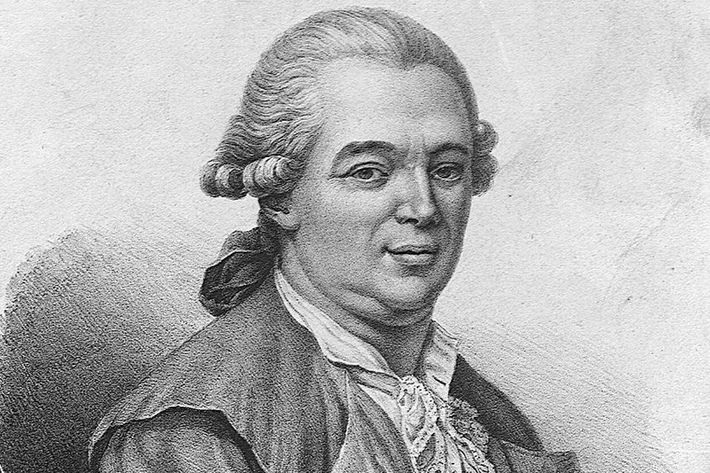

Considering its origin story, it’s not so surprising that hypnosis and serious medical science have often seemed at odds. The man typically credited with creating hypnosis, albeit in a rather primitive form, is Franz Mesmer, a doctor in 18th-century Vienna. (Mesmer, mesmerize. Get it?)

Mesmer developed a general theory of disease he called “animal magnetism,” which held that every living thing carries within it an internal magnetic force, in liquid form. Illness arises when this fluid becomes blocked, and can be cured if it can be coaxed to flow again, or so Mesmer’s thinking went. To get that fluid flowing, as science journalist Jo Marchant describes in her recent book, Cure, Mesmer “simply waved his hands to direct it through his patients’ bodies” — the origin of those melodramatic hand motions that stage hypnotists use today.”

After developing a substantial following — “mesmerism” became “the height of fashion” in late 1780s Paris, writes Marchant — Mesmer became the subject of what was essentially the world’s first clinical trial. King Louis XVI pulled together a team of the world’s top scientists, including Benjamin Franklin, who tested mesmerism and found its capacity to “cure” was, essentially, a placebo effect. “Not a shred of evidence exists for any fluid,” Franklin wrote. “The practice … is the art of increasing the imagination by degrees.”

Maybe so. But that doesn’t mean it doesn’t work.

More than 200 years later, research in neuroscience is confirming at least parts of Mesmer’s outlandish theory. No, there is not magnetic fluid coursing through our bodies. But the power of mere suggestion — of imagination, as Franklin phrased it — is a more effective treatment than many modern skeptics might expect, causing real, measurable changes in the body and brain. Hypnotism has been shown to be an effective treatment for psychological problems, like phobias and eating disorders, but the practice also helps people with physical problems, including pain — both acute and chronic — and some gastrointestinal diseases. Physicians and psychologists have observed this with their own eyes for decades; now, many of them say that brain-imaging studies (not to mention the deep respect people tend to have for all things prefixed by “neuro”) are helping them finally prove their point.

People who practice hypnotism in a clinical setting have long argued that the hypnotized patient enters an altered state of consciousness. Even if you’ve never undergone hypnotherapy, chances are you’ve experienced this state yourself. “It’s like getting so caught up in a good movie that you forget you’re watching a movie, and you enter the imagined world,” said Dr. David Spiegel, a psychiatrist and the medical director of Stanford University’s Center for Integrative Medicine.

In person, this looks strange enough. “There are a lot of ways to go into this state, but one way is to count to three,” Spiegel explains. “On one, you do one thing — look up. Two, two things — slowly close your eyes and take a deep breath. And three, three things — let the breath out, keep your eyes relaxed, and keep them closed. Let your body float. And then let one hand or the other float up in the air like a balloon.” When in this state, the hypnotized person’s hand will rise up into the air, as if on its own accord; Spiegel can reach over and gently pull the hand down, but it will float right back up again, as if it’s filled with helium.

