This article was featured in One Great Story, New York’s reading recommendation newsletter. Sign up here to get it nightly.

In February 2024, dairy farmers in the northwest corner of the Texas Panhandle noticed that their herds were getting sick. A cow’s temperature would spike, and she would stop eating. Soon, her milk would dry up or turn thick — tests would reveal the milk had twice the normal number of white blood cells. The feverish cows would barely drink any water. As they grew dehydrated, their eyes sank into their heads. Nearly all of them had mastitis: a swollen, painful udder and teats, which made milking difficult.

The disease seemed to be spreading; veterinarians in the region heard from colleagues in Kansas and New Mexico who reported the same constellation of symptoms. On March 14, a group of them got on a conference call with animal-health specialists from around the country, trading information on what they had begun calling “mystery cow disease.” “We made a master list of causes and just started checking it twice,” said Barb Petersen, a veterinarian who cares for 40,000 cows on several dairies near Amarillo. Was it heavy metals in the feed? That could explain why so many herds had gotten sick so quickly. But no, the feed was okay. A bacterial infection? A coronavirus? Every test they ran came back negative. Whatever this was, it wasn’t something any of them had seen in cows before.

In This Issue

Around the same time, some of the farmworkers Petersen saw on her rounds started to fall ill. Most had conjunctivitis, or pink eye, but some developed fevers bad enough to keep them home from work. “We felt like, Gosh, we don’t think this is a coincidence,” Petersen said. “We’ve got to get to the bottom of this.”

Petersen, 41, has the calm forthrightness you might expect in someone used to working with large animals. She spends most of her days on the road, traveling from dairy to dairy. During the early part of the outbreak, she was as busy as she’s ever been: fielding calls from farmers, coordinating lab tests, and tending to sick cows. She came home each day exhausted. “I’m taking off all my farm clothes in the garage,” she said. “I have animals at home, so I’m making sure I’m not trying to bring something home to them.”

A breakthrough came from Kay Russo, a veterinarian who had studied both dairy cows and poultry. Russo told Petersen that she’d been monitoring an outbreak of avian influenza that had spread from Europe to South America, where it had crossed over from birds into the sea-lion population, killing more than 20,000. Had Petersen noticed any dead birds at the dairies? She had. (“A shit ton of dead birds,” in Russo’s words.) Petersen gathered a few and sent them to a lab. The results came back positive for influenza-A subtype H5N1. Bird flu. With that diagnosis in mind, one of Russo’s colleagues tried to get some bovine samples tested for H5N1, but the lab refused. “They wouldn’t run it,” Russo said, “because it wasn’t on their list.” No cow had ever been infected with H5N1 before.

A few days later, Petersen got a call from one of the dairies. The cats on the farm had become seriously ill after drinking milk from the sick cows: Some had gone blind and lost control of their muscles, mucus streaming from their noses and eyes. Many of them died. When Petersen mentioned the cats to Drew Magstadt, her former classmate at Iowa State’s College of Veterinary Medicine, he remembered that neurologic disease was a well-documented symptom of influenza A in cats. He offered to test for the virus if Petersen would send samples to his lab at Iowa State. “Those cats were really the key to finding this out as quickly as we did,” Magstadt said.

At Magstadt’s request, Petersen gathered milk from eight infected cows into plastic tubes and collected the bodies of two dead cats, wrapping them in plastic bags. She shipped it all in a cooler to Magstadt’s lab, more than 600 miles away in Ames. “I don’t want anything leaking,” she said, “so everything was triple bagged. I don’t want anybody at FedEx or UPS getting a surprise.” The samples arrived the morning of March 21, a Thursday, and by that night they had their results: The cats were positive for influenza A, as was the milk. The next day, Magstadt determined via PCR that it was H5N1, and there was a lot of it, especially in the milk. “I was very, very surprised,” he said, “particularly at the amount of virus.”

Magstadt sent Petersen’s samples across town to a lab run by the U.S. Department of Agriculture, which formally confirmed the presence of H5N1, and the massive apparatus of the federal government began to whir into motion. Petersen was suddenly receiving calls from multiple federal agencies. “Normally, I’m not going to talk to people who are in Washington, D.C., on the weekend,” she said. The response to the outbreak had transformed into a political problem.

