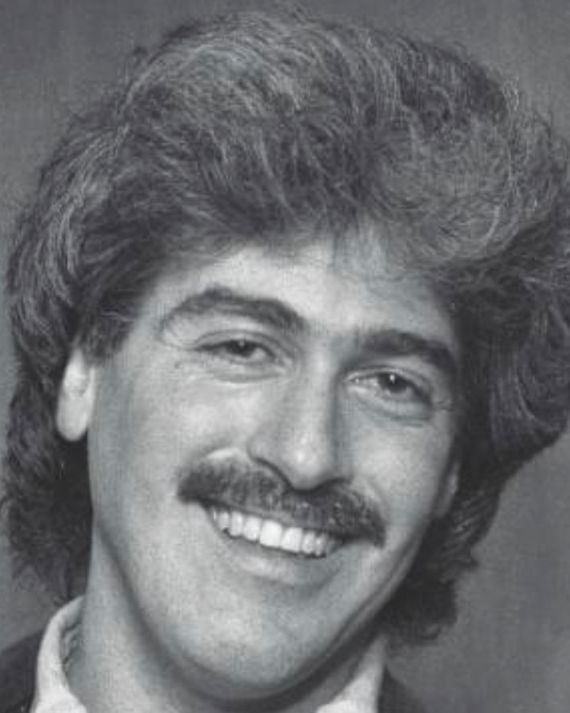

On a warm, misty January morning, Phil Mushnick is sitting in his Boca Raton townhouse where he now winters. He points out the herons in the lagoon near his back porch as well as an adjacent golf course, a thousand miles from his central Jersey home and Staten Island roots. “We were third-generation Staten Island Jews, a rarity,” Mushnick recalls. “I always say my ancestors came over on the ferry.” But amid his calm surroundings, the New York Post’s 72-year-old sports columnist is not exactly mellowing. He’s still triggered by the ills of America’s sports culture, still cranking out scathing critiques of blowhard announcers, badly behaving athletes, predatory gambling, and examples of hypocrisy. In his curmudgeonly “Equal Time” column, which he began writing in 1982, Mushnick recently blasted NFL commissioner Roger Goodell as “the enormously enriched say-anything/mean-anything Emperor of the Nero Fiddles League” and ESPN’s Stephen A. Smith for his “relentless cluelessness” and for being “the most transparently absurd sports presence on TV.”

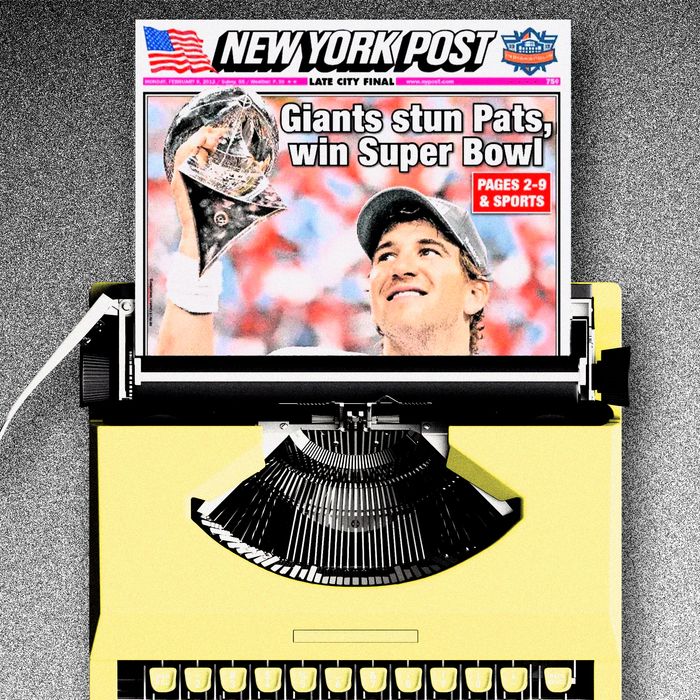

Along with 75-year-old Steve Serby and 74-year-old Larry Brooks, Mushnick is part of a holy trinity of snowy-haired sportswriters who anchor a section that trumpets itself as the “Best Sports in New York” — a claim that has gone virtually unchallenged since the New York Times shuttered its sports section and the Daily News, the Post’s fiercest competitor for decades, has been reduced to a skeleton operation. The paper covers the city’s sports scene like it’s still 1985 while navigating a vastly changed sports-media landscape. Locker rooms are now filled with what former Times columnist George Vecsey calls “the thumb people” — less-seasoned reporters constantly scrolling and tweeting updates. “It’s kind of interesting walking in there and seeing kids 50 years younger than me,” admits Brooks, who has been writing about the Rangers since the mid-1970s. Serby, who’s been covering the Jets and the Giants for over four decades, says, “Some of today’s athletes have no concept of what it means to be a reporter or columnist.”