In the brain, this state looks stranger still. A landmark study in the prestigious journal Science in the late 1990s, led by Pierre Rainville of the University of Montreal, described a study in which hypnotized people briefly placed their left hand in either painfully hot water, heated to 116 degrees Fahrenheit, or room-temperature water. Some of them had been told that they would be experiencing pain, but that they wouldn’t be very bothered by it — if, on a scale of one to ten, the hurt would normally register at an eight, they’d feel it as if it were a four. As all the participants placed their hands in the 116-degree water, their brains were scanned. The results were clear: Those who had been told that the pain would be less intense showed less activity in their brains — specifically, in the anterior cingulate cortex, which is associated with pain processing.

“That study changed the whole landscape,” said Dave Patterson, a psychologist at the University of Washington in Seattle, who has been using hypnosis since the 1980s to help burn victims withstand the intense pain that comes with the necessary but excruciating bandage removal and wound cleaning. Since the ’90s, other well-designed, controlled studies have been published showing similar changes in brain activity. In another slightly trippy example, researchers suggested to people in a hypnotic state that the vibrant primary colors found in paintings by Piet Mondrian were actually shades of gray. “Brain-scan results of these participants showed altered activity in fusiform regions involved in color processing,” notes psychologist Christian Jarrett.

“With hypnosis, you capture people’s attention. … You get people to turn to a more passive state of attention and to stop judging everything. To just let it happen,” Patterson said. “And when you do this, the amazing thing is that it’s as if you’re talking directly to the part of the brain that’s monitoring the reactions.” In his work, he ties suggestions of comfort to the daily practice of caring for burn wounds. “In burn care you know they’re going to pull off the bandages and then they’re going to start washing the wounds,” he explains. “The message is that when your wounds are washed, that will be the reminder of how comfortable you are.” The patient will often look like they’re asleep. “But if you ask them, ‘If you can still hear me, feel your head nod,’ almost always you’ll get that head nod,” he said. He’s seen this work for decades, but is so grateful for the recent advent of brain-imaging studies. They serve as evidence he can hold up to skeptics: See? Do you believe me now?

Not every person is hypnotizable to the same degree; some aren’t hypnotizable at all. “Hypnotizability … is modestly correlated with absorption, a personality construct reflecting a disposition to enter states of narrowed or expanded attention and a blurring of boundaries between oneself and the object of perception,” writes John F. Kihlstrom, a psychologist at the University of California, Berkeley, in a 2013 paper in Cortex. “Absorption, in turn, is related to ‘openness to experience,’ one of the ‘Big Five” dimensions of personality.”

But the reason why this ever works, for anyone, is still not clear. Some researchers argue that hypnosis may help us tap into “the autonomic nervous system to influence physical systems that aren’t usually under voluntary control,” Marchant writes in her book. She points to Karen Olness, a retired pediatrician and former member of the NIH Council for Complementary and Alternative Medicine, who has worked with children who could, through hypnosis, increase the temperature of their fingertips “way beyond what would be achieved merely from relaxation.”

Olness thinks there must be something about the intense mental imagery that comes with a hypnotic state. One little boy she worked with told her he was imagining that he was touching the sun. Whether such visions activate different parts of the brain than those associated with rational thought is less clear. As Olness says, “We’re a long way from specifics on that.”

We have, however, come a long way from the days of Mesmer’s animal magnetism. The increasing interest in mindfulness meditation suggests that mainstream acceptance of the mind-body connection is growing. This year, two well-received books by serious science journalists, Marchant’s Cure, out in January, and Erik Vance’s Suggestible You, out this month, explore this territory — the demonstrable results of hypnosis, faith, and even magic — long dismissed as pseudoscience or explained away as the placebo effect. Just last month, NPR reported that placebo pills work even when people know they’re taking a placebo. “Those are real, biological changes underlying those differences in your symptoms,” Marchant told Science of Us earlier this year. It’s all in your mind. But that doesn’t mean it’s not real.