You sort of have to admire Goldman Sachs’s stamina. It’s been what, like, three years since the Abacus lawsuit? TARP has been paid back, Fabulous Fab has already started his second career as a soccer-playing economist, everyone loves Lloyd Blankfein and his furry little beard, and Main Street has moved on to hating JPMorgan Chase.

It would be pretty easy, at this point, for Goldman to be all, “What financial crisis?” and go on with business as usual. And yet, the bank is still flagellating itself for its crisis-era sins and releasing long reports about all the ways it’s going to stop doing Bad Things to its clients. One of those reports, called “The Business Standards Committee Impact Report” [PDF], was released at Goldman’s annual meeting today. It’s a fun read!

There’s not much new in the report, per se. Goldman’s Business Standards Committee (basically a task-force it convened after the embarrassing scandals of the crisis) is three years old, and an earlier report along the same lines was released in 2011.

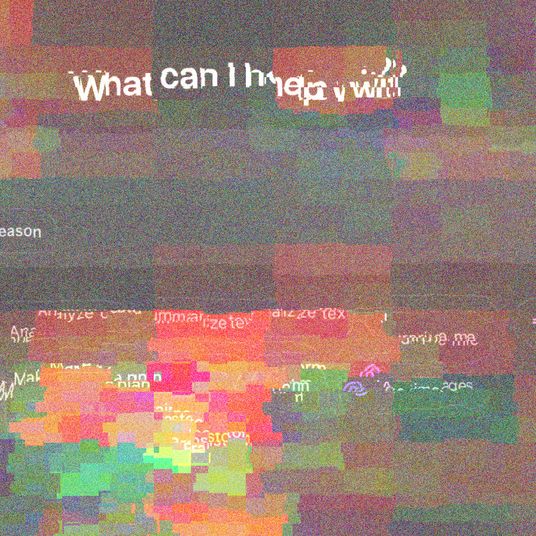

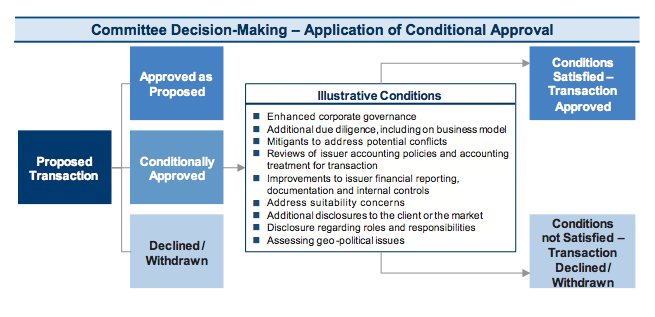

Essentially, what this new report says is that Goldman is taking steps to avoid the many flavors of wrongdoing of which it is often accused, like taking multiple sides on a deal or selling complex investments to clients who can’t fully understand the risks involved, by making employees ask for permission before doing stuff that clients might find objectionable or confusing. As Reuters put it, “Clients will have preapprovals for a certain ‘transaction class’ - or matrix - along the lines of deals they have already done with Goldman. If a proposed transaction falls outside that matrix, it gets routed to a ‘suitability’ matrix that determines whether the client’s profile makes him eligible for the deal.” There is also a fancy site that outlines the process.

But, of course, you can’t just say that and be done with it if you’re Goldman. Because you have spent years writing this report and paid consultants and lawyers a lot of money to help you write it, you have to put in some charts. And so we get this fine flowchart:

What does this mean if you’re a Goldman client? Probably not a whole lot. If Goldman was going to sell you a complex thing you don’t understand before the financial crisis, it’s probably going to sell it to you now, albeit with some extra paperwork. And there are many shades of these things. Does it count as preying on unsophisticated investors, for example, if you’re selling a fee-heavy fund-of-funds to retail clients without telling them that hedge funds have done terribly for the last four years and that because of the additional fees associated with a fund-of-funds they’re even less likely to make money by investing in your fund than just buying a low-fee index fund? You could presume that people should know that by now, if they’re investing in mutual funds; you could also presume that people smart enough to buy mortgage-backed CDOs should know that there’s a chance those CDOs have been designed for failure by a hedge-fund manager on the other side of the trade.

What I’m saying is: There’s probably no Business Standards Committee in the world that could both completely reassure Goldman’s clients they won’t be taken advantage of while also allowing Goldman to perform its core business functions profitably. But the report is a good CYA move; now, when accused of its next offense against muppets, Goldman can point to the chart above and say, “See? We have a matrix!”