed out by filling the shallows with dead horses, broken carts, household refuse, and rubble from ceaseless street-grading projects. Much of this extra land sat just inches above high tide; waves slopped over piers and quays and hurricanes barreled through every once in a while, but each time the city dried off and rebuilt. Now the waters are coming back to stay.

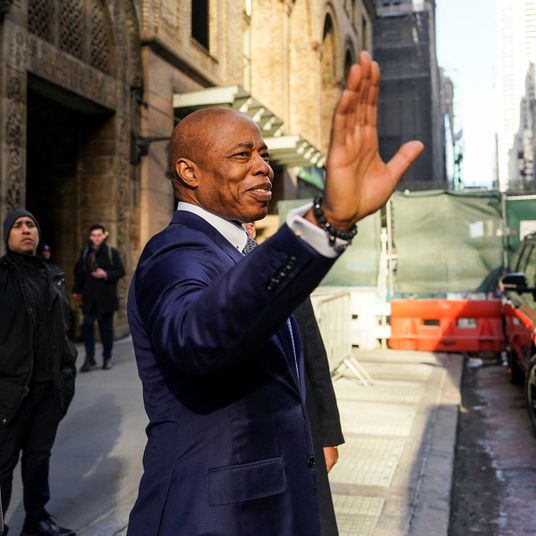

Superstorm Sandy gave New Yorkers a preview of the future in 2012, yet it’s not just mammoth waves that will dampen the city’s future but the slow-moving, inexorable advance of the seas. In the coming decades, the tides will find New Amsterdam’s original coastline, lapping the corner of Wall Street and Pearl Street, at times even rushing up to Bowling Green. Left to its own devices, the Financial District will look like a high-rise Venice, its spires in the clouds and its feet in the brine. Which is why Mayor Bill De Blasio has produced a new plan to keep lower Manhattan dry. It’s a combination of makeshift barriers and megaprojects: hilly waterfront parks, higher esplanades, floodwalls that can be deployed when a storm is bearing down, and even a new chunk of the city slung out into the East River. “It will be one of the most complex environmental and engineering challenges our city has ever undertaken and it will, literally, alter the shape of the island of Manhattan,” the mayor wrote.

If that portentous tone sounds familiar, it may be because in 2013, then mayor Michael Bloomberg announced a similarly sweeping and urgent, $20 billion proposal: “we refused to pass the responsibility for creating a plan onto the next administration,” he declared. Well, here we are, six and a half years after Sandy, just barely getting started. True, the city has moved a few inches off square one. The Bjarke Ingels Group, one of the participants in the new study, has redesigned the East Side waterfront, from East 25th Street down to Montgomery Street on the Lower East Side, a project partly funded by a $338 million federal grant left over from the Obama Administration. That segment, plus others near the Manhattan Bridge, Battery Park, and Battery Park City, are slogging through the design and approvals process, and could conceivably begin construction within the next two years. By the time the last megastorm’s tenth anniversary rolls around, we might see a few scattered measures to guard against the next.

Jainey Bavishi, director of the Mayor’s Office of Recovery and Resiliency, points out that the new plan comes equipped with the first comprehensive analysis of how flooding would affect which streets and buildings, plus a more realistic sense of what can be achieved, and when. “The science has evolved rapidly, and we have a lot more certainty of what things are going to look like,” adds James Patchett, president of the city’s Economic Development Corporation. Maybe so, but the proposal is short on details, which will have to be worked out block by block, in hundreds of community meetings. For now, the document reads as though it had been conceived to justify De Blasio’s vaguely comical presidential ambitions, a table-thumping plea for national attention.