On the following Monday, March 25, the USDA announced that highly pathogenic avian influenza had been found on farms in Texas, Kansas, and New Mexico. The agency urged farmers to report illnesses, revealed plans for widespread testing and new biosecurity measures, and soon put restrictions on interstate transfers of dairy cows. There was hope, in those days, that the outbreak could be contained.

Now, a year later, the country is, in Russo’s words, “a pot of swirling virus with every species thrown in the middle.” Multiple strains of H5N1 are burning uncontrolled through cattle herds and poultry flocks in almost every region. Farmers have been forced to euthanize millions of chickens, turkeys, and ducks. Pet food made from infected meat has been linked to the deaths of multiple house cats, and the list of species testing positive for bird flu grows longer every day: squirrels and raccoons, dolphins and deer mice, polar bears and rats, skunks and alpacas. In November and December, at an animal sanctuary in Washington, 20 big cats died of the virus, including four cougars, four bobcats, and a tiger.

Most of the 70 human cases reported to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention have been mild. A bad case of pink eye, maybe a fever, then a full recovery. But in January, when authorities in Louisiana announced that a man had died after being exposed to sick and dead birds in his backyard flock, it seemed to signal an ominous turn. Of the 964 human cases of H5N1 reported to the World Health Organization since 2003, nearly 50 percent were fatal.

This was, and is, a crisis that seems to demand an overwhelming response. The longer we allow the virus to run rampant through animal populations, the greater our chances of disaster. Instead, we’ve had a replay of the first year of the COVID pandemic, overseen this time, until recently, by a Democratic president: Early detection gave way to months of confusion and inaction. Good guidance was circumvented or ignored. Each state had its own rules about how to handle an outbreak or whether to test for one in the first place. We are now approaching a moment when our final line of defense for both people and animals may be an effective vaccine — just as the most anti-vaccine administration in history has taken power.

Once again, we are running an experiment to see whether half-measures will be enough to defeat a virus that has proved shockingly successful at spreading around the world. For now, H5N1 remains primarily a threat to birds and cows and the people who raise them. But if that changes, one thing is undeniable: We aren’t prepared.

The drumbeat of frightening news coverage of the bird-flu outbreak over the past year has seemed to carry a contradiction. Each troubling development — each new animal death, each perplexing human case, such as a child in British Columbia who developed severe disease — has been reported alongside the same refrain: The CDC says that H5N1 poses a low risk to the public. How could the virus be everywhere but still, somehow, in the CDC’s estimation, not likely to cause a pandemic?

H5N1 is already a panzootic. It spreads easily among birds via their digestive tracts; everywhere an infected bird poops, a new host can be born. Although highly pathogenic H5N1 has been around since at least 1996, sometime in 2020 a newer, more transmissible version emerged in Europe or Central Asia. This strain, known by the unwieldy name H5N1 clade 2.3.4.4b, infected species H5N1 had never touched before, causing mass die-offs of seabirds and spreading rapidly beyond the virus’s original geographic range.

