On impeachment, Republicans no longer know what to (officially) disbelieve.

Virtually all GOP lawmakers insist that the answer to the inquiry’s fundamental question is “no.” But the party can’t agree about what that fundamental question is. To Donald Trump and his closest House allies, the impeachment fight remains a dispute over whether the president offered the Ukrainian government a “quid pro quo” — which is to say, whether he bartered congressionally ordered military aid for an investigation into Joe Biden. But denying that Trump did precisely this now requires accusing current and former administration officials, including a decorated Iraq War veteran, of perjury, while also ignoring the various times the White House lost the plot and copped to its illicit diplomacy. Thus, many Senate Republicans want to take the battle to new terrain. For them, the key question is not whether Trump did what’s been alleged, but rather, whether his alleged actions merit removal from office.

Both frames are mere pretenses. Ted Cruz does not believe, as a matter of principle, that presidents shouldn’t be impeached for bribing foreign governments into investigating their domestic rivals any more than Donald Trump believes, as a matter of fact, that he never did any such thing. The GOP’s hypocrisy on questions of congressional procedure is unimpeachable. The party is not merely ideologically indifferent to corruption in foreign countries, but ideologically committed to abetting such corruption.

And yet, none of this (necessarily) means that the GOP’s defenses of Trump are unprincipled, only that its true principles remain unspoken. For Republicans, the question at the heart of both “Ukrainegate” and the impeachment inquiry is not really about what the president did, or what presidents can and cannot be removed from office for doing. Rather, it is about whether there is any distinction between Donald Trump’s political interests and America’s national ones.

To many conservatives, Democrats (and/or popular democracy) are a greater threat to America than Vladimir Putin.

The Democrats have taken pains to frame their impeachment inquiry as a defense of national interests that transcend party and ideology. And in the post–9/11 U.S., “national security” is the last redoubt of such transpartisan purpose. So, when seven swing-district Democrats came out for an investigation in the Washington Post, they put their personal service to the security state front and center, writing, “Everything we do harks back to our oaths to defend the country. These new allegations are a threat to all we have sworn to protect.” The inquiry’s star witnesses have struck similar notes. Lieutenant Colonel Alexander Vindman, in his opening statement to Congress, declared, “I am a patriot, and it is my sacred duty and honor to advance and defend our country, irrespective of party or politics.”

In this framing, the victims of Trump’s shadow diplomacy were not Joe and Hunter Biden, but America’s security, democracy, and constitutional order: By withholding aid without fiscal justification, the administration unlawfully defied the will of Congress. By unlawfully denying military assistance to a NATO-aligned ally under attack, Trump jeopardized America’s national security. And by using his official powers to generate legal and political problems for his domestic opposition, the president violated a norm that is essential to the preservation of free and fair elections in the United States.

In public, Republicans will declare these assertions untrue. But from the perspective of their party’s core activists and donors, they may be simply irrelevant. At a Trump rally in Ohio last July, two of the president’s supporters wore T-shirts that read, “I’d rather be a Russian than a Democrat.” The implication of this sentiment — that conservatives should have more contempt for the GOP’s domestic adversaries than for America’s geopolitical ones — was hard to miss. It was also rather easy to understand. Two decades after the Cold War’s end, in a moment of peak partisan polarization, why should an ideologically committed conservative fear Russia’s occupation of Ukraine more than a Democrat’s occupation of the Oval Office? Put differently, why should a person who believes abortion is genocide care more about constraining Putin’s influence over eastern Europe than the pro-choice movement’s influence over the judiciary? America is simply too secure on the world stage — and divided on the domestic one — for appeals to national solidarity in the face of a foreign menace to pack much punch.

Appeals to a bipartisan interest in defending democracy and the rule of law are a bit more potent. But for the GOP’s core interest groups, it is not at all clear that conservatives have an interest in preserving democratic or constitutional norms at the expense of short-term power (the Democratic coalition’s interest in preserving such norms is much clearer, for reasons outlined below). The party’s plutocratic donor base has long recognized a tension between its vision of good government and popular democracy. And that tension has grown more conspicuous since the 2008 crisis, as millennials have drifted toward socialism, and the GOP toward an ersatz version of producerist populism. Charles Koch can read a poll. He knows the Trump tax cuts weren’t passed by popular demand. From his wing of the party’s perspective, it’s not clear how protecting norms that enable free and fair elections will keep America off the road to serfdom (a.k.a. social democracy). But it’s quite clear how impeaching an incumbent Republican president with high in-party approval could demoralize the GOP base, and ensure a Democrat’s election in 2020. And it’s also readily apparent that, given another four years, Trump could consolidate conservative control of the courts for a generation, thereby insulating conservative economic orthodoxy against the threat of democratic rebuke.