The most troubling section is the one that finds an unpatchable hole in the city’s coastal defenses: the mile-long stretch from the Brooklyn Bridge to Battery Park, including the Financial District and South Street Seaport. Here, buildings, bridge piers, utilities, tunnels, and the FDR Drive are so tightly jammed and so close to the water’s edge, that there is nowhere to slip in a berm or a flood wall. Leave it as is, and 20 percent of the neighborhood will eventually flood every day. De Blasio’s planners insist that to keep water from invading the land, land must invade the water. The only option, they say, is to erect a barrier in the East River, somewhere between 50 feet and two city blocks out from the current shoreline. Protecting the multibillion-dollar investment that is lower Manhattan requires another multibillion investment, and the sheer quantities of stone, steel, people, and money packed into that narrow spit justifies the expense and the ecological disruption. A couple of decades from now, you might walk to the end of Wall Street, and instead of ducking beneath the FDR and getting on the ferry, you could just keep walking uphill.

The prospect of creating new acreage within shouting distance of Wall Street could quickly turn an environmental tool into a real estate boondoggle, raising the specter of an offshore Hudson Yards. Patchett insists that the city would rather create a park than a neighborhood, but that depends on whether the federal government comes back around to seeing climate protection as a national security issue. “It’s everyone’s preference not to do development there,” Patchett says. “But we may need some development to finance it.” In other words, if the government doesn’t step up, private investors will, so long as we let them build something they can sell.

The modern desire to colonize the river predates anxiety about climate change. The 1966 Lower Manhattan Plan proposed continuing the 300-year-old task of pushing the island’s edges out in all directions. Part of that vision evolved into Battery Park City, a neighborhood elevated just high enough to survive Sandy unscathed. Bloomberg administration’s 2013 plan envisioned a new high-rise Seaport City slung into the East River. A few years later, the engineering firm AECOM—the same company that carried out the analysis for the De Blasio report—unveiled a wildly ambitious (and quickly shelved) plan to build Red Hook up and out, turning it into Brooklyn’s Battery Park City.

To some experts, though, walling New York off from the water makes about as much sense as air-conditioning Central Park. A few believe that coastal cities are doomed in the long run, anyway, and that the next century’s political, financial, and cultural capital will be in some safe inland spot with plenty of fresh water like … Cleveland. (If that sounds far-fetched, take a look at the Financial Times’ mesmerizingly visual reminder that today’s great city can be tomorrow’s backwater, and vice versa.) Optimists remain hopeful that coastal cities can adapt to an altered climate, just as they have to mass immigration, deindustrialization, economic upheavals, and war. But adapting doesn’t mean an impermeable barricade. Amsterdam, Copenhagen, and Venice got used to water coursing through their centers. New York forgot that skill long ago—Broad Street was once a canal, and so was Canal Street—so perhaps it could relearn it.

Sea level rise is only one of many threats that climate change will bring, and battling it can make the city vulnerable in other ways. Raise the city and wall it in, and you might find that flooding from torrential rainstorms has nowhere to go. An aged drainage system regularly leaves Riverside Park (which is partly built on a platform above railroad tracks) a semi-permanent swamp. The danger of spending fortunes on the wrong defenses is not confined to coastal cities. Last week’s catastrophic flooding in the Midwest revived an old debate over whether the matrix of levees crisscrossing the plains can keep up with intensifying weather. “There are two types of levees,” the geologist Nicholas Pinter told the Washington Post. “Those that have failed and those that will fail.”

New York has been adding to its real estate for hundreds of years, so another round of expansion seems an oddly archaic way of tackling a new problem, says landscape architect (and Macarthur fellow) Kate Orff. “If our goal is really to adapt to projected conditions, and not just preserve the status quo, I would focus on critical infrastructure, like hospitals, power generators, and transportation, rather than on a big comprehensive plan that encircles all of lower Manhattan, ” she says. The problem with one big fix is that it’s binary. If you don’t get it exactly right—if, say, a seawall proves to be too low for the job, or too expensive to complete—then you get it very, very wrong. “We know sea levels are rising,” Orff says, “but we have to ride a fine line between being prepared and not making huge mistakes that we cannot unmake.”