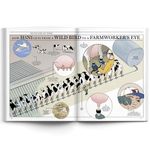

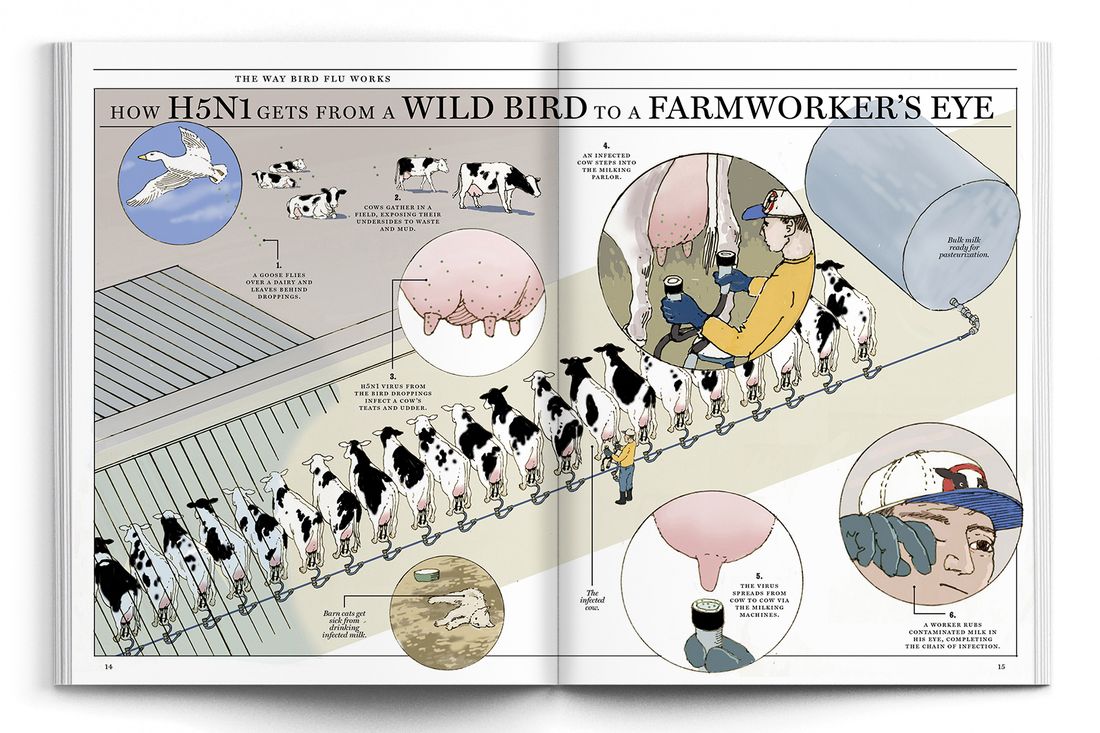

“It became quite clear early on that this was a completely different beast and that this was going to be potentially long term and not controllable,” said Martha Nelson, a computational biologist and the co-author of a recent paper about H5N1 in Nature. There were frequent crossovers into mammals but limited onward transmission until the first cows were infected — most likely when migrating birds left behind droppings on a dairy that got onto a cow’s udder. After that, spread was all but inevitable: Each cow stepping into the milking parlor could deposit virus on the automatic milker for the one that followed.

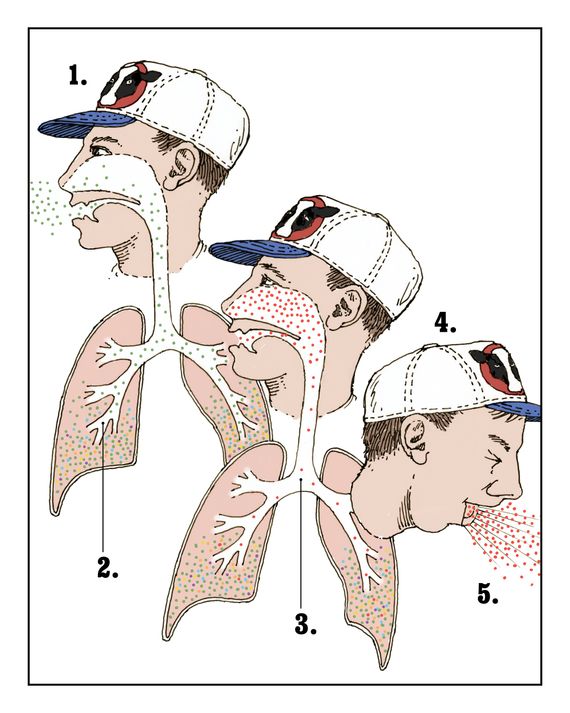

As transmissible as this virus was, it still didn’t have an easy way to infect humans. Smallpox, the 1918 flu virus, and SARS-CoV-2 could all bind to cells in our mouths, noses, and throats, which enabled rapid person-to-person transmission: Every breath, cough, and sneeze sent millions of virions into the air to be picked up by a neighbor. H5N1 can easily infect our eyes and the deep recesses of our lungs but, crucially, not our upper airways. Until that changes, the H5N1 pandemic will be held at bay.

The fact that the virus can infect a cow’s teat but not our nasal passages is a quirk of biology. Every virion has proteins on its surface — hemagglutinin, the H in H5N1 — that it uses to gain entry to a host’s cell. The hemagglutinin in H5N1 is excellent at binding to a particular cell-surface receptor that’s common in the digestive tract in birds, a cow’s mammary glands, and human eyes. We are lucky it’s not more widely distributed in our bodies. Cats, for example, have these receptors in places we don’t, which may explain why they have gotten sick from drinking raw milk from infected cows but humans haven’t. (Pasteurized milk is fine.)

