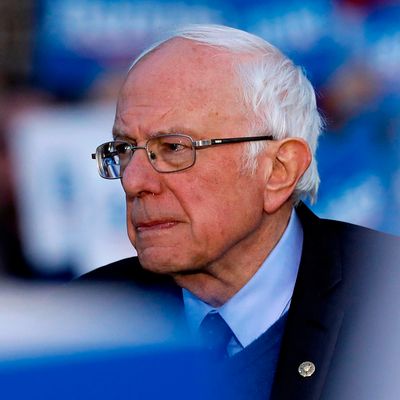

On the evening of March 10, no one was surprised that Mississippi and Missouri were called for Joe Biden about a minute after the polls closed. The much bigger news came a bit later, when Michigan was called for the former veep. This was the state that Bernie Sanders really, really needed to win, in part because it had been so key to his highly competitive race against Hillary Clinton in 2016. Indeed, when polls showed Biden comfortably ahead in Michigan, some observers discounted them because polls had also showed Clinton waxing Bernie. In addition, Sanders and his campaign really kicked out the jams there, concentrating their resources in hopes of replicating the 2016 result.

But it wasn’t to be. With nearly two-thirds of the vote in, Biden was leading Sanders by a hefty 13 points (Bernie beat Clinton in Michigan by one-and-a-half points four years ago).

In some respects, Sanders’s losing 2020 coalition was similar to his winning 2016 base of support, according to exit polls. He won under-30 voters by 77-19 this time around and by 81-19 against Clinton. These voters were, however, a somewhat smaller proportion of the primary electorate than before (16 percent as opposed to 19 percent in 2016). He won an identical 28 percent of black voters in both elections. He did slip from 30 percent to 23 percent among over-65 voters.

But the number that leaps off the page in the exit polls is that Biden defeated Sanders among non-college-educated white voters (a.k.a. the “white working class”) by a 50-45 margin, which contributed to a 52-42 advantage for Biden among white voters generally. Bernie famously won the white working-class vote in Michigan over Clinton by 57-42, and won white voters by 56-42. There’s been a furious debate since then as to whether some non-college-educated whites voted for Sanders on their way right out of the Democratic Party and into Trump’s GOP. That’s unclear, but these voters represented the same percentage of the 2020 primary electorate that they did in 2016, despite sharply higher turnout overall.

If Michigan does represent the beginning of the end of the Sanders campaign, it’s because the two demographic groups he could count on —under-30 voters and Latinos (which exit polls suggest he won 55-37) —weren’t big enough in enough places to overcome his weaknesses elsewhere. The consolidation by Biden of all those “elsewhere” voters produced the stunning turnaround of a race that it looked like Sanders was winning as recently as two weeks ago.