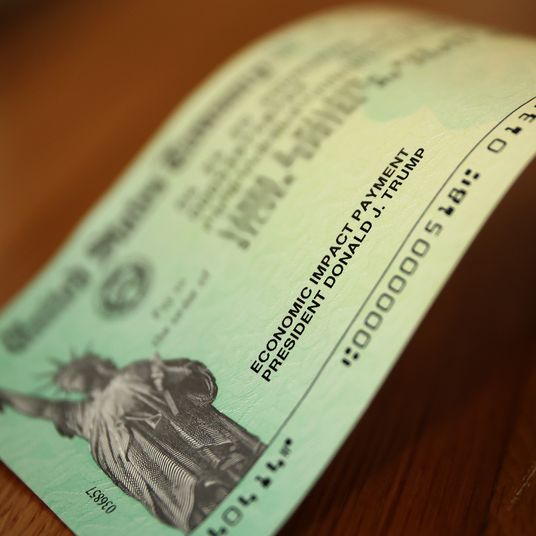

The U.S. government’s current stopgap spending measure expires on March 14. But if your instinct is to scoff at the latest talk of a government shutdown as a boy-cries-wolf phenomenon, that’s understandable. Virtually every time appropriations are due to lapse, some faction has a vested interest in threatening a shutdown to add leverage to their position on matters big or small. Yet, the last time one actually happened was in 2018–2019, when Senate Democrats exercising a filibuster threat defied Donald Trump’s demands for additional “border wall” funding. The impasse lasted a record 35 days, until Trump figured out a way to get his money while bypassing Congress. Legislative leaders have since gone to extraordinary lengths to keep the government open when all looked lost. Most notably, in the fall of 2023, House Speaker Kevin McCarthy cut a last-second spending deal with Democrats that led directly to the loss of his gavel as angry GOP hard-liners supported a motion to vacate the chair.

So why would this time be any different? There are several reasons.

First, anything other than a simple extension of current spending levels across the board takes a lot of time and effort. Despite their apparent powerlessness, Democrats can block appropriations measures with a Senate filibuster, as they could in 2018 when Republicans had a governing trifecta as well. So they have to be cut in on any deal. And with just over three weeks until the money runs out, there have been virtually no real negotiations. There’s no “top-line” spending deal in sight dictating total appropriations, much less the deals over individual items. There’s also a total lack of agreement within the GOP caucuses, never mind across the aisle, as to whether the goal remains passage of the 12 individual appropriations measures covering all federal operations (as most conservatives prefer, even though it hasn’t happened since 1996), or some big fat “omnibus” bill combining appropriations, or yet another “continuing resolution” that just extends current spending levels until the end of the fiscal year in September. There’s obviously a lot going on in Washington right now, but enacting appropriations is one of the very few things Elon Musk or Russell Vought can’t do for Trump — yet time will soon run short.

Second, the two parties are perhaps farther apart than ever in their ideas about appropriate spending levels for this or that government function. Trump didn’t campaign on an extreme austerity budget, but that’s what he seems to be insisting upon in office, and all the saber-rattling from both DOGE and the Office of Management and Budget suggests he’s not going to be willing to wait for the next fiscal year to begin very deep cuts in programs and personnel of which he does not approve. Signing a same-old-same-old bipartisan spending measure would conflict pretty dramatically from his overall posture at the moment.

But the third and most important reason a shutdown might happen this time involves Democrats. Typically, as the “party of government,” Democrats can be counted on to supply whatever votes are needed to keep the federal government open. But now they are understandably horrified by the ever-proliferating power grabs undertaken so quickly by Trump and his agents — and by what they are doing with that power. Yes, they may be able to count on the federal courts to rein in DOGE or OMB or individual agency heads who are running wild, but (a) that will take time, (b) the outcome isn’t certain with a Trump-friendly Supreme Court at the end of every strand of litigation, and (c) passively watching the whole crazy show doesn’t reflect very well on congressional Democrats themselves, whose constituents are frantic for them to do something.

Democrats are already by definition shut out of the long-term budget decisions congressional Republicans are pursuing via budget-reconciliation legislation (which will also now, it appears, include the debt limit increase that once looked like a source of Democratic leverage). So getting a lot of concessions from Republicans in March is a no-brainer. Such concessions might go far beyond spending levels into subjects like reasserting Congress’s control of appropriations or reining in DOGE. The odds of those dynamics playing out to a successful conclusion without at least some lapse in appropriations seem low.

Indeed, negotiations, once they finally get moving, over appropriations could represent the only serious bipartisan activity we will see this calendar year. There could be a lot at stake beyond keeping the federal government open. And that’s why it will probably close.