Having won the influenza lottery with the placement of these receptors, we now seem determined to allow the virus to accumulate enough mutations to infect our upper airways after all. The virus has already made some progress in this direction. The strain found in Nevada’s dairy cows is better able to replicate in infected cells than the one that arrived from Europe. But for human-to-human transmission to take off, the hemagglutinin protein itself will have to change. First, it will have to switch its preferential binding from the kind of receptors in our eyes to their cousins in our upper airways. And then it will need to remain stable in low-pH environments; right now the protein degrades in our respiratory system because it’s too acidic.

To evolve, influenza is able to use a shortcut called reassortment, the same process that created H5N1 clade 2.3.4.4b in the first place. Rather than changing its genome nucleotide by nucleotide, it can swap whole segments of RNA with another virus. H5N1 could, for example, exchange its hemagglutinin for a version that binds easily to receptors in our noses by swapping an RNA segment with one of the two strains of flu already circulating in humans. But by its nature — borrowing material from viruses familiar to human immune systems — reassortment creates hybrids that our bodies are at least somewhat primed to fend off. A pandemic prefers naïve hosts, and reassortment robs it of that.

There is another path for mutations that is slower but could be more consequential. As the virus replicates within a host (a bird, a cow, a human), it’s constantly generating new versions of itself with slight tweaks to its genome — each, in the words of the German geneticist Richard Goldschmidt, a “hopeful monster,” an opportunistic mutant that voyages out in search of friendly tissue to infect. “The mutations are constantly occurring in cases of conjunctivitis,” said Michael Worobey, an evolutionary biologist who worked with Nelson on the paper in Nature. “But those mutants are in a desert, relatively speaking.” There’s no easy way for them to find new parts of the body to infect.

The virus won’t replicate into a desert indefinitely. In Worobey and Nelson’s paper, they write, somewhat cryptically, “The continued absence of H5N1 in U.S. swine is highly fortunate.” I asked Worobey to explain what that meant. Pigs, he said, “have both receptor types throughout their respiratory tract and therefore could conceivably be a much, much better place for the evolution of something that could become successful.”

Another place such mutations could take hold is in humans themselves. The H5N1-friendly receptors in our lungs are normally safe from infection unless someone deeply inhales large amounts of virus. (The few severe cases of H5N1 in the past year and the multiple deaths in the first outbreak among humans, in Hong Kong in 1997, may have been the result of people doing just that.) If a hopeful monster with the right kind of hemagglutinin was able to travel up the lungs and infect the upper airways — well, that’s the pandemic-ready virus we’re all worried about. The mutations may make it less deadly or more; we probably won’t know unless and until it happens.

“With this new reality we live in where cattle are infected and therefore dairy farmworkers are constantly being exposed,” Worobey said, “you have a situation with an H5 virus that is taking many more shots on goal to get into humans and get past whatever that last barrier is.” At this point, the most reassuring thing you can say is that the virus has been around for 30 years and hasn’t found a way to transmit effectively in humans yet. But Nelson warned against complacency: “My history of studying flu is that whenever you say influenza can’t do something, it does.”

For that reason, Worobey said he rejects the idea that H5N1 can be called low risk. “It seems a bit of a thumb on the scale to me,” he said. “I think the proper thing to appreciate is that we don’t really know the risk.” In the meantime, we’ve created a giant reservoir of novel virus in our dairy cows, 9 million little Wuhan wet markets (or, if you prefer, Wuhan Institutes of Virology) spread around the country, just waiting for the right occasion to spill over into the human population.

The Way Bird Flu Works

How H5N1 Gets From a Wild Bird to a Farmerworker’s Eye

When H5N1 began spreading in American cows, experts who have studied avian influenza all their lives looked on, horrified, as the country failed to get the outbreak under control. Worobey told me he talked to a veterinarian about transmission routes; he was accustomed to learning as much as he could about the animals that serve as the flu’s vectors. (Once, researching the origins of the 1918 pandemic, he investigated the Great Epizootic of 1872, which disabled millions of horses in North America; some blame the Great Boston Fire from that year on the lack of horses available to pull firefighting equipment.) “When you’re on a dairy farm,” he explained to me, “everyone carries a rag in their back pocket. You have to every few minutes wipe off piss, shit, milk, who knows. Getting into the eyes that way is easy and then the receptors there are ready and waiting.”

