Soon, millions of American families will come together to celebrate the holidays and passive-aggressively debate whether the country has just been saved or destroyed. For many, one annual ritual will provide a welcome distraction: watching a depressed child get berated and mocked relentlessly. A Charlie Brown Christmas, based on the “Peanuts” comic strip, has aired every December for the last 50 years — longer than any other holiday program besides Rudolph the Red-Nosed Reindeer. For last year’s anniversary, President Obama called the special “one of the country’s most beloved traditions.”

Lee Mendelson, who produced A Charlie Brown Christmas, thinks its message might be particularly relevant this year, with at least half the population feeling like someone pulled the football away. “These people identify with Charlie Brown maybe more than ever after this election season. He keeps fighting back and keeps enduring,” Mendelson says. “If we ever have to fight bullying, at so many levels, this is it.”

What most people don’t realize is that the holiday classic barely made it into production — and was almost buried forever. In 1965, no one believed that Charles Schulz’s story of an underdog sticking to his principles in the face of constant bullying would make for good TV. The show originally sprang from a failed documentary Mendelson had tried to make about Schulz. No networks had wanted it, but after Charlie Brown and the gang were featured on the cover of Time magazine, Coca-Cola’s ad agency, McCann Erickson, got the idea for a holiday special and approached Mendelson. Desperate after his documentary imploded, he lied and told the agent that, in fact, he and Schulz had discussed such a project. He called Schulz and told him they’d sold A Charlie Brown Christmas. “Schulz said, ‘What’s that?’” Mendelson recalls. “And I said, ‘It’s something you’re going to write tomorrow.’”

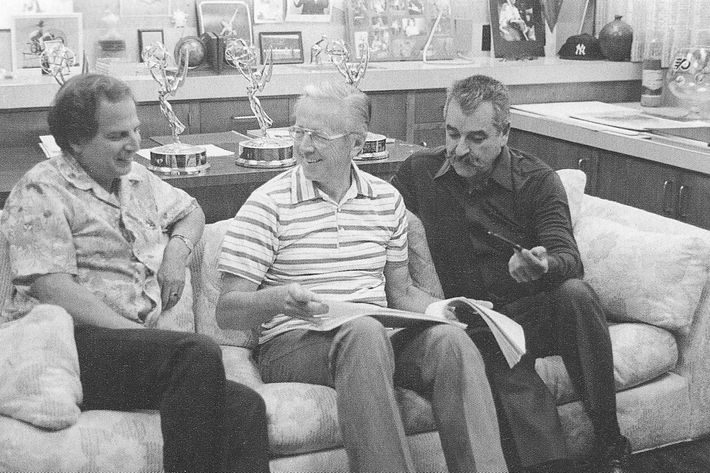

Mendelson rang animator Bill Melendez, who had helped animate a two-minute segment in the never-aired documentary. The three met in Schulz’s office in Sebastopol, California. Schulz wanted the show to focus on the childhood stress of putting on a Christmas play. Mendelson had just read The Fir-Tree by Hans Christian Andersen and suggested the story include a tree that is as sad and misunderstood as Charlie Brown. They cranked out an outline and put it in a Western Union shipment to Atlanta. Several days later, the agency told them they had a short six months to deliver the animated special.

Halfway through production, when the team was still working with black-and-white illustrations, a McCann executive (Mendelson is almost certain it was Neil Reagan, the older brother of President Ronald Reagan) showed up in Sebastopol to check in on the progress. He was put off by the slow pacing of the story. Mendelson, Melendez, and Schulz assured him it would be better once there was music and color. The executive said he wouldn’t tell the agency what he thought — because if he did, he was sure they would cancel the show.

For the music, the team had courted up-and-coming jazz musician Vince Guaraldi, whose “Cast Your Fate to the Wind” seemed to strike the same balance of somber enlightenment and childlike buoyancy that Schulz achieved in his comic. But when they played the introduction song as the children skated on the frozen pond, Mendelson realized it was way too slow and solemn. It was missing something. He sat down at his kitchen table and wrote out the words to “Christmas Time Is Here” on an envelope. Guaraldi enlisted the children’s choir of St. Paul’s Episcopal Church in San Rafael, California, to sing the lyrics.

