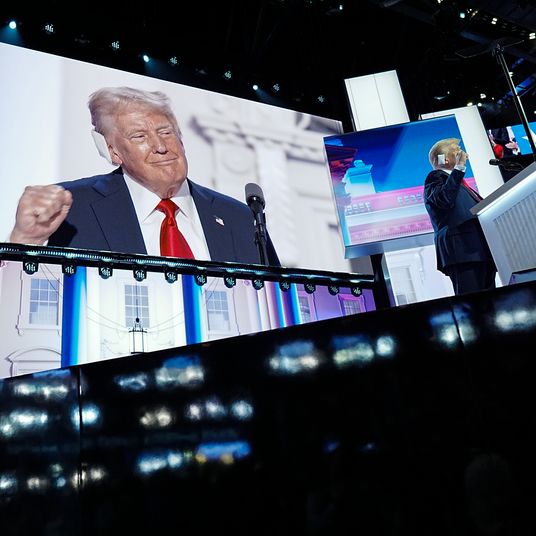

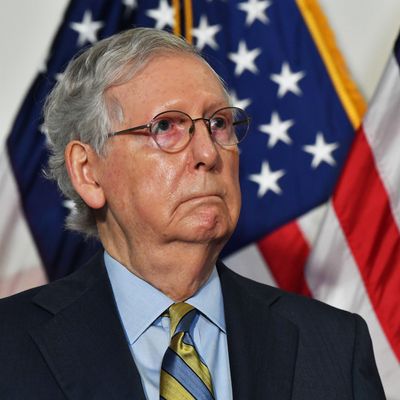

As Donald Trump’s odds of reelection steadily erode, Senate Republicans are pivoting to a new campaign strategy: promising voters that they will serve as a check on Joe Biden’s attempts to save the country from a depression.

Of course, Mitch McConnell’s caucus isn’t phrasing its new pitch in precisely these terms. But according to a new report from Bloomberg, one reason why Senate Republicans are opposed to a significant stimulus before Election Day is that they want to simultaneously (1) campaign as a check on a Biden administration and (2) establish credibility on the deficit, which they can subsequently use to stymie a future Democratic president’s efforts to rescue a flagging economy. As Bloomberg’s Steven Dennis and Jordan Fabian write:

Some senators are shifting their campaign pitches to position themselves as a brake on Biden and the Democratic agenda. North Carolina Senator Thom Tillis, who is trailing Democrat at Cal Cunningham, told Politico last week that a Republican Senate was “the best check on a Biden presidency.”

A GOP strategist who has been consulting with Senate campaigns said Republicans have been carefully laying the groundwork to restrain a Biden administration on federal spending and the budget deficit by talking up concerns about the price tag for another round of virus relief. The thinking, the strategist said, is that it would be very hard politically to agree on spending trillions more now and then in January suddenly embrace fiscal restraint.

As for the deficit: In August, the progressive polling firm Data for Progress (DFP) tested whether voters want Congress to prioritize COVID-19 relief over debt reduction, offering progressive and conservative talking points in favor of each imperative. By a 55 to 34 percent margin, voters favored stimulus:

One month later, DFP posed the question slightly differently, asking voters whether “the government needs to spend more to address the coronavirus pandemic, even if it means increasing the national debt and deficit,” or whether it has spent enough and should not “do anything else to increase the national debt and deficit,” or, finally, whether it has already spent “too much” and should “cut spending to reduce the national debt and deficit.” Put like this, support for more spending is overwhelming:

This consensus is likely to harden in the coming weeks. In the two months since the CARES Act’s unemployment benefits phased out, the pace of recovery has markedly slowed, while permanent job losses — as opposed to temporary, lockdown-induced furloughs — have steadily increased. Absent further congressional action, a conventional recession (which is to say, one driven by a self-perpetuating cycle of job losses and reductions in consumer spending) is likely to grow out of the remains of last spring’s unconventional downturn.

What’s more, unlike the 2009 stimulus, the CARES Act was sufficiently large to make the efficacy of the government simply giving people money unmistakeable. In April, at the height of America’s economic shutdown, U.S. households enjoyed record-high personal-income growth. In the midst of a recession, $1,200 relief checks, $600-a-week unemployment benefits, and robust central-bank support for asset markets allowed the typical American household’s financial condition to improve. This demonstration of Keynesianism’s validity was so broadly persuasive, the right-wing National Review published an editorial this week crediting the CARES Act for the fact that “personal incomes soared in the second quarter,” and calling on Republicans to support another recovery bill.

All of which is to say: To the extent that Senate Republicans plan to save their majority by pivoting to a “We’ll be a check on Biden” message, selling themselves specifically as a check on deficit-expanding economic relief is among the worst versions of this gambit they could possibly pursue. It’s an appeal that works as fan service to doctrinaire conservative activists and donors, not as a persuasion message for the median voter.

A second odd aspect of the GOP’s strategic thinking is the notion that supporting stimulus now will leave them with no standing to shriek “But the deficit!” next year, as a means of obstructing Biden’s agenda. Apparently, the many trillions of dollars they’ve already added to the national debt to finance Trump’s tax cuts, giant Pentagon budgets, and the CARES Act did nothing to tarnish the GOP’s credibility on the national debt — but passing another round of extremely popular emergency economic relief somehow would.

The Republican position here is roughly akin to that of a cannibal who gobbles up toddlers by the dozen each weekend, then dutifully observes “meatless Mondays,” so as to safeguard his credibility as a vegan.

It’s quite possible that Republicans will have no difficulty getting the mainstream media to take their deficit concerns seriously in 2021, irrespective of their fiscal profligacy while in power; this certainly has been the historical pattern. But if the Beltway press is still willing to credit GOP concerns about the deficit today, then passing an economic-relief package in response to a once-in-a-century emergency — with the Federal Reserve’s encouragement — will not stop that press from giving the party’s self-avowed deficit hawks the benefit of the doubt tomorrow.

In their paid messaging, vulnerable Republican senators evince a reality-based conception of the electorate’s preferences; Martha McSally, Steve Daines, and Joni Ernst are all airing ads in which they express their (fraudulent) support for guaranteeing affordable health insurance to people with preexisting conditions. But, by all appearances, the broader caucus has grown too insulated from popular pressure (as most represent deep-red states) and too credulous of their own propaganda to understand that “We will prevent Biden from sending you money in the middle of depression so as to keep the national debt at $23 trillion instead of $25 trillion” is not a popular platform.