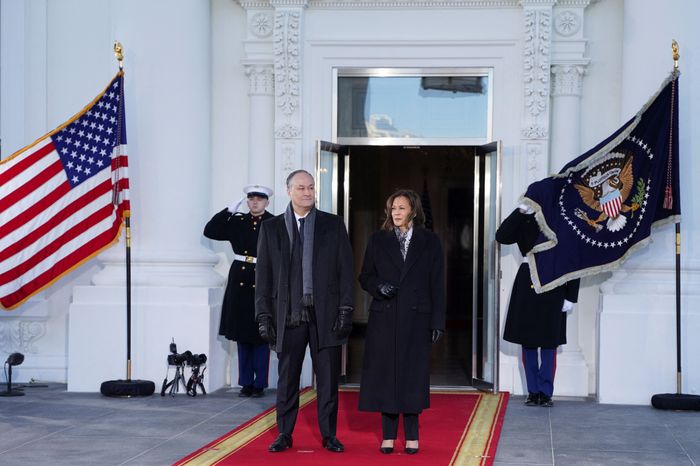

On the final Friday of her vice-presidency, Kamala Harris partook in one last ritual. She looked disbelievingly as she walked into her ceremonial office in the Eisenhower Executive Office Building, across the street from the White House, and saw a large group of her former staffers arrayed in front of her desk. She was there to sign its drawer, just as more than a dozen of her predecessors had done.

She peered out with a tight smile as she scanned the room and thanked the team for its years of labor. Harris promised not to recount “the laundry list of our accomplishments. We know what they are.” But she insisted, suddenly laughing, that the work was not done: “You all know me, because we have spent long hours, long days and months and years together. It is not my nature to go quietly into the night. So don’t worry about that.” A low, brief chuckle rippled across the roomful of loyalists. She didn’t elaborate. Then again, no one had asked. Behind Harris, her husband, Doug Emhoff, looked on with a labored grin of his own. As she approached the desk to sign it, he fished out his iPhone from a pocket and started taking photos. He captured her with Sharpie in hand, then a close-up of her signature, and then, at her urging, a selfie of the couple with the gathered aides. It was as if they needed their own documentation that they had been there.

As the room emptied, Harris’s pledge to her staff lingered in the air. A reporter tried asking what was next for the VP, and she demurred, saying she’d “keep you posted.” It was the most she had said about the topic since losing to Donald Trump two months earlier, but she had given it more thought than she let on.

Not long after the election, Harris privately began talking with family, longtime friends, and her most devoted aides about the path ahead. After a few weeks, her instructions to a few trusted advisers were clear: They should keep her options open and specifically not make any plans that could close the door to a 2028 presidential campaign. This only felt natural. She’d been running for the job since early 2019, and no one just walks away easily after getting as close as she just had.

Of all the options open to Harris, maintaining a White House–ready future would require the most groundwork, so the instruction was mostly practical; an alternative interpretation would be to act like she could run again until she decides otherwise. But according to multiple people who are close with Harris and have spoken to her since November 5, she believes she has three plausible choices. Each would include personal and political obstacles, and each would require her to make a series of mutually exclusive decisions about her life in the coming months. She could run for president again in 2028 or she could run for governor of California in 2026 or she could close the door on electoral politics after two decades in office and 35 years in public service. Harris, who is 60, is hardly decided.

In the first weeks after the election, friends occasionally found themselves listening as Harris, somewhere between frustrated and befuddled by her loss, asked questions about how Trump won and what her campaign could have done differently. Brian Brokaw, who advised Harris as she rose in California politics, says, “It’s a total psychological mindfuck. You have to convince yourself you’re going to be president in order to prepare yourself, and then it doesn’t happen, so there’s a lot of processing that’s taking place. And you have to deal with the angry donor class, you gotta sit back and watch as staff and consultants snipe at each other.” Only recently has Harris seemed looser around close allies, less consumed by the questions of why she lost.

Making up her mind about what comes next began informally not long after the election, when she and Emhoff retreated to Hawaii for a week. They holed up in a quiet Big Island rental featuring five bedrooms, a pool, and enough space that they never felt compelled to leave the property as they talked. She continued the casual discussions with an expanded circle of close associates when she got back home. Her friends and political allies contribute to a wide spectrum of opinions about her best next moves, ranging from another run at the presidency to a speedy retirement far from the nearest Wi-Fi router. But closer to her, advisers have made sure their counsel is almost entirely private.

Harris’s innermost circle of trust is the same as it has been for years and starts with family. Emhoff is joined by Harris’s sister, Maya, a former policy adviser to Hillary Clinton who helped steer her ill-fated 2020 campaign; Maya’s husband, Tony West, a former Obama Justice Department official turned top Uber lawyer and frequent campaign-trail sounding board; and their 40-year-old daughter, Meena. Rounding out the central brain trust are Harris’s close friends Reginald Hudlin, a filmmaker, and his wife, Chrisette, who first set up Harris with Emhoff. Harris has also kept some of her recent aides especially close. Lorraine Voles and Sheila Nix, her official and campaign-side chiefs of staff, who are credited with reforming Harris’s West Wing office and reputation in the second half of her term, are in the fold. So are former Joe Biden advisers Jen O’Malley Dillon, who ran Harris’s campaign, and Cedric Richmond, the former Congressional Black Caucus chairman who worked in the White House. She has also kept a handful of longtime advisers dating back to her time in California in the conversations as well as some veteran Democratic operatives who have offered her advice for years, like Minyon Moore, a former aide to the Clintons. In her final weeks as VP, as Harris heard unsolicited advice from donors, she reached out to some carefully selected allies to hear their thoughts, too. Among them was Hillary Clinton, the other would-be first woman president who lost to Trump and who also famously wrestled with how to manage life after her campaign.