The official policy of the USDA is still elimination of H5N1, but making an environment like that biosecure is a formidable challenge: The central commodity of a dairy is teeming with virus — never mind the vulnerability of an open-sided barn or an unprotected field. In California, dairy farmers are required to report any positive tests, and infected herds are placed under quarantine for at least 60 days, at which point they have to test negative three weeks in a row. “I have quarantine authority,” Annette Jones, the state veterinarian, told me. “And I’m actually required by law to act. I can’t choose not to act.” The state has also required dairies to put strict limits on visitors and to institute various measures to control the spread of the virus from farm to farm, like disinfecting vehicles, clothes, and boots.

In Texas, the origin of the outbreak, many of these precautions are voluntary. Sid Miller, the state’s agriculture commissioner, took quick action after learning about the first cases. “We alerted everybody and quit transporting cattle out of state from that area,” he told me, “and we started changing some of our practices and put in better biohazard policies.” But he rejected the suggestion that the state should make some measures, like wearing goggles and disinfecting the milkers, mandatory for the dairies as well: “I mean, it’s in their best interest. They’re going to do it anyway. They don’t need a rule.”

The USDA has a national program for testing milk, but not every state is enrolled, and it didn’t begin until ten months into the outbreak. “Probably close to half of the known cases are in California,” William Hanage, a professor of epidemiology at Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health, told me. “And that’s not because California is bad. That’s because California is looking.” The result is an information ecosystem that’s familiar from the COVID pandemic, with the states reprising the roles they played in 2020.

The mildness of the disease in cows skews the incentives for individual farmers to take action. Most cows recover from the illness, albeit sometimes with diminished milk production. (Many of the early deaths in California, where “down cows” and stillbirths were relatively common, have been ascribed to high heat in the Central Valley just as the outbreak began.) “It’s not that big a threat,” Miller told me. “I mean, it’s like they had a cold for a week or the flu for a week, basically. It’s a devastating disease in poultry, but it’s a minor setback in the dairy business.”

The dairy industry, meanwhile, is broadly suspicious of government efforts to intervene. This is especially true of the CDC’s attempts to test and trace infected workers. The many thousands of undocumented immigrants working on farms, Hanage said, “are not going to be excited when the federal government is sending someone there to collect samples.” Trust in public-health officials in rural areas, already low, has eroded even more since 2020. Mark McAfee, the founder of Raw Farm outside Fresno, said the official number of infected farmworkers to date is probably an undercount: “I imagine a lot of farmers just don’t want to hassle with the paperwork and have the CDC go test them. It becomes a hassle factor. Most farmers don’t like hassle.” He pointed out that during COVID, the states doing a lot of testing and the states doing very little fared about the same. (This was basically true, at least until vaccines were widely available.)

The USDA provides emergency assistance for farmers with cows in quarantine, but some may prefer not to test in the first place. Beef and dairy exports are worth $19 billion a year, poultry exports another $5 billion. A positive test could jeopardize a farmer’s ability to ship products abroad. It’s notable that after a year of H5N1 spreading among cows, no beef herds have officially tested positive. But Russo told me that’s not the full story. “There is testing to show that there is seroconversion in these cattle, which would suggest they are getting infected with the virus,” she said. “That’s not been publicly released or seen the light of day. And I don’t know if it will.”

The USDA is asked to wear two hats, Petersen said: “They’re tasked with protecting animal health, but they’re also tasked with protecting the industry — and protecting the industry means defending trade.” According to the USDA, those two missions are not in conflict. “USDA’s priority is to protect American farmers and ranchers and their animals,” a spokesperson said, “which closely aligns with its mission to protect safe trade.”

The question of whether to vaccinate cows and poultry is even more fraught. H5N1 vaccines for cows are still in development, but the push to inoculate them will probably remain weak unless herds start developing more severe symptoms. (There were early reports of “long bird flu” in cows but no definitive evidence that it’s a widespread problem.)