The Christian right, meanwhile, has forfeited all dreams of a moral majority. They may expect to be on the right side of the eschaton. But they recognize they’re going to be on “the wrong side of history” — or at least, the history of a democratic United States. With the American public’s social liberalism steadily rising, and its rates of church attendance in decline, Trump’s Evangelical supporters have no unambiguous interest in combating the subversion of democratic elections; if the will of the American people is irreconcilable with that of God, than their movement has no investment in seeing the former’s will be done. But they share their plutocratic co-partisans’ interest in securing a seven to two conservative majority on the Supreme Court.

Finally, for the GOP’s nativist contingent, “the ceaseless importation of Third World foreigners with no tradition of, taste for, or experience in liberty means that the electorate grows more left, more Democratic, less Republican, less republican, and less traditionally American with every cycle.” Trump’s best efforts have been insufficient to significantly slow the diversification of the U.S. population. Republican efforts to undermine democracy — through various forms of targeted voter suppression and dilution — have been far more effective in neutralizing the (supposed) demographic threat.

In other words: The conservative movement increasingly understands itself as a minoritarian project locked in a rearguard struggle against an ascendent “socialist” left. The rhetoric of the party’s leading politicians and commentators routinely affirms this worldview, casting the stakes of partisan conflict in existential terms. The president has said that Democrats plan to establish “open borders,” and “infest” the country with illegal immigrants, because “they view them as potential voters!” He’s insinuated that the opposition party orchestrated an “invasion” of the U.S. by Central American migrants in a bid to steal the midterm elections with illegal votes. Fox News host Tucker Carlson has put the point more bluntly: Democrats are “plotting a coup” — one that involves winning power in 2020, and then immediately enfranchising illegal immigrants en masse as a means of permanently disempowering real Americans.

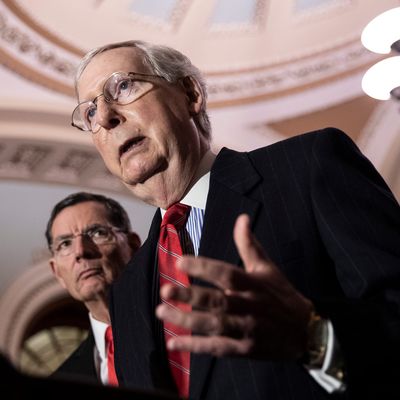

“Normal” Republicans are scarcely less hysterical. Mitch McConnell has said that Democrats are trying to foment a “socialist” takeover of the United States. Nancy Pelosi’s supposed “democracy reforms” would actually “make it harder for private citizens to exercise their right to political speech,” and thus, easier for Democrats to “seize money and power from American families and communities and pile it up in their own hands here in Washington, D.C.” House Minority Leader Kevin McCarthy, meanwhile, has accused California’s Democratic Party of stealing multiple 2018 House races through voter fraud. Figures like McConnell and McCarthy may not actually believe these things (Mitch surely knows that Pelosi is no Leninist). But many of their core constituents — and at least some of their congressional colleagues — do.

For much of the Cold War, bipartisan consensus held that it was in America’s national interest to topple any regime that (in our estimation) practiced a proto-authoritarian form of socialism — even if that regime had been democratically elected. If the Democrats are a socialist party hellbent on eradicating economic and religious liberty, and plan to use mass immigration and voter fraud to secure permanent control of government — as the GOP leadership routinely suggests — then Trump’s “quid pro quo” was ostensibly a defense of national security, not a subversion of it. If Ronald Reagan was justified in arming death squads to save other countries from socialist rule, surely Trump is justified in merely engineering an investigation into Joe Biden to save our own country from that fate.

As for Trump’s flouting of the separation of powers — his administration’s refusal to comply with subpoenas, and unlawful withholding of congressional appropriations — haven’t presidents from both parties skirted the letter of the law in the course of prosecuting the war on terrorism? Sometimes, you have to bend a constitutional order to prevent them from breaking it.

Democracy isn’t for everyone.

