Earlier this week, the U.S. Supreme Court declined an opportunity to settle a constitutional challenge to all-male military draft registration in the case of National Coalition of Men v. Selective Service System. It’s unclear whether all the justices concurred, but three of them (Sonia Sotomayor, Stephen Breyer, and Brett Kavanaugh) issued an explanation of the ruling, essentially deferring to Congress (as the Biden administration encouraged the Court to do) in determining the future of draft registration generally.

The case came to the Supreme Court because a federal trial court judge ruled the male-only draft unconstitutional, since the 1981 Supreme Court decision upholding exclusion of women was written at a time when combat assignments were closed to them. Since every assignment in all of the branches of the armed services are now open to women, the district court judge reasoned, the logic of the 1981 decision was moot. The Fifth Circuit Court of Appeals reversed the decision on the grounds that only the Supreme Court can reverse its own precedents. But it’s now squarely in the lap of Congress.

As Sotomayor noted in her statement, Congress authorized a commission in 2016 to examine the military draft, draft registration, and other forms of national service, and then make recommendations for statutory provisions. That commission issued its final report in March of last year. Among its many recommendations was this: “After extensive deliberations, the Commission ultimately decided that all Americans, men and women, should be required to register for Selective Service and be prepared to serve in the event a draft is enacted by Congress and the President.”

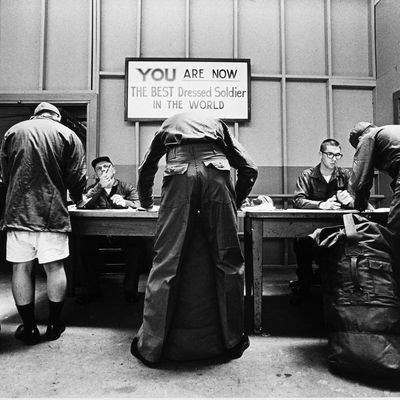

The wording of this recommendation reflects the reality that since 1973, when Congress allowed its Vietnam-era conscription powers to lapse, there has been draft registration without an actual draft (indeed, from 1975 until 1980, there was no registration, either, until Jimmy Carter restored it as Cold War tensions escalated). More recently, while the Selective Service System, which has administred the draft since 1940, has still required young men to register upon turning 18, and to remain eligible until the age of 26, most registrants haven’t bothered to update their addresses. So there would still have to be a pretty massive ramp-up of information before a draft could be resumed.

Naturally some lawmakers in Congress favor just junking the whole thing (Senator Ron Wyden has sponsored a Selective Service Repeal Act of 2021). But others, for various reasons, want to retain registration and then extend it to all 18-year olds, as the Commission on Military, National, and Public Service recommended.

Most 18-year-olds these days, and even their parents, can barely conceive of an active military draft. Only one percent of Americans served in the military during the past 20 years, despite those “forever wars” in Afghanistan and Iraq and U.S. military deployments around the world. But mass conscription was the norm during the Civil War and World War I, and for an uninterrupted period between 1940 until 1973. Up until its last few years, the draft was subject to regular criticism on grounds of unequal exposure to service and risk. County draft boards could be capricious (I had an uncle who obtained a 4-F exemption on medical grounds by eating several boxes of chocolate covered cherries the night before his physical and convincing the board’s backwoods doctor he was diabetic) and system-wide deferments for college students were bitterly opposed as creating a bias against working-class men.

In 1969, until the draft ended, the Selective Service System conducted a national lottery by date of birth to determine the order of conscription for men who had just registered. It was “fair” in the sense of being random, but didn’t seem fair to the poor schlubs born on the wrong day (my own lottery number, luckily, was 255 in a year when one-through-95 were the only numbers subject to conscription). Before the U.S. seriously considers a return to the draft, all the old questions of equity and efficiency will have to be revisited, along with the bigger question of whether it’s good for social solidarity, and even for peace, to expose a much larger percentage of the population to national service of some form. After all, in the era of the Founding Fathers, standing professional (or as many would have put it, mercenary) armies were considered an instrument of potential oppression, as opposed to citizen militias.

But however it shakes out, it’s very unlikely the United States will return to a military draft that excludes women. The draft was still barely hanging onto life when Phyllis Schlafly and her band of anti-feminists beat back the Equal Rights Amendment by arguing (among other things) that it would lead to women being dragged into military service. Turns out the ERA wasn’t necessary to make this aspect of equality likely.