Eleven days before Donald Trump took office, I wrote a column with the slightly hedged but still hyperbolic headline “Obamacare Repeal Might Have Just Died Tonight.” While the “might” was doing a lot of work, my argument was that the GOP’s clearest and easiest path for repealing Obamacare had fallen short, which would force Republicans to attempt to forge a vastly more difficult path. That is what has happened since, and that is why the cause of repeal has been dying a slow and painful death. John Boehner — who repeatedly led his party to election victories on the promise that they would repeal Obamacare! — has now admitted repeal is “not going to happen” and “most of the framework of the Affordable Care Act” would remain in place.

Let’s back up and go through how this has happened. As soon as the immediate aftermath of the election, it could be seen that “repeal and delay” gave Republicans the easiest method for destroying Obamacare. The attraction of repeal and delay is that it did not require Republicans to cobble together majorities in both chambers to support any particular alternative plan, which — despite repeated promises and assurances of imminent success — they had failed to do since the legislative debate on health care began in 2009. Repeal and delay merely required finding 218 House Republicans and 50 senators to defund Obamacare on the premise that something, to be determined later, would be better.

But several Republicans expressed reservations about repealing the law without having any clarity about its replacement, if any. By January 9, repeal-and-delay had enough opponents — Republicans could only afford to lose two votes in the Senate — that the party’s leaders would have to scrap the plan, which they did.

The Republicans’ new strategy is to stage a single vote that would repeal Obamacare and simultaneously put replacement measures in place. A group linked to Mitch McConnell is trying to whip up support for this by circulating polling showing that just 17 percent of the public supports repealing Obamacare without an immediate replacement plan. What’s important about this is not the polling result itself — independent pollsters found the same thing since well before the inauguration — but the fact that Republican leaders are now emphasizing it, rather than pretending it’s not true.

Their professed hope is that the replacement plan will give Republican members of Congress something positive to offer in the wake of killing Obamacare. The trouble for them is that attaching a replacement bill to a repeal bill makes the vote much, much harder. Now that their best chance to repeal the law is gone, the remaining options are all fairly desperate.

One well-known problem is that Republican members of Congress do not agree with each other on the parameters of a replacement. Conservatives have demanded a repeal of Obamacare’s Medicaid expansion, but several key senators — most recently Lisa Murkowski — have adamantly opposed such a move. Hard-core conservatives oppose the use of refundable tax credits to subsidize coverage as “Obamacare lite,” because they reward low-income moochers who do not deserve government help. Nor do they agree on whether the law should ban subsidies for any health-insurance plan that covers abortion.

A second, much deeper problem is that the beliefs Republican members of Congress do agree on are not shared by their voters at all. The Kaiser Family Foundation extensively interviewed Trump voters who have Obamacare to ask what features they would like changed about the law. Most of the voters like Medicaid, and dislike the fact that exchange plans have high deductibles. A KFF poll finds that 84 percent of Americans, and 69 percent of Republicans, want to keep the law’s Medicaid expansion. Meanwhile, the House Republican plan would slash funding for Medicaid and massively increase insurance deductibles. A belief in higher deductibles is the conservative movement’s central health-care policy conviction. Conservatives believe that forcing consumers to have “skin in the game” — giving them a financial incentive to use their bargaining power to hold down the costs of their own care — is the singular feature the health-care system most needs.

Republicans were able to paper over this yawning chasm between what their base demands and what their elites are offering for the last eight years only because they have been able to avoid a specific alternative. Republicans attacked Obamacare for its high deductibles, and Trump promised a replacement that would give everybody better coverage for less money. But their proposals would do the opposite. Multiple sources report that the House Republican replacement plan was supposed to come out this week, but was delayed after an initial analysis by the Congressional Budget Office yielded a horrific score. Their plan would cut the average subsidy level for a person buying insurance on the exchanges from $6,314 to $3,643, according to a preliminary calculation by the liberal Center for American Progress.

This is not like getting a bad SAT score, where you can come back later after some studying and a good night’s sleep and maybe get a better score. Republicans oppose the taxes on the rich that help finance Obamacare, and are committed to their repeal. But this forces them to find a funding source that is not limited to the rich. The mechanism Republicans favor is scaling back the tax deduction for employer-sponsored insurance. It would affect far more people than the one percenters who have to finance Obamacare. Just how many people would face higher taxes depends on just where Republicans set the threshold of insurance plans to tax — they could tax only the most expensive plans, limiting the number of people they’d hit, but also limiting the amount of revenue they could yield to finance subsidies. Or they could get more revenue by taxing more peoples’ employer-sponsored insurance. The trade-offs are brutal either way: tax lots and lots of people, provide woefully insufficient insurance, or some of both.

Altering the health-care system is extraordinarily difficult. Health-care reform failed under Harry Truman, Lyndon Johnson, Richard Nixon, Jimmy Carter, and Bill Clinton because the system is almost impervious to change — people who have access to medical care are terrified of losing it, and the people who sell them that care are loath to lose their livelihoods. Obamacare was not a perfectly designed law, but it did reflect a kind of political genius. It found a way to pay for access for the uninsured with minimal disruption to the status quo. Obamacare did create some losers: The very rich pay much higher taxes, and young, healthy people have to pay higher premiums on the individual market. (The latter could one day become winners under Obamacare should they grow unhealthy or un-young.) They made a lot of noise — remember the media freak-out over the tiny number of people who lost their plans in the individual market? — but they were vastly outnumbered by the winners: millions of people who could now have access to insurance who once could not afford it.

The Republican plan, based on its skeletal outlines, has just the opposite effect. It would create very few winners and an enormous number of losers. One percenters would enjoy lower taxes, and healthy people could turn their Health Savings Accounts into lucrative tax shelters that don’t force them to cross-subsidize sicker people. On the flip side, though, millions of people who get insurance through work would be taxed to finance the GOP plan. Hospitals, doctors, and pharmaceutical makers would all lose business because millions of their customers would suddenly be unable to afford medications and treatments, having been forced onto skimpy, catastrophic plans.

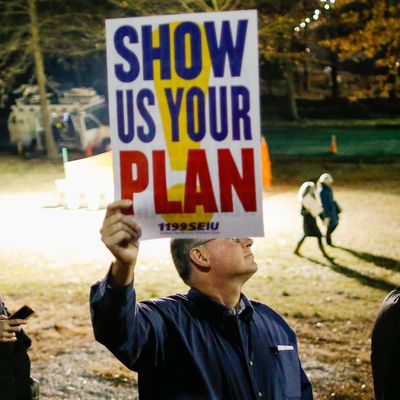

Republicans may not have even realized until recently how deeply their ability to make political hay on Obamacare depended on not having power. They could posture against every inconvenient aspect of an industry nobody has ever liked, and promise all things to all people, with no responsibility to fulfill their grandiose promises. Now the dynamic has reversed. Loss aversion has inspired massive, energetic protests to speak up for a law Democrats could hardly be roused to defend before, while the energy has drained away from the opposition. Amazingly, polling for Obamacare, which has been unpopular since the outset, has sharply reversed. The last ten polls all show net positive approval for the Affordable Care Act. If Republicans somehow muster the partisan discipline to tear down Obamacare, as opposed to settling for minor changes, they will have to be willing to endure searing political pain.

And this is all happening before Republicans have published a detailed plan. That is the most amazing aspect of all. Obamacare repeal faces dire peril, and the most painful steps have yet to come.