Liberals and Never Trump conservatives regularly castigate congressional Republicans for their cowardice. And certainly, some percentage of GOP politicians are abetting Trump’s malfeasance for craven, careerist reasons. But it’s the ones who are doing so out of moral conviction who should truly concern us. Understanding pro-Trump conservatives as a pack of spineless opportunists putting short-term political expediency above their highest ideals is almost certainly too optimistic. In a hyperpolarized political system — and in the face of demographic and ideological headwinds — many conservatives simply see little reason to value the maintenance of democratic norms above the preservation of their movement’s power.

And their reasoning is intelligible. Few people sincerely value liberal democracy as an end in itself. Reverence for that form of government is typically rooted in the conviction that it will produce justice more reliably than any alternative. For most of our history, the American right has viewed that premise with skepticism, arguing for restrictions to the franchise — and circumscription of individual rights — on the grounds that making such liberties universal would jeopardize higher goods. In our republic’s earliest years, reactionaries railed against voting rights for unpropertied white men, and rights of any kind for enslaved African-Americans. The terms of debate shifted as “the moral arc of history” bent. But it was only six decades ago that the leading light of the modern conservative movement asked himself “whether the White community in the South is entitled to take such measures as are necessary to prevail, politically and culturally, in areas in which it does not predominate numerically?” and concluded, “The sobering answer is ‘Yes’ — the White community is so entitled because, for the time being, it is the advanced race.” And it was only 17 years ago that the current Senate majority leader argued against the enfranchisement of former felons on the grounds that “voting is a privilege.”

American conservatives have opposed liberal democracy — universally applied — longer than they’ve endorsed it. And in recent years, Republicans have grown increasingly skeptical that popular democracy is compatible with their conceptions of liberty and justice. On the state level, the party has already taken a variety of measures to safeguard the latter by abridging the former.

Both sides don’t do it.

The American left has its own tensions with democracy and constitutionalism. Many of the progressive movement’s causes put it on the wrong side of majoritarian opinion. Popular sovereignty in our majority-white country has long frustrated the left’s aspirations for racial justice. Meanwhile, our constitutional system’s myriad counter-majoritarian institutions, and minefield of legislative veto points, have become insuperable obstacles to radical reform on matters as urgent as the climate crisis. If progressives believed that they could secure reparations and a global Green New Deal by abetting a Democratic president’s lawless assaults on the constitutional order and free and fair elections, it’s conceivable that they (we) would do so.

But that hypothetical is absurd; because the left’s predicament is not analogous to the right’s. Progressives represent minoritarian interests who are disempowered in the economy and civil society (the poor, nonwhite, and undocumented). The conservative movement’s core interest groups, by contrast, are economically and socially powerful minorities. This reality has long made the preservation (and/or realization) of democracy — and universally applicable laws and civil liberties — the left’s best bet for achieving its vision of a just society. We may not have the numbers on our side just yet, but — unlike the right — we’ll never have the guns or money. Meanwhile, auspicious demographic and ideological trends have bolstered progressives’ democratic faith. True, that faith has also rendered the left more critical of anti-democratic aspects of our constitutional order. But the progressive vision for restructuring that order involves winning control of a Democratic Party that is presently dominated by procedurally conservative institutionalists, winning free and fair elections, and then passing laws.

The right’s situation is more ambiguous. It isn’t hard to make an argument for why it is in conservatives’ best interests to safeguard liberal democratic norms: The structural biases of U.S. electoral institutions guarantee the party of white rural America a hefty share of power, no matter how anti-majoritarian its worldview becomes. And as conservative Christians grow more socially marginalized, they may come to appreciate the virtues of liberal pluralism.

On the other hand, the right has paid little price for its escalating assaults on democracy and lawfulness. Targeted voter suppression, dilution, and disenfranchisement has secured the Republican Party’s grip on power in states across the country, and helped to facilitate Donald Trump’s election. Ruthless apologetics for the president’s corruption, meanwhile, have helped the movement to secure tax cuts for the Koch Network, and Supreme Court justices for the pews. And although the party’s excesses may have cost it the House, available polling still gives the GOP a solid chance of keeping the presidency and Senate in 2020 (and therefore, the judiciary for decades). What’s more, any course of action that increases public cynicism about politics and government serves to devolve authority to the private sector, which the movement’s patrons rule.

If the GOP were a party of unprincipled opportunists, it would have little quarrel with democracy, or need for Donald Trump. Republicans could be a party of Charlie Bakers, winning free elections through ruthless pandering to the preferences and prejudices of the American middle class. The right is not slouching toward autocracy out of cynicism. It is conservatives’ devotion to their highest ideals that makes them a threat to our republic’s.