Lyrics or not, the CBS executives didn’t think jazz belonged in a cartoon. They also challenged Schulz’s decision to use untrained children instead of professional adult voice actors. They especially couldn’t understand why children would use such big words. (Lucy: “We all know that Christmas is a big commercial racket. It’s run by a big Eastern syndicate, you know.” Charlie Brown: “Don’t think of it as dust. Think of it as maybe the soil of some great past civilization. Maybe the soil of ancient Babylon. It staggers the imagination. Maybe carrying soil that was trod upon by Solomon, or even Nebuchadnezzar.”) This, despite the fact that for about 15 years, “Peanuts” characters had spoken with advanced vocabularies.

Schulz even got pushback from his own team. Mendelson suggested a laugh track would save the show and Schulz responded by standing up and walking out of the room. When Schulz, a Sunday school teacher, said Linus should recite from the Gospel of Luke, Mendelson and Melendez protested. “We looked at each other and said, ‘Well, there goes our careers right down the drain,’” Mendelson recalls. “Nobody had ever animated anything from the Bible before, and we knew it probably wouldn’t work. We were flabbergasted by it.”

Of course, now Mendelson realizes that Linus’s segment probably made the entire project work. “That 10-year-old kid who recited that speech from the Bible was as good as any scene from Hamlet,” he says.

When CBS finally saw the finished product, they were sure it was doomed. It was still too slow, there was no action, the kids weren’t polished, the jazz didn’t belong. “The general reaction was one of disappointment — that it didn’t really translate as well as we thought it would,” former CBS executive Fred Silverman said in the 2015 short documentary, The Making of ‘A Charlie Brown Christmas.’ “There were specific negative comments about the music, the piano music, some of the voicing, which sounded kind of amateurish.”

But Coca-Cola had already bankrolled the program, and it was listed in TV guides. CBS had to air the show, but the execs were certain it would flop, never to run again. Mendelson thought he had killed Charlie Brown.

When A Charlie Brown Christmas aired at 7:30 p.m. ET on December 9, 1965, half of American TV viewers tuned in. The reviews were outstanding. Washington Post TV critic Lawrence Laurent wrote, “Good old Charlie Brown, a natural born loser … finally turned up a winner.”

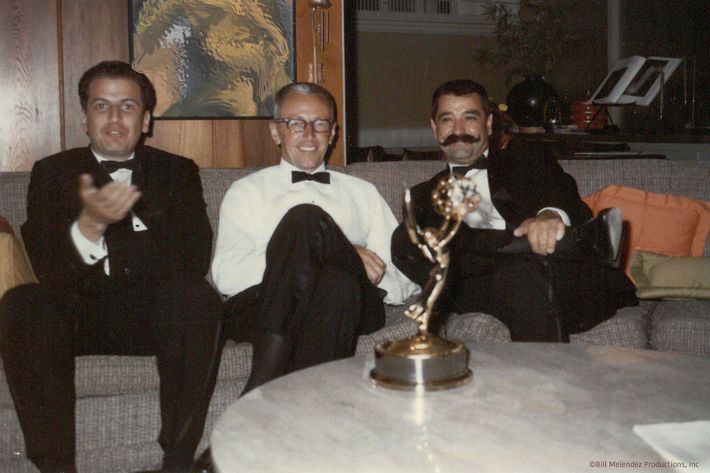

CBS immediately ordered four more specials. The show won a Peabody and an Emmy Award. In the end, Schulz, Mendelson, and Melendez wound up making about 50 “Peanuts” programs together, most of them for CBS. “We did whatever we wanted to do,” Mendelson says. “In our business, that’s craziness. We did one on cancer. We did one on war. We were just given a free ticket for half a century and tried to honor that by being entertaining but also being important and educational.”

The only person involved who wasn’t surprised was Schulz. The cartoonist was plagued by depression and self-doubt his entire life, but he always had confidence in his characters and their stories. He believed everyone knew what it felt like to fail despite doing everything right. “We hear about authors who write best about what they know. Steinbeck wrote about the West. Hemingway wrote about, well, everywhere,” says Mendelson. “Schulz jumped ahead in school so he was always the youngest, and he endured a lot of bullying. He felt a lot of loneliness, and I think that was the bedrock of his whole philosophy.”

Schulz’s message of perseverance in the face of dejection always resonated with American audiences, a reminder that we should keep kicking no matter how many times they pull the ball away. If that sentiment happens to be particularly relevant this year, Mendelson is pleased.

“Hopefully,” he says, “this positive program will be soothing at a time of uncertainty.”