Despite the game-changing advent of social media and personality-driven podcasts and YouTube opinion shows, the Post commands a formidable, loyal audience. “It’s the only game in town for a serious sports fan,” says longtime New York television journalist Tony Guida. “And it’s a very good game.” Amid the ongoing collapse of traditional print media, the Post has a daily circulation, digital and print, of more than 500,000, third nationwide behind the New York Times and The Wall Street Journal, and much of the tabloid’s success can be attributed to its robust sports section, almost a newspaper within a newspaper. “Those guys embody what the Post was and still is,” says Kevin Kernan, a former Post colleague who now writes for the baseball website BallNine. “They fiercely love what they do. They’re aggressive. Their knowledge and voice are still important.”

“Those three guys are institutions,” says former New York Giants general manager Ernie Accorsi, who began his career as a sportswriter and now lives in Hershey, Pennsylvania. “Growing up in the newspaper business, you read papers for the personalities. I hate all these paywalls but still read those guys.” It’s not only the older generation that appreciates them, suggesting something more timeless at work even as younger sports fans drift toward bite-size video clips and insta-reactions. As Alex Belth, an editor at Esquire and preservationist of pre-digital sports journalism, says, “You can also age really well in the eyes of Gen Z and millennials by just being your authentic self.”

In an industry ravaged by layoffs and early retirements, Brooks, Mushnick, and Serby are an endangered species — tab men from the old school. They joined the pre-Murdoch Post on pre-gentrified South Street in the early 1970s, when smoke-filled newsrooms bustled with brassy reporters amid clattering typewriters. They all grew up reading the Post’s superb sports section in the ’60s, which included the fearless irreverence of Larry Merchant, Vic Ziegel, Paul Zimmerman, Maury Allen, and Leonard Shecter, a chattering group dubbed “The Chipmunks” by the Post’s legendary postwar columnist Jimmy Cannon. It was Cannon who once mused, “A sportswriter is entombed in a prolonged boyhood.”

Steve Serby grew up in working-class North Massapequa as a shy, insecure teenager. He never drank a beer or went on a date in high school, and he dropped out of typing class because he couldn’t keep up; to this day he still types with one finger. His life trajectory changed when a teacher encouraged him to write for the school paper, and when an older student who attended Ohio University praised the journalism program there, Serby was sold. “The first time I was away from home,” he says. “I needed to grow up in the worst way.” He brought along his obsession with Joe Namath. “I idolized him and dressed in funky clothes I imagined Joe would’ve worn,” Serby says. “Even wore white shoes and grew a Fu Manchu.”

He became co–sports editor of the college paper (ironically also called The Post), making an impression with his groovy clothing and offbeat observations. On the infield of the Kentucky Derby, Serby wrote: “You’ll see all the weirdos of the Midwest bunched together like bananas.” “Steve was a creation of the era,” says Paul Hagen, one of the paper’s staffers, who went on to a prominent career covering Major League Baseball.

After he graduated, someone from the New York Post called Serby’s house in response to his job application, telling his mother there was an opening for a clerk. “He’ll take it!” she said. He ended up at the features department compiling TV and radio listings. One day Marv Albert, the “voice” of the Knicks and Rangers, called in to list his radio show’s guests. Serby happened to know Albert’s younger brother Al, who was Ohio’s hockey and lacrosse goalie. “Don’t you want to work in sports?” Marv asked. Serby replied with a version of “Yessss!” and the next day was sent to that section.

