The skate-inspired clothing brand Supreme built a cult following for its tweaked versions of famous logos. It’s mostly gotten away with this sampling of intellectual property, so it was especially ironic that when Supreme found itself embroiled in a trademark suit this year, it was the one doing the suing. Below, four images that explain how the maverick streetwear company learned to love trademark law.

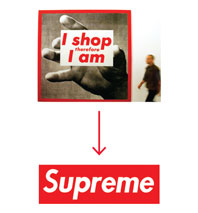

1. The Inspiration

When Supreme’s store opened on Lafayette Street in 1994, its first house-branded T-shirt, a still of Robert De Niro as Travis Bickle in Taxi Driver, helped establish its aesthetic: Take a pop-culture icon, maybe mess with it, maybe don’t, slap it on a T-shirt. Charge $40. Even the brand’s best-known design, its own red box logo, borrowed the typeface and color made famous by feminist Conceptual artist Barbara Kruger. Almost twenty years later, Supreme’s founder, James Jebbia, a 49-year-old British émigré, is now a multimillionaire, and Supreme has stores in L.A. and London and six in Japan. Terry Richardson has photographed Lady Gaga wearing Supreme. Some of its products are now original collaborations: It’s made skate decks designed by Jeff Koons and George Condo and worked with brands like A.P.C., Levi’s, and Comme des Garçons.

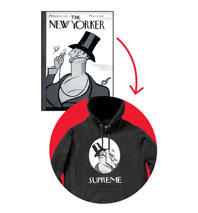

2. The Method

Still, Supreme has retained its early appropriative style: This season, one shirt shows a rewritten Robitussin label. Another takes a frame from The Wizard of Oz. Warner Bros.’s Speedy Gonzales graces the front of a line of forthcoming caps above the phrase adios mutha. Some of these images are licensed; some are not. Supreme produces very limited runs of clothing that often sell out quickly, and most companies don’t bother to lawyer up over 200 T-shirts. Condé Nast certainly didn’t when Supreme put The New Yorker’s mascot, Eustace Tilly, on hoodies and hats in 2011.

3. The Consequences

Some companies do send cease-and-desist orders before the limited run sells out. That’s what happened with the Kings line, featuring “Supreme” in the style of the L.A. hockey team’s logo. “We had to pay them for that,” says Jebbia of the hoodies and hats. “We’ve been wrong, but we deal with it and make it right.” But the logo appropriation is also what makes Supreme’s clothes appealing, not only because recognizing that the respect the wild patch on a jacket plays on the classic Polo Sportsman patch puts you in exclusive company, but also because it helps Supreme maintain its image as rebellious and authentic.

4. The Competition

In 2004, when 22-year-old Leah McSweeney started a women’s skate-fashion line called Married to the Mob, her first T-shirt was a sort of homage: supreme bitch written in the Supreme (via Kruger) style. Jebbia carried the shirts in Union, another store he owned. As Supreme’s fortunes multiplied, so did Supreme Bitch. Rihanna posted pictures of herself in a Supreme Bitch cap. Karmaloop and Urban Outfitters have sold Supreme Bitch items. In January, McSweeney took what would be a normal step for an upstart clothing label: She filed a trademark application for Supreme Bitch. Two months later, Supreme sued McSweeney for $10 million and demanded she remove the offending items from retailers. According to Jebbia, McSweeney’s shirts aren’t just logo appropriation; they’re “trying to build her whole brand by piggybacking off Supreme.” Though he does remember approving the original Supreme Bitch designs, at the time, “I thought it was just going to be a one-off. Now it’s on hats, T-shirts, towels, mugs, mouse pads.” McSweeney has a different take: “There’s this one Barbara Kruger piece that says, ‘Your comfort is my silence,’ and I can’t help but think that I’m being silenced by Supreme with this lawsuit. I don’t have $250,000 to litigate this case, and they know that.”