Vaccines for poultry are already available, but trade complicates that decision as well. In 2023, France decided to start vaccinating its ducks — an effort, in part, to protect the national supply of foie gras. Within days, the U.S. banned all poultry imports from the country, and the embargo lasted for more than a year. The stated reason was to keep avian influenza out; vaccinated ducks, the reasoning went, could be asymptomatic carriers of the disease. If the U.S. began vaccinating its poultry, it could expect similar bans from other countries. Brooke Rollins, the secretary of the USDA, recently announced the department would devote $1 billion to fighting avian influenza, including up to $100 million for vaccine research, but declined to authorize the use of existing H5N1 vaccines for poultry. Until our trade agreements are renegotiated, that authorization likely won’t arrive.

The poultry and dairy industries seem to be on a collision course. Once a herd recovers, it has some immunity against future infections. The same isn’t true for chickens, ducks, and turkeys. The virus can kill nearly all of those infected, but it rarely has a chance to get that far. As soon as the disease is detected, farmers are usually required to destroy the entire flock — commercial operations lost more than 50 million birds last year. And with no vaccine and no acquired immunity, the next generation of hatchlings will be just as susceptible to the virus as the birds they replaced.

Dairies and chicken farms are often neighbors, and they can share personnel, a steady source of potential new infections. With the amount of virus circulating, even stringent biosecurity — workers in protective suits, barns sealed off, active disease surveillance — hasn’t always been enough. Egg producers have been the hardest hit. “We’re going to have to do something for these poultry operations so that we can have eggs in this country, to put it bluntly,” Russo said. “Politics and trade and economics have been put before the health of animals, of humans, of science. And now we’ve got a real fucking mess on our hands.”

If H5N1 were to adapt to transmit readily among humans, our welfare would be, ultimately, in the hands of Robert F. Kennedy Jr., the secretary of the Department of Health and Human Services. Kennedy is skeptical of the epidemiological tools used to control viruses: testing, distancing, masking, and, especially, vaccines. His stance on the childhood vaccination schedule and the COVID vaccines developed under Operation Warp Speed — which he called “the deadliest vaccine ever made” — is well known.

He speaks less often about flu inoculations, which are administered annually to around 150 million Americans. But during a podcast in 2021, he revealed that he blamed the flu shot for the problems he’s had with his voice. “In 1996, when I was 42 years old, I got this disease called spasmodic dysphonia,” he said. “I had a very, very strong voice prior to 1996. Unusually strong.” He didn’t connect his disease with the vaccine until he found his condition on a list of possible side effects. The shot, he said, was “definitely a potential cause of what I’ve got, and I haven’t been able to figure out any other cause.”

Since Kennedy took over at HHS, the CDC has ended an ad campaign urging Americans to get the flu shot (its doomed slogan was “Wild to Mild”) and postponed the February meeting of the agency’s vaccine advisory group. At the end of February, members of the Food and Drug Administration’s Vaccines and Related Biological Products Advisory Committee learned that their March meeting, during which they were meant to determine the strains to be targeted by next year’s flu shot, had been canceled as well.

“I think that the administration, and most specifically Robert F. Kennedy Jr., is not interested in external expertise,” said Paul Offit, an infectious-diseases specialist at Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia, who has been a member of the FDA committee since 2017. “The man does not believe in the germ theory of infectious diseases.” Offit laughed despondently. “I dunno. I would have thought that was a minimum criteria for being the head of HHS, but what do I know?” (Kennedy did not reply to requests for comment.)

The federal government has spent years preparing for an avian-influenza pandemic. Dawn O’Connell, the former head of the Administration for Strategic Preparedness and Response, who left her job at the end of the Biden administration, told me that even before the virus began spreading in cows, ASPR and the CDC had been working with vaccine manufacturers to create a library of possible H5N1 vaccines that could be directed to different variants. “Because we had some of that library in place already,” she said, “we’ve been able to find a fairly well-matched vaccine” — one targeted to the strains in circulation — “that we’ve increased manufacturing for.” The Biden administration also invested $766 million in the development of mRNA vaccines for pandemic flu. “If the strain changes,” O’Connell said, “we would want to stay ahead of what’s currently circulating, and mRNA lets you do that a little easier.”

When O’Connell and I spoke in early January, there were 8 million doses of the H5N1 vaccine in the federal government’s stockpiles, with plans to add 2 million more by March. Several public-health experts I spoke to were frustrated that the Biden administration never released those doses to vaccinate farmworkers. Now it’s unclear if the federal government will ever release them. Last summer, Kennedy said that “there is no evidence these vaccines will work, and they appear to be dangerous.”

