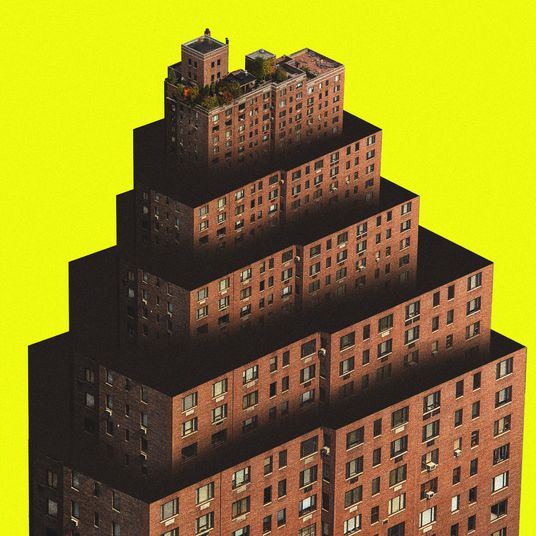

In an article that appeared in the February 2 issue of New York Magazine, I wondered whether gentrification is really the toxic cloud it’s usually made out to be. Focusing on a small business in Inwood, a community organization in Bedford-Stuyvesant, and an affordable housing development for artists in East Harlem, I argued that efforts to improve a neighborhood from inside and the arrival of new, more affluent residents from outside are two aspects of the same process. “Gentrification can be either a toxin or a balm,” I wrote. “There’s the fast-moving, invasive variety nourished by ever-rising prices per square foot; then there’s a more natural, humane kind that takes decades to mature and lives on a diet of optimism and local pride.”

That article, and a subsequent discussion on WNYC’s Brian Lehrer Show, triggered scattered gusts of commentary that whipped around local websites, Facebook, and Twitter. Much of the reaction was positive, some of it outraged. The most incisive zeroed in on points that I couldn’t fully address in the print magazine’s limited space. So now I’ve returned to the topic and tried to distill the splatter of posts, tweets, and comments into an imaginary dialogue with a skeptical reader:

You try to distinguish gentrification from displacement, but they’re really the same thing.

Only if you define them as synonyms. Gentrification is the process in which new residents move into a neighborhood, raising income levels. One place that’s happening without displacement is Hunters Point South, where large residential towers with a lot of affordable housing are rising on abandoned industrial land.

You’re just advocating the trickle-down, rising-tide-lifts-all-boats theory that has created massive inequality.

Not at all. Many of the improvements to struggling neighborhoods have come from local, grass-roots activists wielding political clout to get stuff done. To consolidate those gains and to spread their benefits equitably, we need a more powerful set of tools to create affordable housing:

- Mandatory inclusionary zoning, or, at the very least, new incentives to replace the standard 80/20 model, such as Essex Crossing, the planned affordable housing development on the Lower East Side

- Regulations locking in affordability controls so that they don’t expire

- Vigilance, to ward off another round of predatory lending and foreclosures

- Expanded community land trusts

- A much wider network of supportive housing, so that the chronic homeless don’t spend years in “temporary” emergency shelters

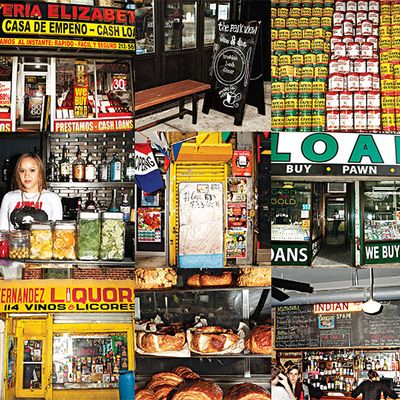

Businesses in gentrifying neighborhoods are affected too. New zoning on the Upper West Side limits the size of new storefronts and tightens restrictions on banks; it’s worth exploring whether that experiment can be replicated in other parts of the city.

You’re minimizing the suffering of people who get forced out of places they have lived for decades. Don’t you believe people have a right to stay where they are?

I do, but it’s not an absolute right. The only way to guarantee it would be to pass new universal, citywide rent control legislation — a move that, politically, is in the realm of fantasyland. On the other hand, dysfunctional cities and neighborhoods force people to stay where they are: That’s the definition of a ghetto.

You hint that the gentrification is the only force preventing urban decay. But New York’s not about to go the way of Detroit just because a few new luxury condos don’t get built.