Larry Brooks grew up on West 79th Street, immersed in the city’s sports scene of the late 1950s and ’60s. He entered the prestigious Bronx High School of Math and Science at age 13 and was miserable. “I hated math and science, and most of my friends went to Stuyvesant,” he says. In 1964, he wrote a letter to several sportswriters, as well as renowned sportscaster Howard Cosell, asking them to weigh in on a raging issue of the day: TV’s impact on the sports industry. Cosell actually summoned him to meet, but Brooks’s bigger thrill was regularly going to Rangers games at the old Madison Square Garden on Eighth Avenue and 49th Street. The Blueshirts were bad in those days; when their goalie Gump Worsley was asked which team gave him the most trouble, he replied, “the Rangers.”

Still, Brooks was smitten by the punishing skill of the niche sport, which at the time was still composed of Original Six teams. After graduating from City College, he got hired as a clerk by the Post in 1975. He took dictation from veteran reporters, then soon became a fixture in press boxes; early assignments included covering the Bronx Zoo Yankees and the Ooh-La-La Rangers of the late ’70s.

Phil Mushnick grew up in the Sunnyside neighborhood of Staten Island, just down the hill from Wagner College. He admits being a miscreant: “a terrible kid, a total fuckup.” His mother died when he was young and his father, an insurance man and former Navy lieutenant in World War II, had little patience for his son’s lying and troublemaking and occasionally smacked him. “I deserved it,” Mushnick says. “In fact, it probably wasn’t enough.”

Mushnick found discipline and purpose in a prep school and small Waynesburg College in southwestern Pennsylvania. He joined the Post in 1973 as a copy boy making $80 a week. One day an editor asked if anyone knew anything about soccer, and Mushnick fibbed that he did. Next thing he knew he was covering the Pele-led New York Cosmos, a wild era in which Mick Jagger would seek out Mushnick to talk soccer after games. In 1981, Mushnick’s no-holds-barred reporting provoked a Dutch player named Wim Rijsbergen to strike him in the jaw on a team bus, which ended the practice of players traveling with reporters.

Impish and tireless, Serby rapidly rose through the ranks at a newspaper that he said “resembled The Front Page,” the classic movie about the misadventures of big-city reporters. In 1981, Serby became a legendary part of the Post’s back page. He had written critically about Jets quarterback Richard Todd, who was so irate that he refused to speak to him. “About a month later,” Serby recalls, “I wrote another column and the Post’s headline was, ‘With Todd at Helm, Jets Will Never Win a Super Bowl.’” (In fairness, the same could be said of dozens of subsequent Jets quarterbacks). Yet Serby says, “I think that story sent Todd over the edge.” Before a practice one day, the quarterback grabbed Serby’s neck and smashed him into the locker. He blacked out, and photographer Bob Olen took a picture of him with a bandaged nose that appeared the next day with the headline, “Todd Assaults Our Man.”

Serby was sidelined for two weeks as the Post pursued charges against Todd (he was ultimately fined $1,500 by the league). It was a national story, and a debate ensued on that Sunday’s NBC broadcast between Bob Costas, who defended Serby, and analyst Bob Trumpy, who sided with Todd. “It was surreal,” says Serby, who watched the exchange from his Bayside apartment.

Over the course of his 50-plus-year career, Serby has probably been the most familiar face of the section. His mantra is that he writes for the fans. “I serve four masters — my God, my boss, Rupert Murdoch, my wife (my third, but who’s counting?) and you,” he wrote in 2006.

He once wrote a cheeky gambling column titled “Mr. Loser,” and he has conducted over 1,000 interviews with sports figures and other personalities for his popular “Sundays with Serby” Q&A, beginning with a Giants rookie named Eli Manning in 2004. Serby can be hokey (“Don’t bet against Greatlin Clark”), but his sardonic coverage, especially of so many Jets failings — “He will be, now and possibly forever, The Butt of Jokes,” he wrote of quarterback Mark Sanchez’s infamous 2012 “butt fumble” — has long resonated with readers. “I wanted to be Steve Serby,” says Mike Vaccaro, the Post’s main sports columnist, while he was a kid growing up on Long Island.

Like his brethren, Larry Brooks is no stranger to scrapes. In 1977, when he asked Carlos May of the Yankees if he believed owner George Steinbrenner was making out the team’s lineup, May exploded: “Get the fuck out of my face!” A year earlier, he and colleague Jim O’Brien were covering an Islanders-Rangers game in which rookie Don Murdoch scored four goals. When Brooks asked O’Brien if he could get him a couple of quotes on Murdoch from the Islanders’ locker room, O’Brien retorted, “Do it yourself, you 90-day wonder.” They got into a fistfight, until Islanders coach Al Arbour ran out of his office to pull Brooks away. Brooks was certain he was getting fired. He got a call the next day from assistant sports editor Sid Friedlander. “Larry,” he said, “please don’t punch anyone again.”