During the first Trump administration, when Alex Azar had Kennedy’s job, he said, “The secretary of HHS has a shocking amount of power by the stroke of a pen.” We may be about to find out how true that statement is. Offit thinks it’s likely that Kennedy will either eliminate committees like his — cutting off one path for dissent — or fill them with like-minded people. He could hold up the approval of new vaccines and refer existing ones for additional study. There may be few checks on his ability to do so. “In a normal world, you would have people at the FDA and CDC who would say, ‘No, sorry, that’s not going to happen,’” Offit said. “But we don’t live in that world. We live in a world full of sycophants who are just there to rubber stamp whatever it is they’re told to do.” It turns out that not interfering with the vaccine-approval process is another one of those norms that, like not renaming the Gulf of Mexico, we have scant ability to enforce.

We can predict the cascade of effects if the FDA withheld approval from an H5N1 vaccine. Without an FDA license, insurance companies won’t cover it. Without the market promised by insurance coverage, drug companies won’t manufacture the doses. It’s not a system that works without the support of the federal government.

In recent weeks, more than 5,000 employees at HHS have been laid off by Elon Musk’s Department of Government Efficiency. DOGE also fired 400 employees of the USDA’s Animal and Plant Health Inspection Service, which has been running the response to the H5N1 outbreak, including 55 associated with the lab in Ames that helped diagnose the first cases of H5N1 in the Texas Panhandle. Some of these employees were rehired, and the USDA wrote in a statement that “several job categories, including veterinarians, animal health technicians, and other emergency response personnel” at APHIS “have been exempted from the recent personnel actions.” But the turmoil in the executive branch continues. When I first wrote to Martha Nelson, the co-author of the paper in Nature about H5N1, she said she wouldn’t be able to talk with me because, as a staff scientist at the National Institutes of Health, she was subject to a blanket HHS communications pause.

O’Connell reminded me that, at the beginning of the COVID pandemic, federal officials had planned to use the strategic national stockpile, which is maintained by ASPR, to provide N95 masks to frontline workers. But the stockpile, they discovered, was empty. “They had not purchased PPE since H1N1,” she said, “ten years before.” Whatever missteps the Biden administration made regarding bird flu before its departure, we are undoubtedly on a better logistical footing than in 2020. As of January, the government had distributed 2.3 million pieces of PPE to farmworkers across the country, and it had accumulated 68 million doses of the antiviral medication Tamiflu.

If there ends up being scarcity this time around, it will have been by choice, a decision made by a weary public and the leaders they elected. Many Americans need time to rebuild their willingness to support pandemic-mitigating measures like lockdowns and masking. Some people need time to rebuild their trust in vaccines. “We may not even be able to have a serious conversation about it for a few years,” Hanage, the Harvard epidemiologist, said. “But viruses don’t look at our Google calendars to decide what they’re going to do.”

Kennedy got his job in part because a significant portion of the country thought that the government overstepped its authority during COVID, and that agencies like the FDA rushed the approval of vaccines for political reasons. Now that he is in charge of the public-health infrastructure of the U.S., we may get to see what the opposite approach would look like. Rather than a vaccine mandate, there may be a trade in gray-market vaccines acquired from abroad. Mitigation measures may be actively discouraged or penalized. As before, the rich may be able to protect themselves, but the poor will not. Kennedy and his critics rarely see eye to eye, but both sides would likely agree that, under his watch, we’re not going to see another Operation Warp Speed.

In February, one year after the initial outbreak, I went to visit a dairy to see how biosecurity had changed since H5N1 became a bovine disease. A second spillover from wild birds had recently hit cattle in Nevada. The general public, at least those of us prone to worrying, had begun keeping track of esoteric variant names again. This one was D1.1, a different genotype from the B3.13 variant already circulating widely. Nothing changed except the hope we’d have to eliminate H5N1 from the cow population only once.

I tried to find a suitable farm in California but was advised by Michael Payne, a researcher at UC Davis’s School of Veterinary Medicine, that all dairies he was aware of were now closed to nonessential visitors. In Pennsylvania, I found a farm with chickens and dairy cows offering tours, but a few days before the trip I got a call. All tours had been suspended until May. A few days later, the farm euthanized 2 million hens.