Of course not, but the danger of renewed urban decline does continue to lurk. Many cities around the country are suffering the opposite problems from ours, and there is no guarantee that the gains New York has made in restoring its economy, keeping crime down and providing services won’t be reversed. Gentrification isn’t just a byproduct of prosperity; it’s part of the engine.

You’re fantasizing about gentrification by a middle class that no longer exists. Now we’re afflicted by a new strain of super-gentrifiers, the migratory ultra-rich who pay anything for real estate but little in taxes, and leave their pieds-a-terre empty most of the time.

Astute, but overstated. The plutocrats snapping up duplexes a quarter mile above 57th Street aren’t the same people driving up prices in Bushwick.

No matter what you say, you can’t get around the fact that the most vulnerable people in New York are those (largely African-American and Latino) who live in unregulated housing, have no protection from eviction, and no clear path to economic stability. Gentrification can destroy their lives.

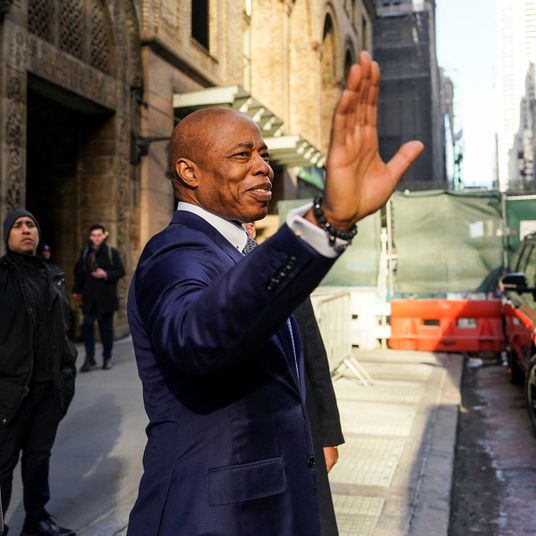

That is totally true — which is why we need to support Mayor de Blasio’s ambitious affordable-housing goals and hope that he has the capacity to achieve them. But subsidies won’t solve the worst kinds of inequality, preserve the middle class, or relieve pressure on the poor. New York needs policies that will stimulate the construction of large amounts of new unsubsidized housing in neighborhoods that are unlikely to become “hot,” especially in Queens. There is enough land to do this, if only the forces of NIMBY could be tamed. In the 1940s, developers put up middle class housing in every borough, and there should be ways to make that happen again. I have some limited hope in the possibilities of modular construction to lower building costs, but that’s certainly not a cure-all.

Rich liberals love to talk about socioeconomic diversity so long as they’re the ones doing the diversifying. But when homeless shelters start coming into their neighborhoods, suddenly they’re worried about property values.

Socioeconomic and ethnic diversity is a civic virtue in high-income neighborhoods just as much as in low-income neighborhoods. The housing projects that now find themselves in wealthy areas predated gentrification of course, but they do have the welcome, if unintended, effect of maintaining significant populations of low-income residents in high-income areas.

That doesn’t mean the Upper West Side needs to accept a spate of poorly run “emergency” shelters for which the city pays preposterously high rent. But if a responsible nonprofit organization opened a well-managed supportive housing building similar to Common Ground’s The Hegeman in Brownsville, it would fit right in.

What about a neighborhood’s character? Are you willing to see that get erased?

This gets us to a fundamental philosophical point: I believe that nobody owns a neighborhood or gets to control its character, and nobody has a moral right to make others feel like they don’t belong. That principle is what makes New York great. New arrivals can become New Yorkers in an instant, simply by being here. Telling people they are not welcome in some part of the city because of who they are, how much they earn, or what language they speak is wrong, regardless of the circumstances. That same territorial sense of protectiveness kicks in when nations protect their culture through hostility to immigrants, institutions discriminate by invoking their history, and communities try to maintain segregation.

Character evolves naturally, and it dissipates the same way, through a combination of pressure and economic success. Jewish neighborhoods became less Jewish, Italian neighborhoods less Italian, Dominican neighborhoods less Dominican, poor neighborhoods less poor, and, yes, rich neighborhoods less rich. This happens partly because other groups move in, and partly because second and third generation immigrants disperse, making way for new populations who will eventually regret the erosion of “their” neighborhoods, too.