After a decade doing PR for the New Jersey Devils in the 1980s, he rejoined the Post with his weekly NHL column “Slap Shots,” breaking big stories like Wayne Gretzky coming to the Rangers. He gave Henrik Lundqvist, then a rookie, his lasting nickname, the King. And he offered blunt opinions that earned him tirades from the likes of former Rangers coach John Tortorella and former defenseman Dan Boyle. Few have the institutional memory of “Brooksie,” who was inducted into the Hockey Hall of Fame seven years ago for excellence in hockey journalism. Last December, during a brutal stretch when the Rangers lost 13 of 17 games, Brooks — noting he’s been “watching the Rangers for nearly 70 years” — said he’d never seen anything this awful. “The Rangers have quit on their coach, they have quit on the organization, they have quit on themselves, they have quit on each other, they have quit on the fans who pay top dollar to fill the Garden and they have quit on New York.” (The Rangers’ official slogan is No Quit in New York).

Brooks was about to call it a career five years ago after losing his wife, Janis, to cancer. That changed with the arrival of an eager UMass intern named Mollie Walker, who had grown up in New Jersey devouring the Post sports section and would eventually be promoted to Rangers beat writer at age 23. She remembers excitedly gabbing about hockey to a decidedly reserved Brooks at a Rangers practice. But he was ultimately taken by her enthusiasm and determination. “She invigorated my career,” says Brooks. For Walker, the grandfather of two has been a godsend for her own budding career. “Imagine having your mentor and best friend wrapped up in one,” says Walker, who now co-hosts a Post podcast with Brooks called Up in the Blue Seats. “I’ve learned so much from Larry: how to stand up for yourself, how to be respected in the hockey space. I think the world of him.”

During his half-century at the Post, Phil Mushnick transformed the column on sports television and radio into a provocative forum of his wide-ranging outrage. “For better or worse, I’m paid to give my opinion — and I think everyone’s entitled to it,” he deadpans. Mushnick often dives into racially sensitive issues, and his grumpy diatribes are familiar: baseball players who don’t run hard, college and pro teams supposedly adopting gang-favored colors, excessive promotion of sports gambling, and announcers who holler too much. He skewers what he perceives as pretension and hypocrisy, going after John Sterling, Stephen A. Smith, Roger Goodell, and Mike Francesa almost on a loop. And he chronically reminds readers of the unfairness of ESPN firing tennis announcer Doug Adler in 2017 for describing Serena Williams’s aggressive play as having a “guerilla effect,” not “gorilla.”

In 1990, Mushnick infamously sparked national debate when he blasted Nike, Spike Lee, and Michael Jordan for exploiting inner-city Black kids by selling expensive Air Jordans. Mushnick blamed them for being the source of sportswear muggings and murder; Lee accused Mushnick of “thinly veiled racism.”

Mushnick says the Post has always had his back. “I’ve worked for six ownerships, and nobody’s ever told me what I can and cannot write,” he says. “And I’ve ripped the hell out of Fox, which as you know is run by Murdoch.” In the late 1980s, Donald Trump, then believed to be an adviser to Mike Tyson, excoriated Mushnick for his columns (as well as Mushnick’s appearance) in a letter that the Post refused to publish. Despite the bad blood, Mushnick called Trump years later pleading for him to not get involved with Vince McMahon, the professional-wrestling mogul who had filed suits against Mushnick for reporting on rampant steroid use and other WWE scandals. To this day, Mushnick regards McMahon as “a sociopath,” and pro-wrestling fans regard Mushnick as the worst kind of heel.

Despite the fact that their careers collectively span 150 years at the Post, none of them has plans to quit. “As my old editor Ike Gellis said, ‘You don’t retire, you expire,’” says Mushnick. Serby says, “I wouldn’t change my life for anyone.” And though they may seem like anachronisms in today’s information environment, they have shown, by putting their personalities first and never forsaking their credibility, that they are forefathers of new sports media. “I think I have a tabloid mentality in a digital world,” says Brooks.