After trying for days to get a vaccination appointment, Katie Urban snagged one at 10 a.m. on Wednesday — for 11:20 a.m. that same morning. “I called my boss and said, ‘I gotta go,’” she said, and took off for an hour-long drive to the Bronx from the Mapleton section of Brooklyn where she lives. “It felt like winning the lottery.”

With little time to spare, she arrived minutes before her appointment only to find hundreds of people waiting in front of her, forming a line that snaked around the perimeter of a courtyard in Co-op City, where the city’s Department of Health set up a vaccination site. The sight alarmed Urban and many others. I too had come to be vaccinated, swallowing my anxiety about missing my slot to obey the guidance not to arrive more than ten minutes early.

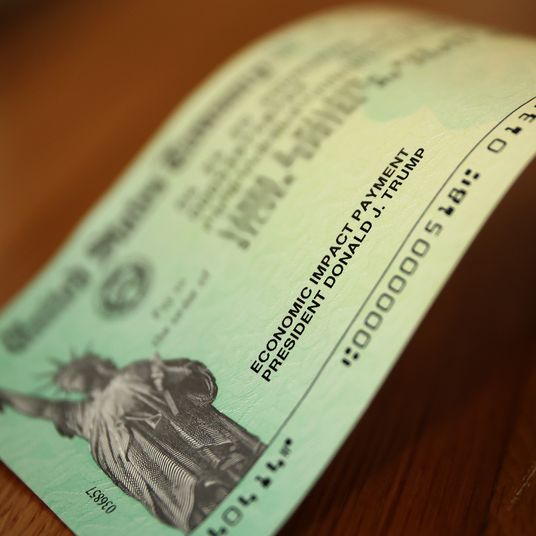

The reason for the long line was due to what volunteers said was a “glitch”: The department’s registration website had opened a staggering 40,000 appointments, which a health department spokesperson later said led to 600 additional people being overbooked for the site on Wednesday — a sign of how fierce the competition for slots has been after Governor Andrew Cuomo announced on Monday that all New Yorkers over 30 were eligible for vaccination. There were 1,500 shots of Johnson & Johnson’s single-dose vaccine available there on Wednesday.

People working at the site apparently had no idea the deluge was coming. Signs hastily fashioned out of notebook paper taped to walls pointed to where the line began with fat black arrows. That left the crowd to control itself, with people in masks pantomiming dramatically that the line started way over there. One man jumped in front of another man half his age, perhaps puzzled, as the rest of us were, about what was going on. The younger man pointed across the courtyard and the older man shrugged with indifference. Then the younger man wound up like he was going to throw a punch, which sent the older man skittering away, orange handcart in tow. A security guard named Mike described the day so far as “a little chaotic.”

We were warned the wait could last up to three hours, or we could stick around and get rescheduled for Thursday or Friday. I saw no one take up that offer — waiting three more hours was minor compared to waiting the last year for deliverance from the virus.

Ten minutes later, another volunteer, whose gray hair conveyed some authority, appeared. “That is the boss,” he motioned behind him to someone even higher up. “We’re not taking more people.” He said the city had denied the site more vaccines to cover today’s crowd, and that existing appointments would be rescheduled for another day if we stayed. So our segment kept together, slinking forward into a building and up a set of stairs to people with clipboards who I thought were taking names for new appointments.

Mike the security guard corrected me: You’re getting the vaccine.

“I feel really excited,” Urban said when she learned of the surprise. “I don’t have insurance. I’ve been super cautious. I live alone and it’s super isolating. I’ll have to take precautions, but it’s a step forward toward having more autonomy in my life.”

We entered a banquet hall subdivided by a warren of folding tables and dark partitions, with burgundy damask above an empty stage, the klieg lights shining on us instead of performers. Nurses in white smocks had no idea of the snafu farther down the line; the nurse who checked me in expressed shock behind her face shield when I told her thousands of people were headed her way. Another nurse said it was busy, but less busy than the Javits Center in Manhattan where she worked and thousands are jabbed every day.

A young nurse named Diana, who displayed her name on a notecard in soft green curly script, asked me a litany of questions about my recent health, to which I answered, “No, no, no, no” as fast I could without being rude. I asked if I could take a selfie, demurring that I’m not “a selfie guy,” and she reassured me most guys aren’t. Then she cracked open the blue plastic sheath on a syringe, drew the last of five doses from a tiny glass vial, swabbed my left shoulder, and softly inserted the needle. Four seconds later, I was vaccinated.

I was directed to the other half of the hall that was turned into an observation room for possible allergic reactions, with numbered folding chairs spaced far apart. “It feels like school,” I told another person, recalling junior-high assemblies. I bargained a 15-minute wait down to 12 with the nurse who was monitoring us and briskly left.

When I walked back outside, the line was no shorter than it had been. Another volunteer told a small crowd buzzing with frustration that the site was practically shutting down, with the rest of the shots being prioritized for the elderly and disabled. That calmed the group considerably, whose shrugs acknowledged that their sacrifice may not have been in vain.