Harris has dropped no hints about her thinking and given no interviews, leading well-wishers who know her to float creative suggestions through intermediaries: Perhaps she could become some sort of portfolio-free stateswoman, or an above-the-fray adviser to Democrats in search of policy or political guidance, or simply a very rich member of many corporate boards. Other Democrats have less sparing advice: Maybe she should just go away.

She held off on convening any formal discussions about the future while she finished her time in government, instead attending to the circumscribed duties of her lame-duck office and planning one last official trip to visit overseas military installations before canceling it to assist the administration’s response to the California wildfires. But even as Harris performed her official duties, the topic of her future proved inescapable. In her final days in office, she called foreign leaders like Emmanuel Macron of France and Olaf Scholz of Germany, about maintaining support for NATO and for Ukraine in its war with Russia. She connected with a few others whom she’d gotten to know well, including the presidents of Kenya and the Philippines, and received thanks from the prime ministers of Barbados and Jamaica. According to people familiar with the calls, some of the heads of state told Harris they’d been watching as she certified Trump’s election and spoke of their relief at witnessing a peaceful transfer of power four years to the day after Trump’s mob attacked the Capitol. All invited her to visit their countries as a private citizen. Most made sure not to hang up before asking her one last direct question: What, exactly, were her plans now?

Harris wants space to think it all through, to see how the world and country react to Trump’s return. In one scenario, her party might welcome Harris back as an important liberal voice for a dismal time — especially if she’s willing to articulate a clear vision for how Democrats should reconnect with the voters they’ve lost. She has some goodwill to collect on; she did just earn 75 million votes and raise over $1 billion. “She repeatedly says, ‘We have lots of work to do. Let’s keep at it,’ and so she is not shrinking back. She will find her way. She will know what to do. She has lots to offer,” Susie Tompkins Buell, a major Democratic fundraiser and longtime Harris supporter, told me recently.

The argument for acting like she might want to pursue the presidency again is straightforward. For one thing, it’s the same posture any Democrat eyeing 2028 might reasonably take at this point, especially since so little is known about how the country will reshape itself in response to Trump 2.0. Harris has more hands-on experience than any of the likely alternatives. If anyone wanted to argue that she already had her shot, Harris could argue that the campaign she just ran was hardly her own — it was a frantic 100-day sprint abruptly inherited from Biden.

Already, though, large swaths of Harris’s own party have evinced desperation to move on entirely from the Biden years to something new — not just in repudiation of the administration, of which Harris was a prominent part, but also of its preceding resistance-style response to the first Trump term, which put Harris on the national stage in the first place. It’s no stretch to think that even her allies may feel they must confront this Trump-dominated world with a new set of champions who are free of Biden-era baggage. Not long before the inauguration, I was talking about the future with a longtime, very senior Democratic operative, someone who just recently had been optimistically planning out life under a Harris presidency. At one point I raised the topic of the VP’s next moves. “Oh,” the operative said. “I don’t care.”

Harris has thus far been mostly spared in the blame game that has coursed through the party — Democrats often reserve brutal treatment for their losers, and Biden has gotten the brunt of opprobrium for sticking around longer than he should have. Not one of the close Harris allies I’ve spoken with expects this dynamic to last. Instead, they are bracing for a harsher reconsideration, some version of the unsparing friendly fire that tanked the reputations of John Kerry and Al Gore. “The shit is still coming,” one adviser told me. “It’s a very, very tough road ahead.”

One person who is intimately familiar with what that’s like is Hillary Clinton, whom Harris started to get to know when she first got to Washington in 2017. She occasionally called the former secretary of State for advice as a senator, then as VP. The bond deepened last July when Biden abandoned his reelection campaign and the Clintons endorsed Harris almost immediately, beating other party machers like the Obamas and Nancy Pelosi. Since November, Harris and Clinton have spoken on multiple occasions about their exceedingly rare shared experience and about how to think through the future; in December, Harris quietly slipped out of her official residence at the Naval Observatory in Washington and over to Clinton’s home a few blocks away to chat and celebrate at a private reception for the former secretary of State after Biden awarded her the Medal of Freedom.

