A few weeks ago, I found myself in an eerily quiet Chinatown during the Lunar New Year. The police had blocked off entire blocks for crowds that never showed up. A few troupes of celebrants beat drums and carried paper dragons through empty streets. Restaurants that are reliably packed on a Saturday afternoon stood vacant and glum. At the time, it seemed like an aberration. This year’s plague, the novel coronavirus, was still largely confined to Wuhan, China, and the neighborhood’s abandonment felt like alarmism tinged with prejudice.

But the virus has finally arrived. And when, as seems likely, the latest superbug starts whipping around, borne from borough to borough by subway, sneeze, and the interconnectedness of all New Yorkers — we will collectively have to decide whether we to turn the city into an outsized version of that surreal day in Chinatown.

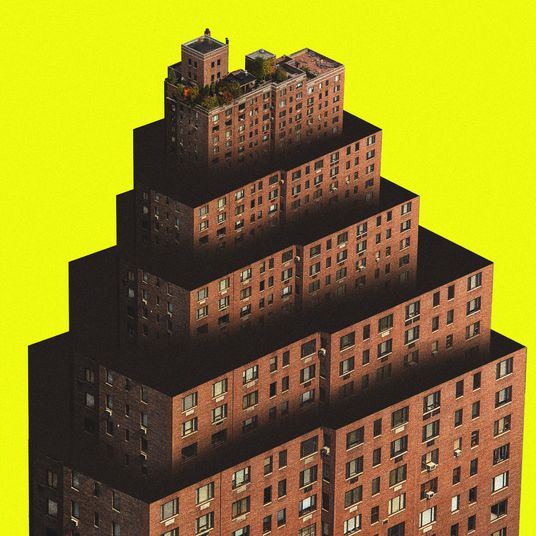

The virus feeds on proximity, and proximity defines the city. Call it energy, congestion, convenience, bustle, efficiency, claustrophobia, culture, or the anonymity of crowds — those qualities that make New York New York depend on large numbers of people huddling together. The virus — and the fear of the virus — threaten to do what terrorism and crime never could: clear the streets and turn us into 8.6 million misanthropic agoraphobes, unwilling to commute, eat out, and exercise our constitutional right to congregate.

We’ve been here before, within recent memory. SARS, Ebola, and swine flu blew through without bringing the city to its knees. “Infectious disease is a recurring theme in New York’s history, and so are panic and rumor,” says Sarah Henry, the deputy director of the Museum of the City of New York, who curated the 2018 exhibition “Germ City: Microbes and the Metropolis.”

The show opened with a regularly updated chart called “The Conquest of Pestilence,” which shows the change in overall death rates over 200 years. The 19th century was a time of horrifying spikes, when outbreaks of cholera, yellow fever, smallpox, and other infectious diseases roared through the population. Public health measures, like the opening of the Croton Aqueduct and the pasteurization of milk, slowly but dramatically brought the fluctuations under control. On that scale, the Spanish flu pandemic of 1918, terrible though it was, shows up as a modest blip. The World Trade Center attacks barely register.

But though the chart is objectively reassuring, it doesn’t measure the psychological impact of modest statistical aberrations. AIDS brutalized urban culture, transformed the art world, and changed sexual practices. When reliable information is scarce, irrationality, prejudice and fear spread faster than the disease. The desire to control a poorly understood threat often leads to scapegoating and violence that sometimes take bizarre turns. During the 1916 polio epidemic, a rumor blaming the outbreak on cats and dogs triggered the mass murder of household pets.

We’re all too young to remember what may be the most, um, germane, example of a new plague striking the modern city. In the fall of 1918, the influenza pandemic that was ravaging armies and continents hit the East Coast, killing tens of thousands in a few months, before abating — for a while. The flu came in lethal waves, which made relief deceptive. Some cities shut schools, stores, and theaters for months. New York’s health commissioner, Royal Copeland, insisted on keeping the city humming as normally as possible on the theory that with so many residents packed into airless tenements, they were safer out and about than at home. To relieve subway crowding at rush hour, businesses staggered their schedules.

It was impossible then and remains hard now to know how well those measures worked. Under attack, Copeland pointed out that the death rate in New York was significantly lower than in Boston and Baltimore, which had taken more stringent measures. On the other hand, a 2013 study suggests that, at least at first, children may have died in disproportionate numbers because they picked up the bug at school.

Ours is a radically different metropolis from Copeland’s. A century ago, even in non-pandemic conditions, population groups remained largely confined to their neighborhoods. Children walked to school and many piecework laborers commuted a few yards from their beds to their front rooms. Today’s New York is more populous, more mobile, and more enmeshed. Collectively, we take 1.7 billion subway rides a year, far more than in 1918. Many of us pack into elevators at least four times a day, from home to street, from street to desk, and back again, inches from our traveling companions. The city is Disneyland for germs.

Even for those who never get sick, it’s hard to fathom all the ways in which urbanites, caught between irrational denial and inchoate panic, will have to live against the grain, and how ill-suited we are to living apart.

If Copeland’s successors determine that partial measures aren’t enough — or if anxiety settles in — and a lockdown goes wide and lasts long — the city’s economy could start unraveling fast. As people stay off the subway, and even taxis carry a thin sheen of microbes, work life will go into hibernation. In the short term, that may be a good thing. Cruise ships have come to resemble floating skyscrapers; now office buildings might feel alarmingly like vertical cruise ships, with central ventilation systems poised to infect thousands with terrifying efficiency. Some employees can work from home, but store clerks, hotel maids, restaurant cooks, and teachers will suddenly have nobody to serve and no safe way to get to work, even if they hang on to their jobs. The affluent can try ordering takeout, but when the pizza guy shows up in a hazmat suit, it tends to dampen your appetite.

Doing without Broadway or theaters or live music may seem like a second-order form of suffering, but that’s only true for the audience. New York’s cultural life supports an army of actors, stagehands, musicians, ushers, tailors, publicists, and other support staff, few of whom will keep getting paid through a prolonged shutdown. In this apocalyptic scenario, the city empties of tourists, students, business travelers, and anyone with a car and a country house. All others will self-sequester and hope that Amazon has the power to coerce its employees to show up for work and keep the deliveries flowing. The global money whirl slows, local taxes dry up, and the city starts to crumple in on itself.

There’s a weird kind of beauty to the city when it goes suddenly dormant on Super Bowl Sunday and New Year’s Day, or during a blizzard. Traffic vanishes, the decibel level drops. Overnight, the fabric knits itself back together, though, and like a forest full of birds chirping again after a gunshot, the urban racket rises to its normal clamor. New York can absorb a few days, or even a couple of weeks of immobility. It has, after all, withstood obliterating fires, floods, war, crime waves, drug scourges, and terrorist attacks. The city is resilient enough that, a century later, even the 1918 flu is a vaguely recollected incident.

“New York is vulnerable,” says Henry. “It’s the densest, biggest city in the United States, with a tremendous churn of people coming and going. But we also have a robust and sophisticated public health infrastructure.” That’s what’s kept the pestilence at bay.

Still, a delinquent strand of genetic material and the terror it engenders can damage the contemporary metropolis in old, insidious ways. At this point, we know little about the virus’s timetable — how long it lingers, how often it returns. The list of what we don’t know about how we will react is even longer: at what point short-term accommodations become a way of life, when prudence edges over into despair, whether the city will somehow be exempt, or — more realistically — how quickly New York will once again become its raucous, crowded, gorgeously unlivable self.