“They’re all technofeudalists, they don’t give a flying fuck about the human being. And I don’t care if you’re Black, White, Hispanic, Chinese — they don’t care,” a prominent political commentator recently told New York Times columnist Ross Douthat. “They don’t believe in this country. They believe in this country right now because it protects them and provides some benefits to them.”

The commentator continued: “And the apartheid state of Silicon Valley thinks we don’t need our greatest resource, which is the American citizen. They’d rather import basically indentured servants to work for a third less and have an apartheid state. And then as soon as they can replace them with digital serfs, they will do it.”

Not long ago, it would have been conceivable for a leftist to utter these words. But in the new Trump age, such arguments have fallen to Steve Bannon. A vicious operator with a populist streak, Bannon is reviled by almost everyone on the left for his conspiracymongering and furious support of Trump. But Bannon has also made it his mission to destroy Elon Musk, the new bête noire of Democrats. Liberals who share that goal — and want to boost their working-class credibility — might want to pay attention to how he’s doing it.

Beyond the Times, Bannon has found many other opportunities to lash Musk. In an Italian newspaper, he called Musk a “truly evil person” and brought forth, most notably, his claim that he and his allies are “technofeudalists.” Bannon’s attacks are potentially potent because he understands the stakes of this battle. Put simply, Musk cares far more about his business and tech interests than the fate of working-class America. Bannon also knows Musk is more vulnerable than he looks. If the Democratic Party hopes to cut him down, they’ll have to do more than bray about his fortune and his “co-presidency” with Trump.

The left’s instinct to attack Musk, at least, is correct: There are plenty of signs the world’s richest man is not terribly popular, and DOGE’s assault on the federal bureaucracy is not something most Americans are overly excited about. Musk isn’t any kind of folk hero or Ozymandias brought to life. Onstage, he exudes a striking anti-charisma, and he’s probably among the worst public speakers ever handed a prominent role in any presidential administration.

Democrats make a few mistakes with Musk. For one, they play into his myth. Yes, he is an oligarch, but he is spoken about more as a world-historical dark genius than what he truly is: a uniquely ambitious but ultimately very lucky man. He has feasted on government contracts for decades. Tesla is a successful electric-car company, but that’s all it is — a car company. Plenty of Americans still drive Fords, Chryslers, Mitsubishis, and Hyundais, and their CEOs are not treated as hypermodern gods. SpaceX, Musk’s aerospace company, is impressive for what it is, but it’s notable that much of what it accomplishes is only possible because the federal government decided to offload many of NASA’s former responsibilities to the private sector. More than a half-century ago, federal engineers took us to the moon, and now Musk wins wild plaudits for sending rockets and satellites into low orbit—that is, when they don’t explode. Neuralink might be the most remarkable of his innovations, if one that is still far away from wide-scale application.

Bannon, in his interview with Douthat, did compare Musk to a 21st-century Thomas Edison, infusing the South African–born CEO with more of an aura than is warranted. But then Bannon cut to the heart of the matter: Musk is a globalist of the first order with only a tenuous loyalty to the United States. He does enormous business with China and rarely, if ever, criticizes its regime. He does not care if cheap Chinese goods flood the U.S. and undermine American manufacturers. The plight of the American worker is of little interest to him.

The “technofeudalist” critique is one that professional Democrats, for all their feints toward populism during the Biden years, have yet to effectively make. This is because the Democratic Party, broadly, was closely tied to Silicon Valley during Barack Obama’s presidency and most of the first Trump term. Tech titans allied themselves with Democrats, and the center left strained to show it was future facing — in part by embracing Apple, Meta, Alphabet, and Twitter. When Bernie Sanders first ran for president, fissures began to form in this alliance. When Trump shocked Hillary Clinton and won the presidency, they grew, with many on the left blaming Facebook for fueling Trump’s rise.

The alliance broke for good during Joe Biden’s presidency, when he appointed Lina Khan chair of the Federal Trade Commission and Rohit Chopra as the director of the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau. Chopra’s CFPB was the first to effectively adhere to Elizabeth Warren’s muscular vision of imposing stricter, consumer-friendly rules on banks and big businesses, and Khan’s FTC enthusiastically sued Google and Amazon, attempting the first vigorous turn toward antitrust policy in many decades.