A few days later, Harris was surprised to learn that Biden had told USA Today he still thought he could have won reelection. Harris had gone to great lengths not to distance herself from the unpopular Biden during the administration or while running the campaign she inherited from him, even infamously telling The View hosts that “not a thing comes to mind” that she would have done differently from her boss. Biden didn’t elaborate on his analysis in the interview, but some around Harris couldn’t help but wonder if he meant to blame her for Trump’s victory. “I did find it surprising, but I can’t say I’m shocked,” one person close to her told me not long after. Though Biden and Harris almost always publicly appeared in lockstep, their loyalists at times clashed behind the scenes, and some close to Biden were hardly shy with their doubts about Harris’s political viability. The ex-president and his closest advisers have remained raw over the way Democrats urged him aside last summer. When I asked how Harris herself had taken Biden’s words, her associate spoke slowly and chose her words very deliberately. “It’s … unfortunate,” she said.

In recent weeks, some people who have known Harris for years have reminisced about how happy she was when Air Force Two flew away from D.C. and approached California. They’ve talked about the time, a decade ago, when she was weighing whether to run for the Senate or the governorship. She chose Washington, but Sacramento had been on her mind for years, and it recently returned. A handful of Harris’s California allies have encouraged her to consider that running the world’s fifth-largest economy might be a fitting final career move.

News that she could run for governor next year was at first greeted cautiously back home. Though no one doubts she would be the immediate favorite in the race, some have questioned whether she would enjoy the specifics of the gig. Los Angeles Times columnist George Skelton was blunt: “She’d probably be miserable in her work” if she saw it as a consolation prize or a stepping stone back to the White House, he wrote, pointing out that she’d have to confront the housing crisis, crime, a budget mess, homelessness, and a water shortage. This was before the fires.

And a gubernatorial run would not be drama free. Harris would effectively be big-footing her friend, Lieutenant Governor Eleni Kounalakis, who is contending to be the state’s first woman governor. She would also potentially stymie former L.A. mayor Antonio Villaraigosa’s bid to be the state’s first Latino executive. Meanwhile, other possible candidates, including former congresswoman Katie Porter, state attorney general Rob Bonta, developer Rick Caruso, and Biden Health secretary Xavier Becerra, are waiting to see what Harris will do. “There are ten people holding their breath out here,” says Barbara Boxer, who preceded Harris in the U.S. Senate.

Though she has frozen the field for now, most of Harris’s allies in California and Washington have recently downplayed the likelihood of a run. Some advisers have argued to her that the governorship may be a huge job but it’s a step down from the vice-presidency. And no one believes she could realistically run for president again if she goes for governor first. “You have to really want to do it, and I don’t know the answer to the question: What is in her heart?” says Boxer. “Because there’s a huge, huge difference between being governor or president.”

Californians looking for evidence that Harris might still opt for a prominent local role saw plenty on Monday, when she landed back in Los Angeles after handing over the vice-presidency. Her first stops, with Emhoff, were to thank firefighters and serve food to people who’d been affected by the fires in Altadena. Local news dissected her appearance before she even got back to her own house in a neighborhood that had only recently been reopened to its residents.

For a few days in January, Harris and Emhoff weren’t sure they would have a home to return to. Their place in Brentwood was inside an evacuation zone, and at times during the worst of the fires, Harris relied on neighbors for reports on the house’s status. It survived.

But another home has also been on Harris’s mind. The couple has been seriously exploring the Manhattan apartment market so they can become a bit bicoastal. They have considered different kinds of uptown units — “Page Six” was recently tipped off to Emhoff’s tour of a big condo near Lincoln Center — and have been working through logistical questions, including security concerns. (Former vice-presidents get six months of Secret Service protection, but that can occasionally be extended depending on risk levels.)

A secondary East Coast base may be helpful for their travels. Harris is likely to give some paid speeches, and she’s already fielded inquiries about writing a book. Emhoff, a lawyer, has spoken about taking on clients again and maintaining a public profile so he can keep up his work combating antisemitism. Harris has talked with staffers about setting up some sort of organization to fund her continuing work, but they haven’t settled on the nature of the work or the type of organization. Some aides have whispered about what her ongoing friendship with the billionaire philanthropist Laurene Powell Jobs could mean for her future: Perhaps she could join Jobs’s Emerson Collective in some advisory capacity. Nor has she decided on how many speeches to give or whether to write a book. “If she’s going to be thinking about running for president, it freezes everything for two years,” says one person familiar with her thinking. Biden, for one, turned down a $38 million speaking contract after leaving the vice-presidency to avoid the perception of corruption ahead of his 2020 run; Harris, who has written two books, knows that a pre-campaign volume is a very different kind of read, and a much worse seller, than a post-career tell-all.

Harris has no shortage of friends advocating for each of her options, including Door No. 3. “She probably knows, deep down, that odds are she’s not the right person to carry the mantle, because she just did,” one former senior aide told me. “She understands that timing is everything — she’s been a beneficiary of that through her whole career. So she probably understands that barring some unforeseen circumstance, people will probably want to move on to something new.”

A few hours earlier, another of her old high-level staffers had called to spell out why he was arguing for a soft drift into comfortable retirement. He could see the argument for another presidential run, he says, and thought she could win the governorship without breaking too much of a sweat. But, he continued, “when you look at what the other options could be” — possibly losing a third presidential race, perhaps being miserable as governor — “as a private citizen, she could have a pretty good life.”