There were more options in Texas. After confirming a visit with one dairy, I asked Miller, the agriculture commissioner, what I should do to ensure I wasn’t helping spread the disease. “When you’re going from farm to farm,” he said, “disinfect your boots and your hands. Just use cowboy logic, basically.” I had neglected to get a flu shot this year, so I made an appointment at my local pharmacy. I wasn’t interested in being the Petri dish for any reassortment events.

The dairy was small by Texas standards. In a paddock near the entrance, a dozen or so calves, almost seven months old according to their ear tags, crowded near the steel fence as I approached. They were heartbreakingly cute. A few chickens walked around. A trio of ducks sat by a waste-covered pool. In the distance, the dry herd (cows given a break from lactation in the final months of their pregnancies) gathered under a tree. On other farms, it was 2020, but here it was still 2019.

In the milking parlor, one of the employees, a cheerful woman who had worked there for four years, demonstrated how the machines worked. The cows were led in through one door, workers attached four teat cups, and the milk was piped to a bulk tank before the cows were ushered out a second door. The room was about as clean as a cow conveyor belt could be. I asked whether they had made any changes to the operation over the past year, and the employee said they hadn’t. She told me the farm didn’t get that many wild birds passing through.

Earlier, a calf had licked my arms while I petted it, and I’d reminded myself the virus was concentrated in the cow’s mammary glands, not its mouth. Now the employee asked me if I wanted to try milking by hand. I declined, but another visitor stepped forward and followed instructions for coaxing the fluid down the udder and into the teat. A stream of milk hit the ground and splashed up into the air.

After spending weeks talking to veterinarians and infectious-disease experts about mastitis and quarantines and depopulation orders, it was jarring, and kind of wonderful, to be on a farm where the animals seemed healthy and the farmworkers happy. I did worry about their chickens and ducks. In an email, Martha Nelson drew a distinction between small farms like this one and the ones run by large conglomerates. “On a small farm, if you had an influenza virus spillover from birds to cows, it might have caused a small outbreak and then probably died out,” she wrote. Big operations were different, shipping animals, and potentially virus, all over the country.

Large farms with animals packed tightly together are excellent sites for rapid disease spread. That’s the story of the country’s egg producers. And one of the earliest examples of mammal-to-mammal transmission during the 2.3.4.4b outbreak in Europe occurred on a farm where nearly 52,000 minks were being raised for their fur. “Intensive farming is more likely to promote viral amplification,” Nelson and her co-authors wrote in Nature. This disease, like COVID before it, has a knack for exposing the flaws in our society: the brutality of factory farming, the vulnerability of undocumented workers, our mistrust of science and of one another.

After Barb Petersen helped solve the mystery of the outbreak in the panhandle, she spoke to the Associated Press and Bovine Veterinarian about what had happened. “My goal is that, hey, folks need to understand what’s happening. And the only way to do that is to tell your story,” she said. When the articles appeared, several clients cut ties with her. She said some of her colleagues lost business for taking farmworkers to get tested. “People are going through stages of grief,” she told me, “and some reactions that I got were anger and denial. Some of them were more severe than others.”

The future of this outbreak is still unknown. Rollins, the head of the USDA, has proved that she’s taking the problem seriously. And Trump recently named Gerald Parker, a veterinarian with experience bringing together public-health and agriculture interests, to run the Office of Pandemic Preparedness and Response Policy, a remarkably sane choice. The country’s animals will likely have access to a vaccine before its people do.

“When people ask me what worries me most,” said Hanage, “it’s very bluntly the fact that we don’t talk about what we will do when we actually see something really serious.” We may get lucky and H5N1 may never mutate to become pandemic-ready. But there are countless other viruses waiting to cross over, chasing us like Philip Larkin’s ship of death in “Next, Please”: “a black-sailed unfamiliar, towing at her back a huge and birdless silence.”

There’s no comfort in where we are. Our government has spent the past year allowing H5N1 to spread throughout the country and the past two months dismantling some of the best defenses we have against pathogens of all sorts. We’re beleaguered and suspicious and seemingly incapable of collective action for the common good. The only thing keeping us safe, for now, is the virus itself.