Back in 2011, Jeopardy! aired a highly publicized “exhibition match” between its record-setting champions Ken Jennings and Brad Rutter and an IBM “question-answering machine” called Watson. Over a three-day period in February, millions of people watched as the supercomputer steadily triumphed over Jennings and Rutter, beating the men at complicated clues like “A recent best seller by Muriel Barbery is called this ’of the Hedgehog’?” (response: “What is Elegance?”) and “You just need a nap. You don’t have this sleep disorder that can make sufferers nod off while standing up” (response: “What is narcolepsy?”). Watson also made some funny mistakes, like when it responded “What Is Toronto?????” to a clue about the names of a city’s airports, while his human opponents correctly met the prompt with “What is Chicago?”

In the end, Watson racked up $77,147 to Jennings’s and Rutter’s respective $24,000 and $21,600; IBM was awarded $1 million to give to charity; Jennings jokingly welcomed “our new computer overlords”; and Jeopardy! got a ratings spike. At the time, IBM was estimated to have spent somewhere between $900 million and $1.8 billion developing Watson’s artificial-intelligence technology and, as far as the public could see, all the company had to show for it was an elaborate parlor trick.

“IBM has bragged to the media that Watson’s question-answering skills are good for more than annoying Alex Trebek,” wrote Jennings in a Slate piece about his encounter with the machine. “The company sees a future in which fields like medical diagnosis, business analytics, and tech support are automated by question-answering software like Watson.”

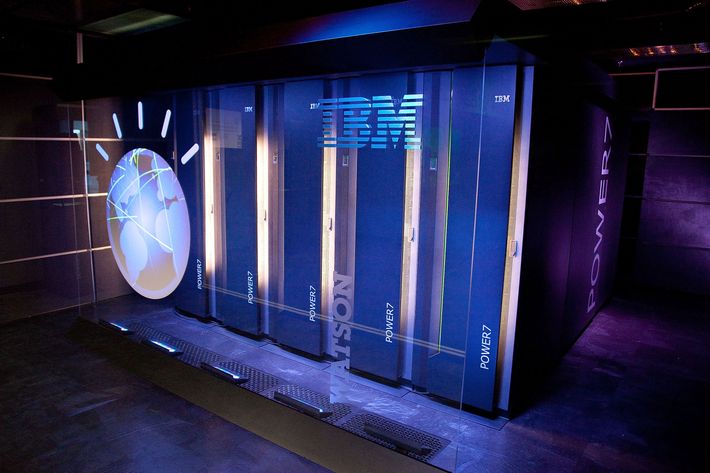

Five years later, that future appears to be knocking at the door. While Watson’s servers and memory have the capacity to process the entire American Library of Congress, the system, as IBM research head John Kelly put it to Charlie Rose on a recent 60 Minutes, “has no inherent intelligence as it starts. It’s essentially a child.” It took Watson, for example, five years to learn the information and human language required to play Jeopardy! As Rose explained, “Kelly’s team trained it on all of Wikipedia and thousands of newspapers and books. It worked by using machine-learning algorithms to find patterns in that massive amount of data and formed its own observations. When asked a question, Watson considered all the information and came up with an educated guess.”

Following the Jeopardy! gig, Watson was enlisted in all kinds of attempts at human endeavor. With help from the Institute of Culinary Education, it absorbed enough recipes and other food-related knowledge to generate a 231-page cookbook featuring “unusual ingredient combinations that man alone might never imagine.” (Reviews suggest that the recipes, while interesting, are often too complicated for the average home chef.) It assisted Hilton guests in the form of Connie, a robot that can answer verbal questions about the hotel’s amenities and local attractions. And it’s been used to answer customer inquiries via chat, email, and text for companies such as Nielsen and the Royal Bank of Canada. Unsurprisingly, the technology can sell stuff: Bear Naked Granola lets people use it to create absurdly specific mixes of nuts and oats, while the Watson-powered app Wine4.me helps unsophisticated drinkers find a bottle based on lay terms and vague flavor preferences. And last month, it even collaborated with producer Alex Da Kid, X Ambassadors, Elle King, and Wiz Khalifa on the song “Not Easy,” using what it learned from analyzing “New York Times front pages, Supreme Court rulings, Getty Museum statements, the most edited Wikipedia articles, popular movie synopses,” and the “tone” of blogs and tweets.

But it has also started fulfilling the more serious potential IBM promised, in the field of medicine. In the last few years, IBM has partnered with over a dozen of the United States’ top cancer centers, where employees have been “tutoring” Watson in oncology.

Watson is a very fast learner. Dr. Ned Sharpless, the cancer chief of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, said that he was initially wary of the technology. “Cancer’s tough business,” Sharpless said. “There’s a lot of false prophets and false promises. So I’m skeptical of almost any new idea in cancer. I just didn’t really understand what it would do.”

Sharpless came around when he saw how Watson could aid his patients by keeping up-to-date on research and treatment options in a way that is simply impossible for any human member of his team. “Understand we have 8,000 new research papers published every day. No one has time to read 8,000 papers a day. So we found that we were deciding on therapy based on information that was always, in some cases, 12 to 24 months out-of-date,” he said. But Watson was able to “read 25 million papers in about another week. And then, it also scanned the web for clinical trials open at other centers.”

In an analysis of 1,000 difficult patient cases put before Sharpless’s weekly molecular tumor board meeting, Watson made the same recommendations as its human counterparts 99 percent of the time. But what was even more exciting, he explained, is that in 30 percent of patients Watson found something new. “So that’s 300-plus people where Watson identified a treatment that a well-meaning, hardworking group of physicians hadn’t found.”

Researchers at the University of Texas’s MD Anderson Cancer Center have been similarly impressed. After months of processing data on the thousands of leukemia patients treated at the institute in the last several years, Watson began training. And as the Washington Post reports, there was a steep learning curve:

It sometimes had trouble telling whether the word “cold” in a doctor’s notes referred to the virus or the temperature. Or whether T2 was referring to a type of MRI scan or a stage of cancer. So each patient record had to be validated by a human.

Moreover, Watson’s recommendations were often a little wacky.

It sometimes had trouble telling whether the word “cold” in a doctor’s notes referred to the virus or the temperature. Or whether T2 was referring to a type of MRI scan or a stage of cancer. So each patient record had to be validated by a human.

“When we first started, he was like a little baby,” said Tapan M. Kadia, an assistant professor in the leukemia department. “You would put in a diagnosis, and he would return a random treatment.”

But after spending some time manually correcting Watson’s mistakes and giving it access to additional medical literature, the MD Anderson team gave it the title of “Oncology Expert Advisor” and put it to work. The results, according to one leukemia researcher, were “amazing.” “He beats me,” the doctor said. And Watson consistently surprises with novel ideas, according to another. “Oh my God, why didn’t I think of that?” said the researcher. “We don’t like to admit it, but it does happen.”

60 Minutes reports that IBM has now invested $15 billion in Watson and adjacent “data analytics technology,” which is also currently being tested on education and transportation projects. IBM insists that its goal is only to have Watson assist — as opposed to replace — the professionals in the fields where it’s being used. But if the technology does eventually live up to all of the company’s promises, it’s hard to see how it won’t fulfill Jennings’s 2011 prediction that “’Quiz show contestant’ won’t be the last job made redundant by Watson.”

“It’s only at a few percent of its potential,” IBM’s Kelly said. “I think this is a multi-decade journey that we’re on. And we’re only a few years into it.”