By most accounts, Donald Trump has been licking his chops at the prospect of running against Bernie Sanders. His GOP allies in particular feel that the Vermont senator’s nomination would spell doom for down-ballot Democrats. Even as national polls show Sanders leading in most head-to-head matchups against the president, his leftist platform and self-description as a socialist provide what some see as a messaging gift: a candidate too radical for the moderate suburbanites whose votes for Democratic House candidates in 2018 were understood as a backlash against Trumpian extremity. The thinking goes that Democrats would harm their “return to normalcy” pitch if they nominated their own zealot — and fatally damage their hopes of retaining their House majority, let alone winning the Senate.

This may be moot in the wake of Super Tuesday. Trump’s less preferred outcome now seems to be the more likely one: a November showdown with Joe Biden. The former vice-president is more conservative than Sanders, hampering the prospects of a down-ballot GOP edge on that front. And like Sanders, he’s led Trump in most head-to-head polls, often by wider margins. Concerns early on within the administration that Trump would face Obama’s VP have led to costly missteps. The president hoped to turn Biden’s family ties to a Ukrainian energy company into an election-year scandal. He ended up offering Ukraine’s head of state aid in exchange for investigating Biden and his son Hunter, triggering a House investigation and a Senate impeachment trial. (Trump was acquitted in a mostly party-line vote.) But while a cascade of Hunter-focused Senate hearings isn’t out of the question as a Republican countermeasure, Trump has other avenues for an offensive in mind.

A preview has come in the form of his recent appeals to black voters — a demographic that’s been instrumental to Joe Biden’s success in the primary. Trump is going to try dampening black voter enthusiasm for Biden by contrasting the two men’s criminal justice records. The framing will be simple: Trump signed a bipartisan criminal-legal reform bill, the First Step Act, and has been generous with his pardon powers toward unjustly imprisoned black people, like Alice Marie Johnson. This was the essence of his Super Bowl reelection ad and much of his State of the Union address. His son-in-law-turned-adviser Jared Kushner maintains that such appeals will resonate with black voters, especially in upper midwestern swing states where the slightest chip in Democrat armor could cost them the region.

Indeed, conventional wisdom holds that because the system harms black Americans disproportionately, they are uniquely susceptible to reformist appeals from politicians. If this is true, it hasn’t been determinative in the 2020 primary: Kamala Harris was a punitive prosecutor in California and enjoyed higher rates of black support than nearly all of her former competitors who’ve since dropped out. Michael Bloomberg, the longtime “stop and frisk” proponent, briefly polled higher among black voters than Sanders. And Biden has been the consensus candidate of most black Democrats ever since he entered the race. But Trump’s is not a meritless strategy. It has the benefit of a soft target. The president’s use of pardons on people like Johnson may indeed be an opportunistic means of laundering his own efforts to get his friends out of prison. The First Step Act may have fallen into his lap because Mitch McConnell thwarted President Obama’s chance to sign a similar bill in 2016; his rhetoric on criminal justice may waffle between applauding second chances and touting the merits of executing people for selling drugs. But while Trump’s status as a self-styled reformer is laughable, Biden’s record is grotesque.

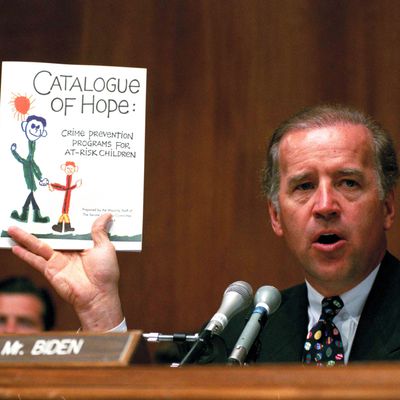

Most of its lowlights occurred in the “tough on crime” 1980s and 1990s, when he was a senator. (His presidential campaign platform calls for reversals of many policies he once championed — including disparities in crack and powder cocaine sentencing, ending cash bail and the death penalty, and providing more alternatives to imprisonment.) But back then, he viciously characterized people who commit crimes as sociopathic “predators” who are beyond rehabilitation. He cast then-President Bush’s escalation of the War on Drugs as lacking “enough police officers to catch the violent thugs, enough prosecutors to convict them, enough judges to sentence them, or enough prison cells to put them away for a long time.” He authored the 1994 Violent Crime Control and Law Enforcement Act — known colloquially as the 1994 Clinton crime bill, but which Biden liked to call the “1994 Biden crime bill” as recently as 2015. Its main legacy is cruelty: It expanded the death penalty, eliminated education funding for imprisoned students, created harsher sentencing guidelines for a wide range of crimes, and increased funding for local police departments and corrections departments.

All of this harmed black communities disproportionately even as black officials — many of whom supported the 1994 bill anyway — were calling for robust investments in social services to supplement their requests for more responsive law enforcement. Biden’s bombast led a national crusade to ignore them. Perhaps more than any other official of the era, he embodied the Democratic impulse to outflank Republicans from the right by locking more people in jails and prisons. He helped catalyze the most dramatic expansion of the carceral state in the history of the country with the highest incarceration rate in the world. He said he was “not at all” ashamed of his involvement as recently as 2016. His more recent apologies for the fallout are no less opportunistic than Bloomberg’s campaign-launch mea culpa for stop and frisk.

Luckily for Biden, this legacy has cost him little. His status as the primary’s front-runner was challenged by Sanders only briefly, and black voters across the South provided the foundation for his Super Tuesday rout. There’s widespread agreement among many Democrats that whatever Biden’s flaws, at least he’s a known quantity. “I know Joe. We know Joe. But most importantly, Joe knows us,” Representative James Clyburn told MSNBC of Biden’s relationship to South Carolina’s majority-black Democratic electorate. Whether this pattern replicates in Michigan and Wisconsin is yet to be seen. In the meantime, Trump is champing at the bit to test Kushner’s hypothesis and position himself as rectifier of Biden’s legislative wrongs. A president whose defining legacies will include resuming federal executions and locking migrant children in cages to punish their parents has no moral standing when it comes to criminal justice, to be sure. But in his wildest dreams he couldn’t have conjured an opponent with less than Joe Biden.