But Democrats never quite knew how to sell this agenda. Biden, dimming in his 80s, was unable to adequately explain it to the public. When pressed, Kamala Harris seemed wary of the Biden administration’s historic antitrust agenda. She would not commit to keeping Khan at the FTC if she won and had little to say about reining in tech monopolies. Ken Martin, the new chair of the Democratic National Committee, doesn’t seem so different; he recently said the Democrats can still take cash from “good” billionaires who support their causes.

Of course, the Democratic Party can’t unilaterally disarm against an onslaught of Musk, Peter Thiel, and Miriam Adelson cash. What the left must understand, though, is that it cannot be everything to everyone. Trump’s GOP is a brand, and few Americans are confused about what it stands for: restricted immigration, tariffs, anti-elitism, and deep social conservatism that, with the exception of opposition to trans rights, has been somewhat downplayed by Trump since he came back into office. Nate Silver, referring to a recent social-media post, put it rather succinctly: The Democrats can be the party of either Mark Cuban or Lina Khan. It’s very difficult to be both.

What Bannon understands is that Silicon Valley, in the last decade, has grown increasingly anti-human. Its newest marvels, like AI, are no longer greeted with universal acclaim. Jonathan Haidt’s The Anxious Generation, which attached significant blame to the big tech companies for the mental-health crisis among young Americans, dominated best-seller lists, and school systems across the country moved to ban phone usage in the classroom.

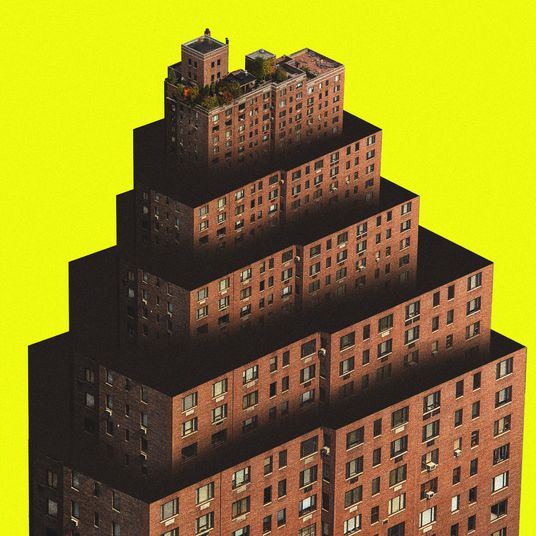

In his 1992 book, Technopoly, the sociologist Neil Postman defined the United States as the very first “technopoly,” a nation where the “deification of technology” would lead to a culture that takes its very orders from tech itself. “This requires,” Postman wrote in his book “the development of a new kind of social order, and of necessity leads to the rapid dissolution of much that is associated with traditional beliefs.” Under technopoly, there are no “moral underpinnings,” no room for ruminating on how these advances might affect the human mind and spirit. Tech oligarchs like Musk celebrate the concept of drastically decreasing human agency. Advertisements for AI programs conceive of the modern human as singularly slothful and shallow, unable to even compose a straightforward work email without the help of an advanced machine.

A few well-known Democrats, like Senator Chris Murphy of Connecticut and Ro Khanna, the Silicon Valley congressman, have spoken about the challenges facing the working class in a dimension not dissimilar from Bannon’s, warning of a “spiritual unspooling” that has made the world’s richest country a land of startling unease and despair. They don’t traffic in Bannon’s rank nativism, either, which is refreshing. What is largely missing, though, is Bannon’s evident fury at elites — very much including the most powerful people in Silicon Valley, despite the fact that they stand behind a president he supports. Even if it’s all performative (Bannon himself is very wealthy), it would behoove Democrats to take the side of the working class against tech oligarchs with that much force and feeling. For now, Musk and his allies are ascendant. Beating back technopoly will be the fight of our time.

More From This Series

- McConnell Finally Defies Trump, Now That He’s Irrelevant

- Trump Ambassador Picks: Who’s in His ‘Diplomatic Clown Car’

- GOP Likely to Hold Senate, No Matter What Trump Does